Uneasy Doublets in Etymology

Ever wonder why the words "language" and "tongue" sound so similar? Most likely not, as those terms have a whole different tone. The fact that both originate from the same word—which was used in a language known as Proto-Indo-European (PIE) about 6000 years ago—might surprise you. it word was probably meant to mean "tongue," and it sounded something like "dn̥ҵʰwéh₂s" (don't even ask me how to pronounce it). The PIE language divided into numerous languages as it moved around Europe, and the way sounds changed among them varied as well. Dn̵̥ʰwéh₂s became '*tungǭ' in the Proto-Germanic language of northern Europe, and finally English became the "tongue". The word first appeared as "dingua" in Latin, then as "lingua" and lastly as "language" in old French before being eventually borrowed into English. That makes these two words distant cousins. "Linguistics" is related as well.

We refer to these word-cousins as "doublets" when they speak the same language. Some of them, like "ward" and "guard," or "pyre" and "fire," have like appearances and sounds. Certain words, like "word" and "verb," sound completely different but have similar meanings. Examples are "cow" and "beef." Others—like "head" and "chef"—seem to be very distinct from one another. However, as they all share the same ancestral term, these pairs are connected. Despite being separated by millennia of history, they have come to speak the same language: English.

Many languages have doublets, but English has a lot more than most other languages because it is such a multilingual language. Doublets frequently involve three or more related terms. Due to the Germanic core of Old English vocabulary, a large number of French words have been borrowed into English, along with words from many other languages; as a result, words in Modern English often have quite distinct sounds depending on which root they came from.

In extreme circumstances, dozens of English words may have the same root word in PIE, with words entering the language from several sources.

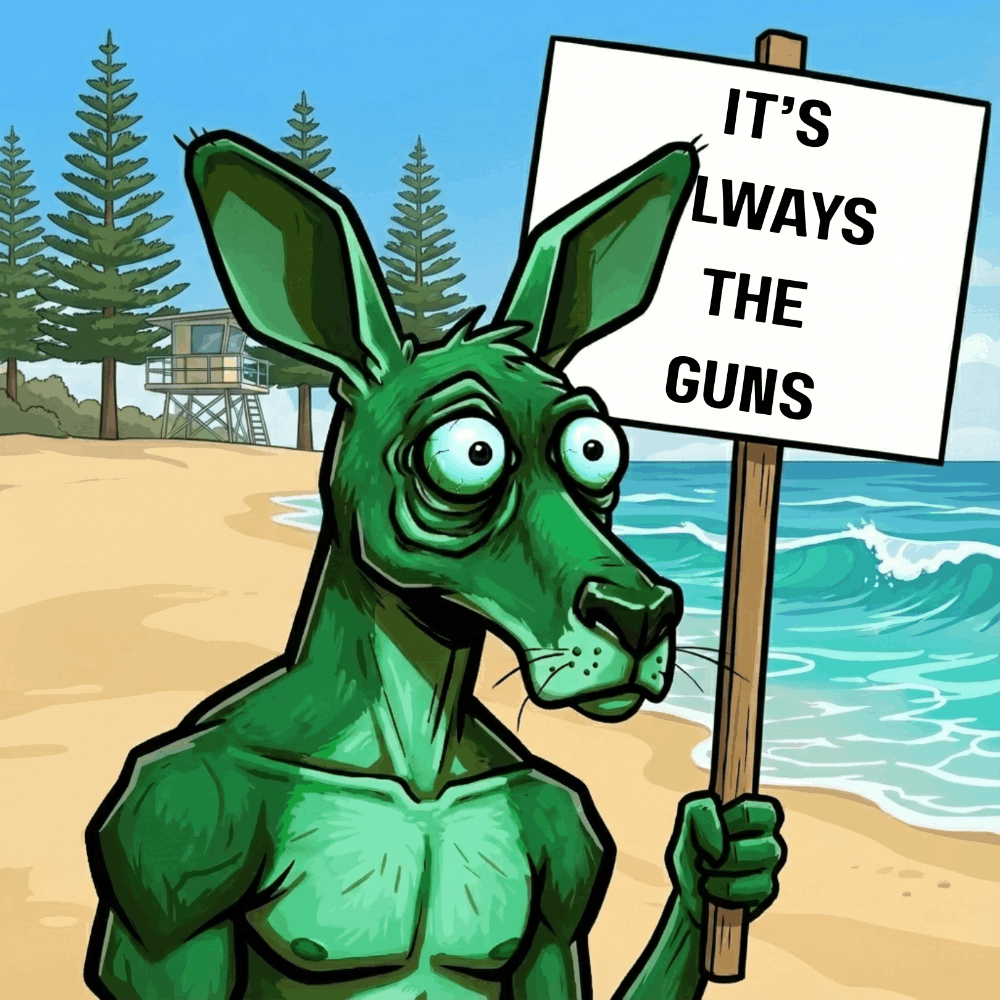

Let's examine two basic terms that have an abnormally high number of doublets: "king" and "royal."

