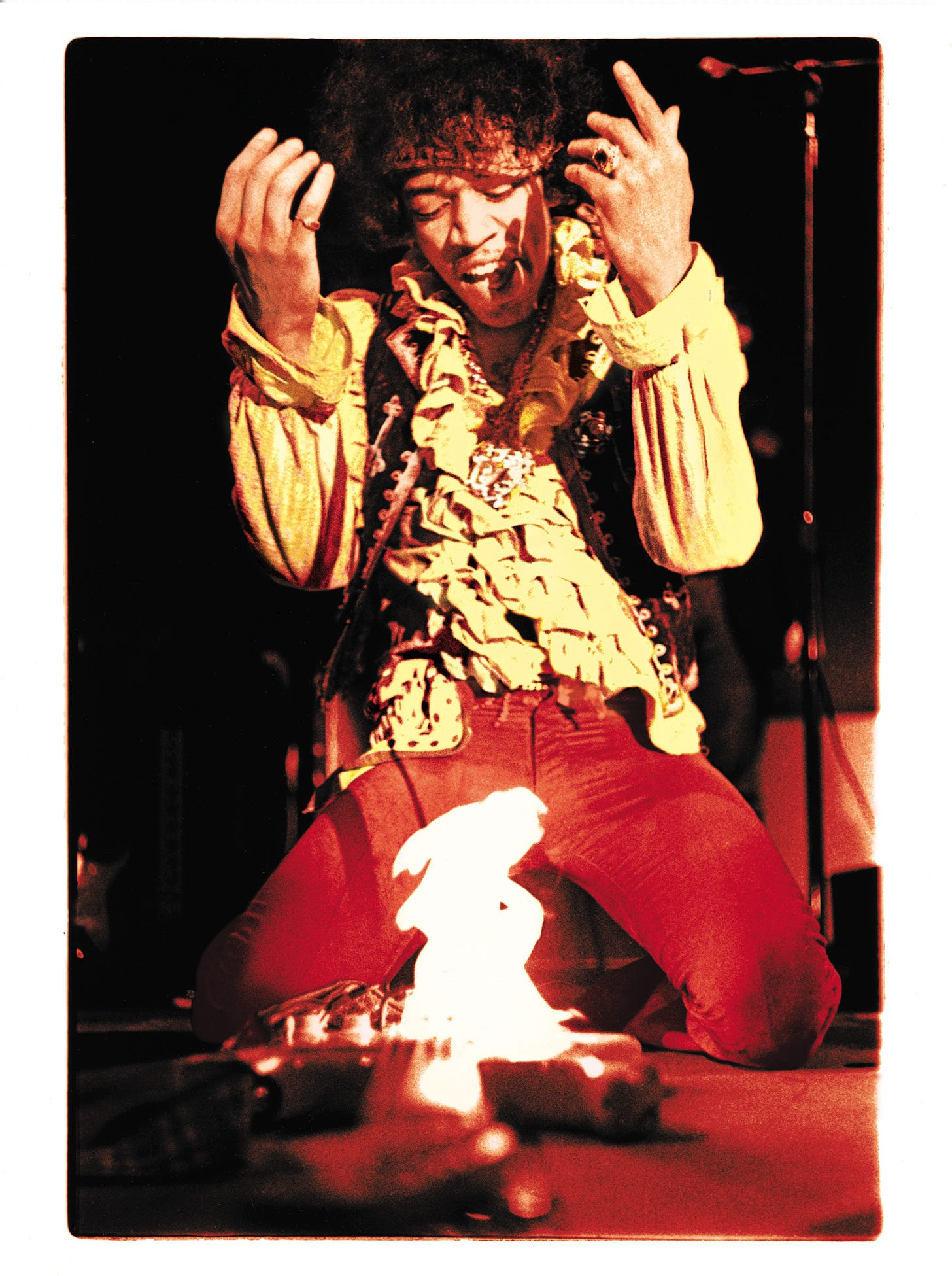

The Most Famous Shot in Rock & Roll

The Most Famous Shot in Rock & Roll

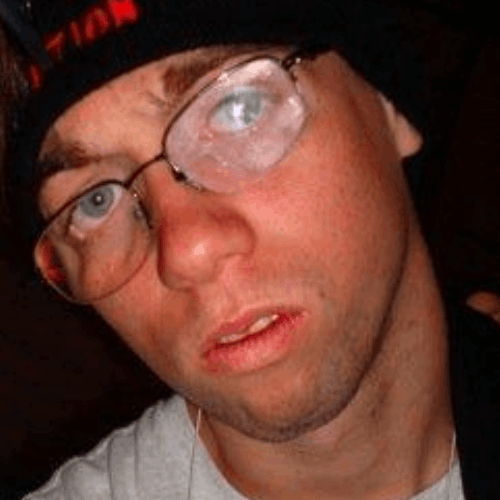

In 1967, high school junior Ed Caraeff heard about a "rock and roll festival" up the coast in Monterey. With the help of a borrowed camera, he took the photograph of a lifetime.

Photograph by Ed Caraeff

You may not know Ed Caraeff’s name, but if you’re a fan of ‘60s and ‘70s rock, you’ve admired at least a few of the countless album covers and live shots he’s photographed in a long and storied career. Incredibly, when he took his most famous one in June of 1967, he was just 17 years old. Still a high school junior at Westchester High School in Los Angeles, he’d heard about a “rock and roll festival” up the