Library of Alexandria

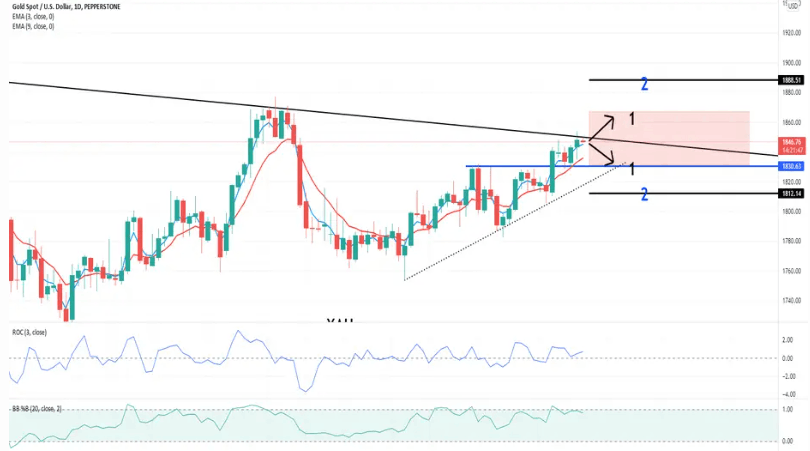

According to Arrhionos, Alexander the Great, Aristotle's most famous pupil, was the most famous student of Aristotle. When he stopped in the area between Lake Mareotis and the sea on one of his journeys, he said that it was 'a city'. 'the best possible place to build' and that this city would 'grow and prosper'. Looking somewhere far away from the temples of Olympus, he wrote that this new city would be dedicated to the Muses and Importantly, he ordered the construction of a library to bear his name. Alexander's successors in Egypt The first three Macedonian kings, fuelled by imperial ambition, carried out Alexander's orders and created an institution whose history and influence reached far and wide, withstood the test of time and left an enormous legacy to the European intellectual tradition. The library was founded in the early 3rd century BC by Ptolemy Soter I, one of Alexander the Great's best generals. Soter found Demetrios of Phaleron, a student of Aristotle, to fulfil Alexander's wish and establish a library. Demetrios helped Theophrastos to establish a school modelled on Aristotle's Lykeion and Plato's Akademia, and the Library of Alexandria began to take shape with a collection of 200,000 rolls.

The special structure of the library, designed in the Peripatetic style, was introduced by the Macedonian rulers with the intention of establishing a Hellenism with different principles. Demetrios, as advisor to the king, started the collections with works on statecraft, kingship and monarchy. In the space allocated to the Library he had two facilities, the Museum and the Library itself.

In co-operation with the Museum and the Library, the Museum and the Library continue to study medicine, mathematics, astronomy, mathematical geography, anatomy and physiology. These studies develop through analyses. In addition to experiments and observations, the sources produced before or at that time provide a great deal of guidance. With a special garden where plants and animals collected from various states are brought together, an observatory, an exhibition hall, a gallery collecting works of art, the library has become a very suitable environment for scientific and artistic studies. Although the aims of the Museum and the Library overlapped, their mandates were different. A biblion for scholars and a mouseion dedicated to the Muses. The museum was headed by a priest of Moses, called epistates or director. Under the supervision of this priest and with the encouragement of Ptolemy Philadelphos II, in 283 BC a community of scholars and scholars was formed, consisting of 30 to 50 members, including no women, who received a salary for their private teaching and were exempt from taxes. The scholars living here were obliged to give lectures and conferences. The number of students attending these lectures increased over time to 14,000. They studied philosophy, medicine, natural sciences, mathematics and took lessons from jurists who analysed and discussed the law.

The linguists who formed the grammar rules of ancient languages, geographers who drew the first maps of the world, poets, philosophers who influenced the world of thought with their different schools, who grew up in Alexandria, which became a centre of science in time, obtained their equipment through the library. The Library, run by a specialised librarian appointed by the king, consisted of many wings and porches with shelves (theke) lined up along covered passages. The first librarian, Demetrios, was succeeded by Zenodotus of Ephesus (283-245 BC). Among Zenodotus' assistants was Kallimakhos of Kyrenia, who, although never officially a librarian, initiated the world's first subject catalogue for the library, the Pinakles (tablets). By the time of Kallimakhos, the library had over 400,000 mixed scrolls and an additional 90,000 single scrolls.

