5 Things Everyone Knows Wrong About Cleopatra

-Despite being one of the most famous women in history, the real Cleopatra (69-30 BC) is shrouded in mystery.

Although she ruled Egypt for 22 years, commanded riches unmatched in the ancient world, and bore children to two of the most powerful men in Rome, the stories told over the centuries - Cleopatra the cunning, amoral seductress - are mostly propaganda written by her enemies.

Pr Pratt, a professor of history at Montclair State University and author of "Cleopatra: A Sourcebook", we talked to Prudence Jones about the truth about Cleopatra VII. Here are five facts that can bust some myths. Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

1. Cleopatra was not Egyptian One thing we know for sure:

Cleopatra was not Egyptian. Cleopatra was the last of the Macedonian Greek kings and queens who ruled Egypt beginning with the conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 BC. After Alexander's death, his general Ptolemy I was appointed king of Egypt, which he ruled as a Greek from the Hellenistic capital Alexandria. Born in 69 BC, Cleopatra was the daughter of Ptolemy XII. It is not known who Cleopatra's mother was, but it is thought to have been Cleopatra V Tryphaena, the wife of Ptolemy XII and also his sister or half-sister.

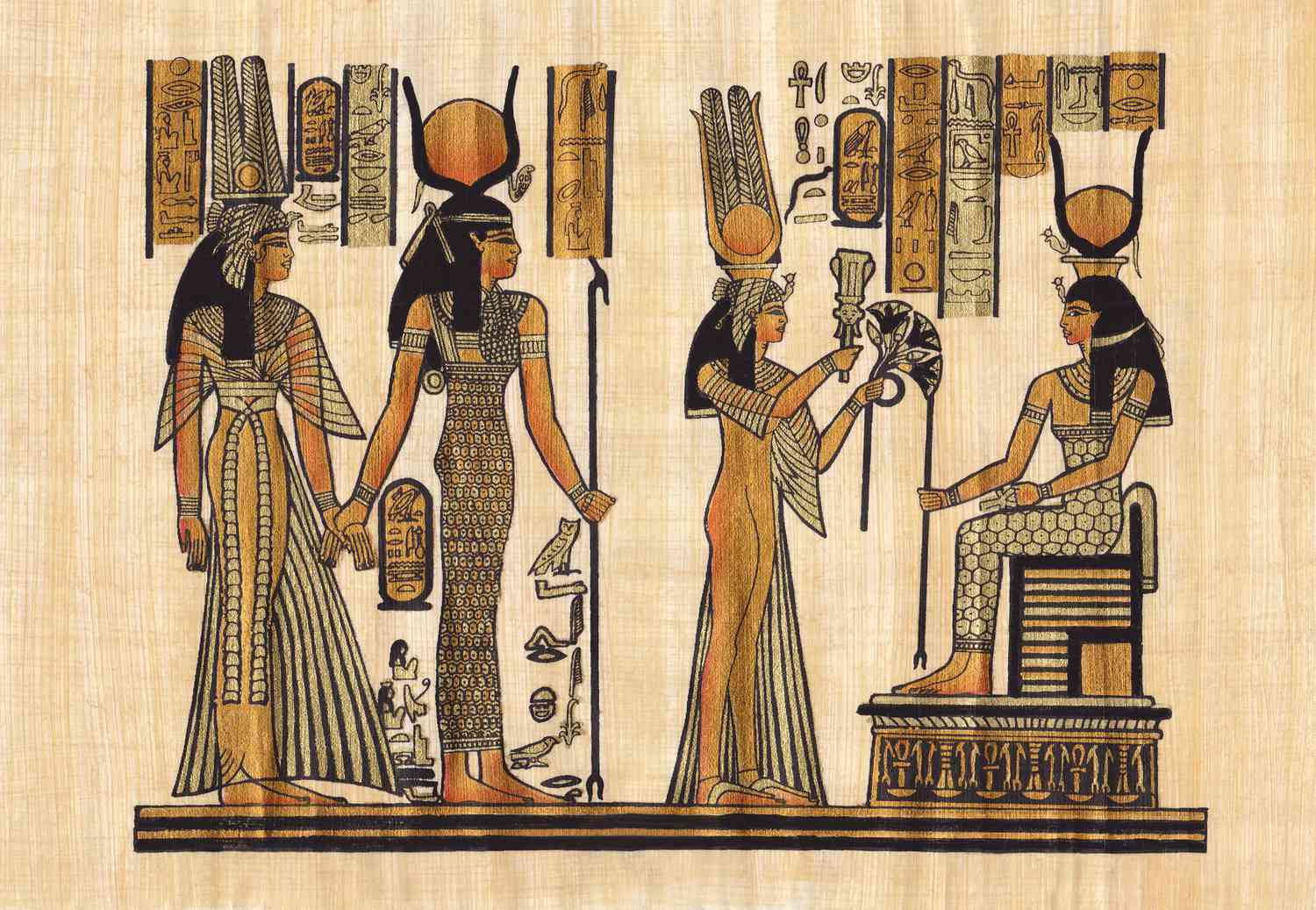

Although Cleopatra was not ethnically Egyptian, she made explicit references to Egyptian religion and culture, such as identifying herself with the goddess Isis. Cleopatra was also the first queen in the centuries-long Ptolemaic Dynasty to take the trouble to learn to speak Egyptian. "The others were not so keen," says Jones.