coast in Monterey and headed there with some friends and a camera borrowed from his family’s optometrist. As he put it later:

I wasn’t a music lover that was there to enjoy the music and take a few snapshots. I was there to photograph it—and I did.

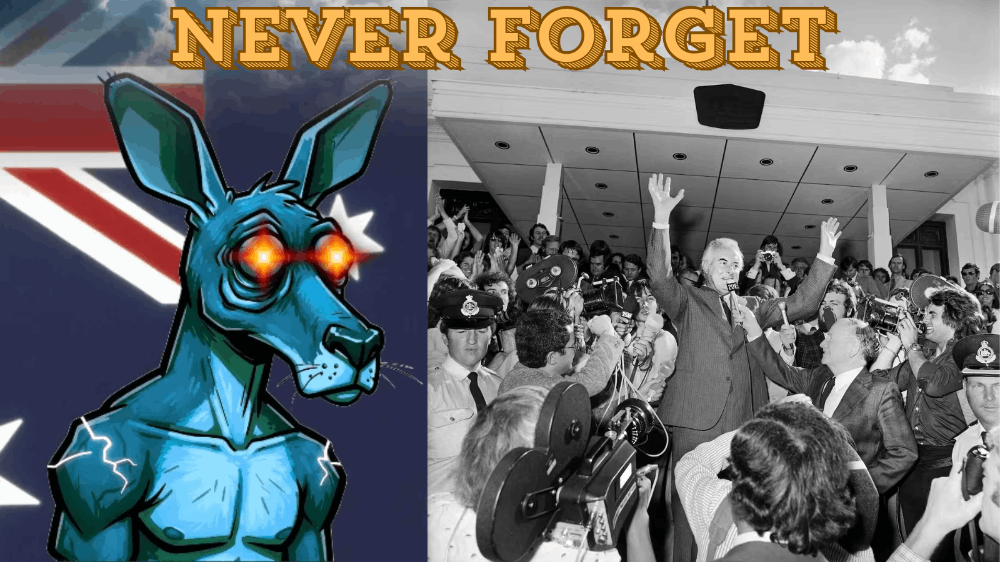

Caraeff’s shot seen ’round the world was of Jimi Hendrix at the close of his first American appearance. It’s a startling and otherworldly image: Hendrix kneels before a Fender Stratocaster laid on the stage, his mouth open, eyes closed in a timeless posture of both dominance and ecstasy.

Oh, and the guitar is on fire.

That photograph became the only image to make the cover of Rolling Stone twice. The song Hendrix was performing…erm, burning? “Wild Thing.” But we’ll get to that.