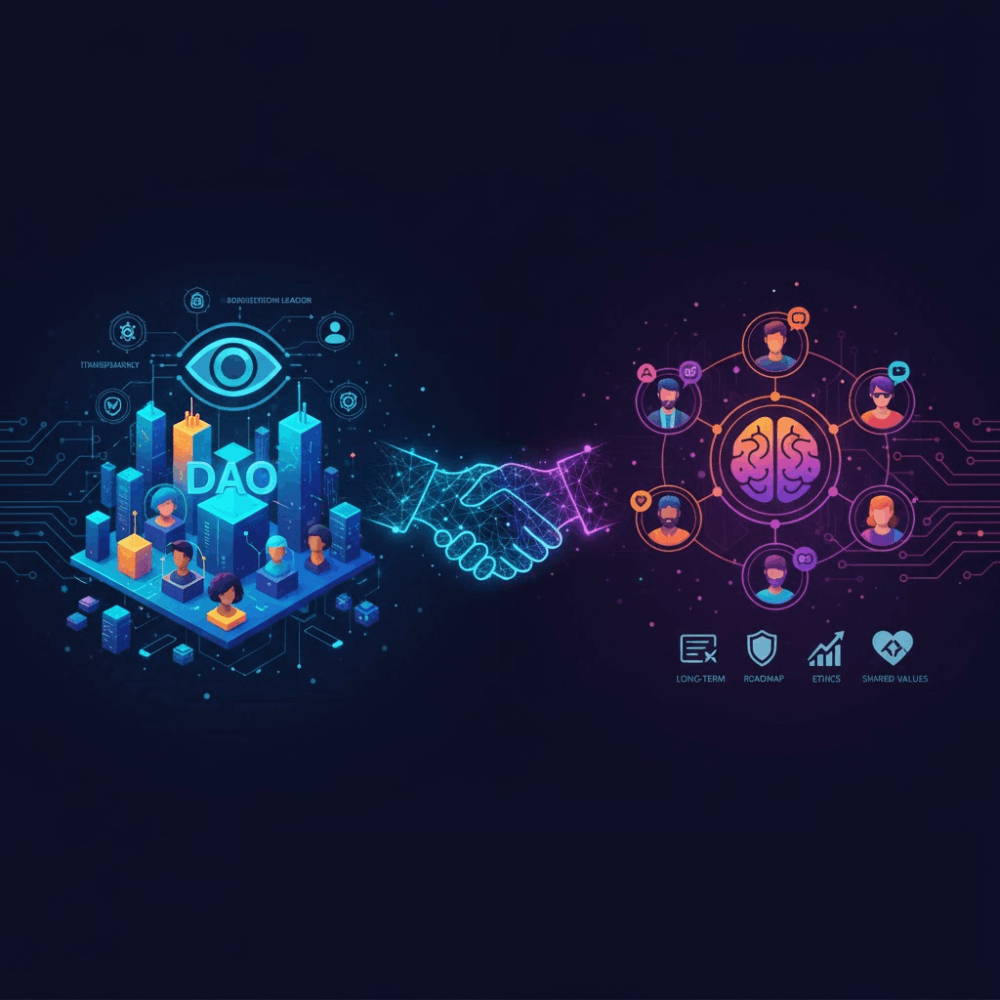

Despite having similar meanings, these two terms are not doublets because their etymologies are completely unrelated. But they all form a branch of extraordinarily intricate and twisted trees, with dozens of doublets in each tree. I thought it would be entertaining to display those two trees here as illustrations of the complexity of these doublets:

Since all 30 of these English terms are derived from the Proto-Indo-European word *h₃reĵ, which means "right," they are connected to the word "royal." The small * indicates that the word is rebuilt using all of its ancestors' words.

Recall that this only displays the tree's branches that terminate in English words. There are approximately 450 Indo European languages spoken worldwide, and many of them will include vocabulary that is connected to these. Not to mention all the non-Indo-European languages that have incorporated vocabulary from the IE, such as the various unrelated South Asian languages that have adopted Hindi's word for "king," raj/raja.

About a dozen terms, largely from Old French, that are associated with royalty and rule may be found in this tree. This makes logical when you consider that Old French and Anglo-Norman speakers dominated England for many years. The term "king" is absent from this tree because it derives from a separate word, the PIE word *ɵenh₁, which means "give birth."

The word "king" is connected to these 32 words. As you can see, the /g/ changed to a /k/ in Germanic languages like English, but it remained a /g/ in Latin and Greek—with the exception of a few words where it was eliminated entirely. Doublets are an excellent tool for observing the many ways in which sounds have evolved across related languages.

While creating this cartoon, I learned a lot. However, the biggest surprise may have been realizing halfway through that my first name, Ryan, should be on the Hreg tree! I will absolutely be doing more postings similar to this one because it's fascinating to see the subtle and intriguing connections between words and languages.