2. She Captivated Not With Her Beauty, But With Her Intelligence and Charm

Egypt's Roman enemies tried to slander Cleopatra, portraying her as a prostitute queen whose physical beauty alone captivated great men like Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. But even the Roman historian Plutarch, writing a century after Cleopatra's death, said that Cleopatra was much more than her looks, describing her as "so unique... as to impress all who saw her".

"But there was an irresistible charm in conversing with him, and there was something stimulating about his presence, combined with the persuasiveness of his speech and the character that somehow radiated in his behavior towards others," Plutarch wrote. "There was also sweetness in the tones of his voice; and his tongue, like an instrument with many strings, could easily turn to any language he wished, so that he rarely needed an interpreter in his conversations with the Barbarians."

In addition to speaking Greek and Egyptian, Cleopatra was fluent in at least six other languages. A highly educated woman, Cleopatra published two known texts, one on body care and another on weights and measures for medicine and commerce.

Compared to the military-minded Antony, who was "not known as the sharpest nail in the box," Jones says, "Cleopatra was renowned for her intelligence."

3. 'Love affair' with Caesar was a strategic alliance

Cleopatra was not, as the Roman poet Lucan described her, a "lecherous rage" ruled only by her confused passions. Jones says she had only two romantic partners in her short 39-year life, and both relationships were political as well as personal.

When Cleopatra ascended the Egyptian throne at the age of 18, she inherited a kingdom in decline. Rome was the rising power in the Mediterranean and Egypt's independence was under threat. Worse, her younger brother and co-ruler (and husband - it's complicated) were trying to dethrone her.

When Julius Caesar came to Egypt after his rival Pompey, Cleopatra saw the opportunity to gain a powerful Roman ally. According to Plutarch's famous account, the middle-aged Caesar first saw Cleopatra when she snuck into his quarters and rolled off a carpet (or, more likely, a laundry basket).

The young Cleopatra won Caesar's affection, reclaimed the throne and sealed the alliance with the birth of her son, whom she not-so-veiledly named Caesarion ("Little Caesar"). She now had family ties with Rome.

4 Relationship with Antony IV? Also Political

Cleopatra's later affair with Mark Antony (Caesar's second-in-command) was immortalized by Shakespeare in his play "Antony and Cleopatra" as one of the most legendary and tragic love affairs in history, but it too served primarily a political purpose.

Egypt may have had great wealth and resources, but after Caesar's murder Cleopatra knew that her kingdom was still subject to the whims of the reigning superpower Rome.

"Cleopatra recognized that Egypt needed a strong protector to remain independent," Jones says. Caesar's death had created a power vacuum in Rome, and two important men - Octavian, Caesar's chosen heir and nephew, and Antony, the ambitious politician and general - fought a civil war to fill it. Octavian had the financial backing of the Senate, but Antony desperately needed money to pay his soldiers. Cleopatra once again saw a "lair".

Plutarch, writing of the first meeting between Antony and Cleopatra, paints a picture of an older and wiser Cleopatra, intent on winning her prize:

"Caesar had met her when she was a young girl, ignorant of the world, but she was to meet Antony in the period of life when women's beauty is at its most splendid and their intellect at its fullest maturity. She made great preparations for her journey, buying money, gifts and precious ornaments that a very rich kingdom could afford, but she placed her greatest hopes in her own magic and charms."

Cleopatra had no need for magic. Jones says that Antony needed money and Cleopatra was the richest woman in the world. In exchange for her financial support, Antony became Egypt's ally and defender against Roman encroachment and gave Cleopatra three more heirs (whom she eventually married).

5. Suicide by snake? Come on!

The real-life double suicide of Antony and Cleopatra, recorded by Plutarch, provided a fitting tragic ending to Shakespeare's play. However, the event probably did not unfold exactly as Shakespeare wrote it.

After an unsuccessful naval battle against Octavian, Antony, mistakenly believing Cleopatra to be dead, falls on his own sword and eventually dies of his wounds in her arms. Cleopatra, not wanting to be exposed as a prisoner of war on the streets of Rome, has a poisonous snake brought into her room. In the last scene of the play, she wraps the snake around her chest.

In Plutarch's version, the snake (specifically an asp) was hidden in a basket of large figs. "It is said that the snake was brought along with the figs and leaves and hid under them, because Cleopatra had ordered it that way, so that the reptile could cling to her body without her realizing it. But when he took some of the figs and saw her, he said, 'There, you see,' and held out his arm for her to bite."

However, even Plutarch admits that there are various rumors about Cleopatra's death and that "no one knows the truth" because she was said to have carried the poison in a hollow comb and hid it in her hair.

Modern Cleopatra scholars say that poison was a much simpler and quicker way to die, but that Cleopatra probably included the more dramatic snake story in her suicide note to Caesar.

After Cleopatra's death, Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire. Octavian later became known as the Roman emperor Caesar Augustus.

Thanks for reading.