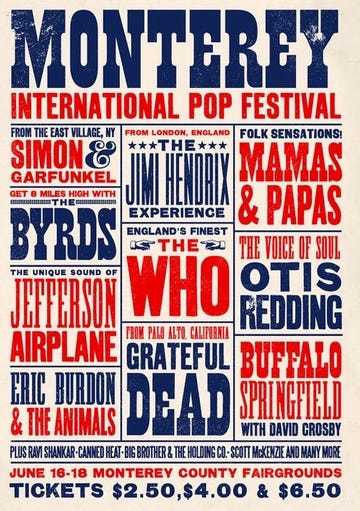

Now considered the first true rock festival, the Monterey International Pop Festival was a watershed.

Though miniscule by the standards of the gargantuan, decade-defining festivals to come—Woodstock was still two years in the future—Monterey was a signature event in the creation of “underground rock.”

In placing offbeat and regional up-and-comers such as Big Brother and the Holding Company and Laura Nyro alongside more established acts such as the Byrds and Simon & Garfunkel—and, crucially, interspersing rock and folk acts with soul and world music artists such as Otis Redding and Hugh Masekela—Monterey helped create a template for the wide-ranging programming of festivals (and auto-shuffled-playlists) to come.

Ed Caraeff wasn’t aware of this when he arrived at the festival. He was one of the lucky 8,000 or so to have actually scored a ticket (an estimated 25,000 to 90,000 others hung out in the nearby fairgrounds and parking lots). But as he related to us, he was given a crucial tip from someone he met in the photographers’ pool right in front of the stage:

I had been told by a German photographer just over from Europe to “save some film for this Jimi Hendrix cat.”

Little did he know how valuable that advice would turn out to be.

Monterey came together quickly. Working overtime over the course of a dizzying seven weeks, the organizers—John Phillips of the Mamas & the Papas, record producer Lou Adler, manager and entrepreneur Alan Pariser, and former Beatles’ publicist Derek Taylor—managed to assemble the framework of a workable festival.

The programming was top-notch, but equally notable were the artists who declined to perform, for various reasons. Previous drug arrests scotched the appearances of the Rolling Stones and Donovan. Bob Dylan was still recuperating from his devastating motorcycle accident. Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band backed out at the insistence of then-guitarist Ry Cooder, who was unnerved at bandleader Don Van Vliet’s somewhat graceless, LSD-inspired exit from the stage during a recent performance.

Most impactfully, the Beatles had turned down an invitation to perform. This was hardly a surprise, given that the band had announced they would cease touring the previous year. But for the pair of English artists Paul McCartney nominated in their stead, Monterey would be watershed moments in their careers.

The first one—The Who—weren’t complete unknowns in the United States. “Happy Jack” had made it to #24 on the Billboard Hot 100 the year before, and earlier songs such as “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere” and “My Generation” had enjoyed regional success in isolated pockets of the country.

Ironically, the other “English” artist—Jimi Hendrix—wasn’t English at all, though his backing band the Experience were longstanding London scenesters. But though he’d spent years backing up a host of superlative artists in the States—The Isley Brothers, Little Richard, King Curtis and others—Hendrix really was unknown in the United States.

That was all about to change.

The Who and The Experience had already shared a stage in London earlier that year and were fans of each others’ music, if wary ones. Hendrix had taken to destroying guitars at the end of his sets, an act The Who’s Pete Townshend felt, with some justification, was “his.”

By 1967, audiences fairly demanded to see some destruction at a Who concert, a fact Jimi Hendrix, newly arrived in London, took keen note of. Waiting backstage at an early Experience show in March of that year, Hendrix and manager Chas Chandler discussed ways in which they could grab some headlines. Journalist Keith Altham was in the room, and suggested that the Experience needed to do something more dramatic than the stage show of the Who. “Maybe I can smash up an elephant,” Hendrix joked, to which Altham replied, “Well, it’s a pity you can’t set fire to your guitar.”

That, too was about to change.