At first, scholars wrote on parchment scrolls preserved in linen or leather fireplaces and stored them on shelves in the hall or archway. Later, in Roman times, they wrote on manuscripts in the form of codexes, which were kept in wooden chests (armaria). The most numerous of the library staff were the scribes (charakitai) and translators, called charta because they wrote on papyrus. As the collection expanded, a branch was formed. This was the Serapeion, located in the Temple of Serapis and built by Ptolemy III to house a new Greco-Egyptian cult, in the south-west of the city, some distance from the royal precinct. It soon held more than 40,000 items, and eventually many smaller libraries sprang up throughout the city.

Greek translations and copies of many manuscripts from Greek, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern and Persian civilisations were prepared here. Great importance was attached to the development of the Alexandria Library's collection, and large sums were paid to obtain a manuscript from a distant place when necessary. Thanks to its geographical location and its library, Alexandria became the centre of famous scientists of the period. The houses of science in the complex we call the library hosted many scientists from different branches and played an important role in the development of science. If we give examples of some of these scientists;

- Eucleides (330-275 BC) was one of the most famous scientists who worked and taught in Alexandria. His book of geometry, with its axioms, postulates, theorems and proofs, has been described as the most influential book in Western thought after the Bible.

- Apollonius (262-190 BC) Apollonius of Perges worked on conic sections - ellipses, parabolas and hyperbolas - discovered by Menaekhmos in 350 BC. These studies were used unchanged 2000 years later by Kepler and Newton to determine the properties of planetary orbits.

- Aristarchus (310-230 BC) In Alexandria, 1100 years before Copernicus proved that the universe was heliocentred and the earth was its satellite, Aristarchus expressed the same idea.

- Archimedes (287-212 BC) Archimedes, one of the most important scientists of Alexandria, conducted research on physics and geometry, statics and hydrostatics, mechanics, levers, and put them into practice. He showed the number pi in its present values.

- Eratosthenes (276-194 BC) Eratosthenes, the first to invent and use the system of latitude and longitude in addition to the word geography, is known as the chief mathematician and librarian of the Alexandrian Museum and the founder of physical geography. He gained his fame with the calculation of the circumference of the earth. Eratosthenes found the distance of the sun from the earth to be 92 million miles; the correct distance is 93 million miles.

- Ptolemy (Cladius Ptolemeus AD 85-165) Ptolemy, who was interested in astronomy and optics, was most famous for his work on geography, in which he synthesised the astronomical scholars of his time. The Arabic translation of Almagest (Encyclopaedia of Astronomy) was transmitted to the West. Almagest is interpreted as a great work expressing mathematical synthesis in astronomy.

- Galenos (AD 129-216) Galenos was one of the greatest physicians after Hippocrates, the Ionian physician and the father of medicine. Galenos' general theory on the functions of the body remained valid until Harvey discovered the circulation of blood.

In addition to these, the Alexandria Museum and Library, where scientists such as Herophilus, Hipparchus, Aedesia, Pappus, Theon and Hypatia were trained, had become a place where everything that could be known about Babylonian, Egyptian, Jewish and Greek thought was collected, codified, systematised and controlled by the beginning of the Christian era. Alexandria became the foundation of the text-centred culture of the Western tradition. The discipline required by collection and classification and the importance attached to scholarship were essential to academic professionalism. However, it began to lose its influence with the spread of Christianity.

Bibliography;

- MacLeod, Roy "The Library of Alexandria, the Learning Centre of the Ancient World" (2005).

- Ortaylı, İlber " Alexandria Library " Türk Kütüphaneciliği, 20,1 (2006).

- Keseroğlu ve Demir “ Antikçağda Bilim ve Kütüphane” Türk Kütüphaneciliği 30, 3 (2016).

- Özpek, Burak Bilgehan “ İskenderiye Kütüphanesi’nin Yükselişi ve Düşüşü” Kültür, Eylül-Ekim Cilt: 6 Sayı: 64