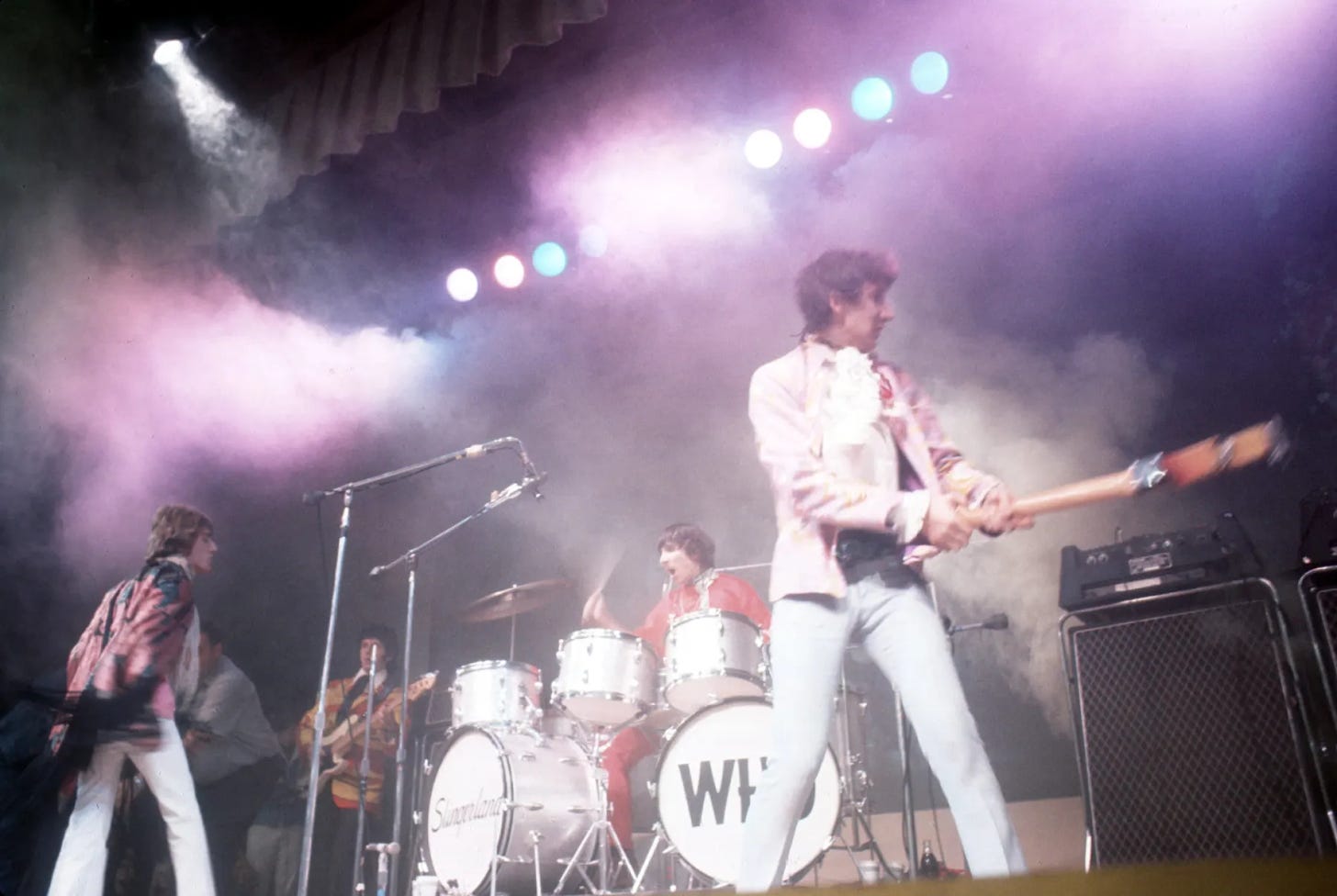

The Who at Monterey, Photograph Paul Ryan

On the night of June 18, 1967, Jimi Hendrix and Pete Townshend found themselves huddled, somewhat uncomfortably, in the backstage area at Monterey. As this was the first major US appearance for either band, neither wanted to follow the other. More pointedly, neither wanted to be second to demonstrate their instrument-smashing antics for a festival crowd.

After negotiations ended in a stalemate, the matter was decided with a coin toss, with The Who winning the first slot. But little remarked-upon though it may have been at the time, Townshend’s faceoff with Hendrix would prove to be a pivotal moment leading to The Who’s later (and greatest) work. As he later related in an interview with music journalist Matt Resnicoff:

Seeing Jimi absolutely, completely destroyed me. It was horrifying, because he took back Black music. He came and stole R&B back. He made it very evident that’s what he was doing…. I felt that I hadn’t the emotional equipment, really, the physical equipment, the natural psychic genius of somebody like Jimi. I realized that what I had was a bunch of gimmicks which he had come and taken away from me.

Regardless, The Who blasted through a 25-minute set, leaving the stage a virtual crime scene of trashed musical instruments. The Grateful Dead played next, a musical palate cleanser imbuing American roots music with a peculiarly hallucinogenic glow. It’s safe to say that nearly no one in the audience had an inkling of what was coming next.

The stage was reset for the next act of the night, loaded—somewhat ominously—both with new Marshall 100-Watt stacks and borrowed Dual Showman amps, then Fender’s largest and most powerful offering.

Whoever this “Jimi Hendrix” was, it was clear he was not messing around.

Sightings of the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones were a white-hot rumor snaking through the crowd. Now the doomed prince of the London scene made his presence known, taking the mic and, in a somewhat wan voice nearly drowned by excited cheers, introduced his “very good friend…the most exciting guitarist I’ve ever heard.”

By this point in the night, Ed Caraeff had managed to score perhaps the best spot in the entire auditorium: Standing on a folding chair in the photographers’ pool, wedged right against center stage. As the Jimi Hendrix Experience took the stage, the audience’s surprise was nearly palpable. As Caraeff related to us:

Ninety-five percent of the crowd that night had no idea who The Jimi Hendrix Experience was or what they looked like: A fashionable power trio, two skinny white London dudes with a black guy playin’ a guitar like no one else. Lotsa ATTITUDE!

Now, half a century after the fact, it’s difficult to reinhabit the context of Hendrix’s groundbreaking set that night. Rock and roll was still young in 1967, and much of what had seeped to the public’s consciousness was made by white artists self-consciously adopting Black artists’ styles.

Whatever the audience’s scant expectations, Jimi Hendrix was determined to defy them. Here was a Black man dressed in the most flamboyant, even confrontational hippie garb imaginable, playing electric guitar with jaw-dropping fluency and expression, and delivering it at crushing, never-before-experienced volume.

Thrilling though his performances are to hear, listening without seeing is cold comfort. Jimi Hendrix was above all a performer, and one of those rare individuals one simply cannot not watch. Fortunately, we have that luxury, as the festival was captured by documentarian D.A. Pennebaker for the 1968 documentary Monterey Pop, with more Hendrix footage released in 1985’s Jimi Plays Monterey.

If sex was the implicit force driving rock and roll, on stage Hendrix made this outrageously and abundantly explicit. Alternately his lover, his helpless captive, and the embodiment of his manhood, in his hands the electric guitar became a weapon of mass destruction.

If Hendrix felt any nervousness regarding his debut American performance, by the end of the set it had clearly evaporated. Singularly at ease and playful at the mic before that final number, he laments to the spellbound audience that he can’t: “…Just grab you, man and just, oooohhhh….”

The Experience ripped through nine songs that night, five of them covers. Some we’ve examined before, including his definitive rendition of “Hey, Joe,” a song which had been kicking around the States for several years at that point. But if we were forced to pick a single song to represent that epochal performance, it would have to be his set-ending rendition of “Wild Thing.”

We’ve examined the song previously. Composed by American Chip Taylor but made famous by The Troggs, a group of semi-competent guitar-bashers from suburban England who took it to the Top Ten for two giddy months in 1966, the song was a near-perfect encapsulation of the lust and primitivism imbuing early rock and roll.

As described in the book Becoming Jimi Hendrix, the song elicited an instant and powerful reaction from the young guitarist. Erstwhile girlfriend Carol Shiroky recalls that the first time he heard it played on the radio, Hendrix jumped out of the shower—naked and dripping, hair in curlers— and, grabbing his guitar, gave her an impromptu performance.

In a night full of surprises, Hendrix’s “Wild Thing” was surely the topper. If The Troggs’ version is primal, pregnant with promise (or naked lust), Hendrix’s take is an overdose of sexual fulfillment. He knows it, too: Grinding the back of his guitar, humping his amplifier, shooting unabashed come-ons and lighthearted taunts at the audience. It’s an astonishing performance from start to finish.

Calling this last number “The English and American anthem combined,” he kicks it off with a growl of feedback, a sound which in mid-1967 still sounded more like an interstellar transmission than anything made by humans. A moment’s pause, then that unmistakable, three-chord caveman grind.

Hendrix is at his utter best here. Cocksure, fiery and playful, he pulls out all the stops: Playing slides with his elbow, turning a somersault during his solo. He knows he’s won over the audience lock, stock, and barrel. Even his vocal performance—the instrument he was at times paralyzingly insecure about—is assured, as loose and free as his guitar playing. Listen to his ad-libs, tongue clicks, and throwaways here: “Aw shucks, I love you.”

Speaking of that solo, it’s Hendrix’s own addition. After all, what Jimi Hendrix song would be complete without a guitar solo? But just as Hendrix teases the audience on mic, so too does he with his guitar. That twisting, raga-esque figure he delivers is a quote from “Strangers in the Night,” Frank Sinatra’s smash hit Billboard #1 single (and album) from the previous year, a song which, in its own, urbane way, delivered much the same message as “Wild Thing.” And Hendrix played it with one hand–his non-playing right hand at that.

Hendrix played the next chorus with his guitar slung, impossibly, behind his back. And as the song crashed towards its climax, Ed Caraeff was in the perfect position to capture a moment of exquisite destructive and erotic power.

Hendrix had already laid his Stratocaster on the stage and was mounting it in an uncomfortable but mesmerizing display of dominance. Then, with drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Noel Redding unleashing a sonic hellstorm and his amplifiers unleashing squalling sheets of feedback, Hendrix abruptly rose, reached for something hidden behind an amp, and began to anoint his tortured instrument.

Now fully in possession of his power, his merest gesture brimming with unallayed sexual potency—sparing just a final kiss for the naptha-soaked Stratocaster—he strikes a match and drops it upon the guitar. In an instant, the instrument is in flames.

Caraeff, already blasted by his close proximity to three high-powered guitar amps, was now in a different sort of pickle, close enough that he had to shield his face from the heat of the burning guitar. But he knew this was a moment that would not be repeated. Working the camera’s lever to advance the roll, he found it was stuck. That meant there was only one shot left, and it would have to count. As Jimi Hendrix raised his fingers, seemingly conjuring fire with his bare hands, Caraeff took his final photograph of the night.

It was recently pointed out to me that what makes the burning guitar picture unique is that Jimi came down on his knees to my level, standing up on a chair jammed against the stage, four feet from a burning guitar. After that shot, even though there was no film left in my borrowed camera, I didn’t move the camera as that hot burning guitar was getting smashed to flying bits. It was common sense to protect my exposed face!

It’s one of the most iconic and arresting images in the entire pantheon of rock and roll. Hendrix’s tragic end was as yet unwritten then, but as the Los Angeles Times went on to report, in the course of that single performance, Jimi Hendrix “graduated from rumour to legend.”

The remainder of Jimi Hendrix’s life would not lack for eventfulness.

Massive commercial breakthrough; a phantasmagoric and drugged-out tour of the United States in 1968; an ascent to become the highest-paid rock artist in the world; the decade-defining performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at Woodstock the following year. In short, the very embodiment of rock and roll in the decade it came of age.

So too for young Ed Caraeff. Not long after the close of the Monterey International Pop Festival, Jimi Hendrix visited Caraeff’s home turf – Hollywood. Caraeff found out that the guitarist was staying in a two-story motel on Sunset Boulevard, developed a couple of black and white prints—including the burning guitar photo—in his high school darkroom, skipped school during his lunch hour, and drove off to show Hendrix his work. Incredibly, they became friends. The next night, Caraeff picked him up and they drove together to a party.

Just pause for a moment, if you would, and imagine that you show up to a high-school party with your new buddy. And that buddy happens to be Jimi Hendrix.

After that, Caraeff was allowed complete access to every show for years. He’d go on to shoot untold thousands of rock photographs, of anyone (and seemingly everyone) ranging from Captain Beefheart to Elton John to the Stooges.

Now that, dear readers, is rock and roll.