Our ‘bee-eye camera’ helps us support bees, grow food and protect the environment

Walking through our gardens in Australia, we may not realise that buzzing around us is one of our greatest natural resources. Bees are responsible for pollinating about a third of food for human consumption, and data on crop production suggests that bees contribute more than US$235 billion to the global economy each year.

By pollinating native and non-native plants, including many ornamental species, honeybees and Australian native bees also play an essential role in creating healthy communities – from urban parks to backyard gardens.

Despite their importance to human and environmental health, it is amazing how little we know how about our hard working insect friends actually see the world.

By learning how bees see and make decisions, it’s possible to improve our understanding of how best to work with bees to manage our essential resources.

Insects in the city: a honeybee forages in the heart of Sydney. Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees get stressed at work too (and it might be causing colony collapse)

How bee vision differs from human vision

A new documentary on ABC TV, The Great Australian Bee Challenge, is teaching everyday Australians all about bees. In it, we conducted an experiment to demonstrate how bees use their amazing eyes to find complex shapes in flowers, or even human faces.

Humans use the lens in our eye to focus light onto our retina, resulting in a sharp image. By contrast, insects like bees use a compound eye that is made up of many light-guiding tubes called ommatidia.

The top of each ommatidia is called a facet. In each of a bees’ two compound eyes, there are about 5000 different ommatidia, each funnelling part of the scene towards specialised sensors to enable visual perception by the bee brain.

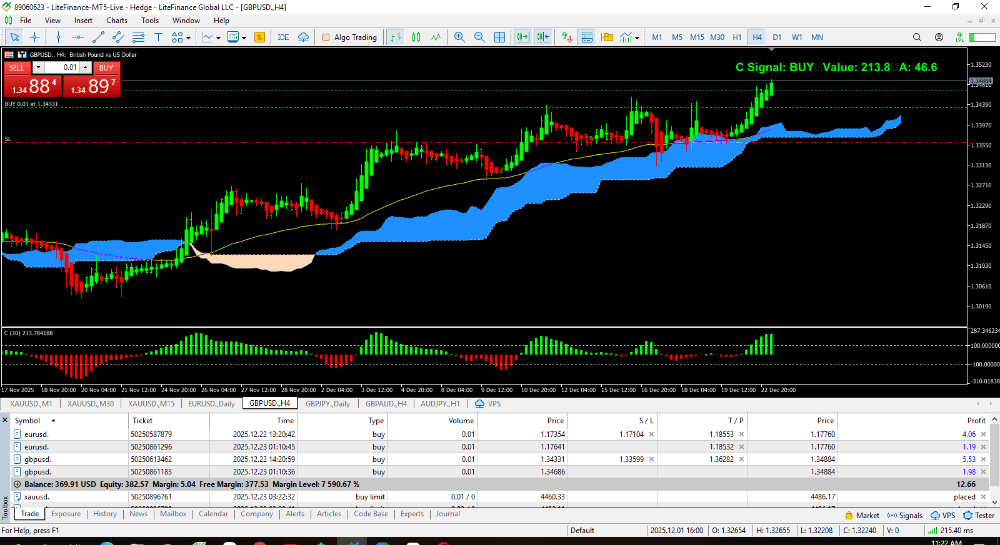

How we see fine detail with our eyes, and how a bee eye camera views the same information at a distance of about 15cm. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Since each ommatidia carries limited information about a scene due to the physics of light, the resulting composite image is relatively “grainy” compared to human vision. The problem of reduced visual sharpness poses a challenge for bees trying to find flowers at a distance.

To help draw bees’ attention, flowers that are pollinated by bees have typically evolved to send very strong colour signals. We may find them beautiful, but flowers haven’t evolved for our eyes. In fact, the strongest signals appeal to a bee’s ability to perceive mixtures of ultraviolet, blue and green light.

Yellow flower (Gelsemium sempervirens) as it appears to our eye, as taken through a UV sensitive camera, and how it likely appears to a bee. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees can learn the difference between European and Australian Indigenous art styles in a single afternoon

Building a bee eye camera

Despite all of our research, it can still be hard to imagine how a bee sees.

So to help people (including ourselves) visualise what the Walking through our gardens in Australia, we may not realise that buzzing around us is one of our greatest natural resources. Bees are responsible for pollinating about a third of food for human consumption, and data on crop production suggests that bees contribute more than US$235 billion to the global economy each year.

By pollinating native and non-native plants, including many ornamental species, honeybees and Australian native bees also play an essential role in creating healthy communities – from urban parks to backyard gardens.

Despite their importance to human and environmental health, it is amazing how little we know how about our hard working insect friends actually see the world.

By learning how bees see and make decisions, it’s possible to improve our understanding of how best to work with bees to manage our essential resources.

Insects in the city: a honeybee forages in the heart of Sydney. Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees get stressed at work too (and it might be causing colony collapse)

How bee vision differs from human vision

A new documentary on ABC TV, The Great Australian Bee Challenge, is teaching everyday Australians all about bees. In it, we conducted an experiment to demonstrate how bees use their amazing eyes to find complex shapes in flowers, or even human faces.

Humans use the lens in our eye to focus light onto our retina, resulting in a sharp image. By contrast, insects like bees use a compound eye that is made up of many light-guiding tubes called ommatidia.

The top of each ommatidia is called a facet. In each of a bees’ two compound eyes, there are about 5000 different ommatidia, each funnelling part of the scene towards specialised sensors to enable visual perception by the bee brain.

How we see fine detail with our eyes, and how a bee eye camera views the same information at a distance of about 15cm. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Since each ommatidia carries limited information about a scene due to the physics of light, the resulting composite image is relatively “grainy” compared to human vision. The problem of reduced visual sharpness poses a challenge for bees trying to find flowers at a distance.

To help draw bees’ attention, flowers that are pollinated by bees have typically evolved to send very strong colour signals. We may find them beautiful, but flowers haven’t evolved for our eyes. In fact, the strongest signals appeal to a bee’s ability to perceive mixtures of ultraviolet, blue and green light.

Yellow flower (Gelsemium sempervirens) as it appears to our eye, as taken through a UV sensitive camera, and how it likely appears to a bee. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees can learn the difference between European and Australian Indigenous art styles in a single afternoon

Building a bee eye camera

Despite all of our research, it can still be hard to imagine how a bee sees.

So to help people (includinWalking through our gardens in Australia, we may not realise that buzzing around us is one of our greatest natural resources. Bees are responsible for pollinating about a third of food for human consumption, and data on crop production suggests that bees contribute more than US$235 billion to the global economy each year.

By pollinating native and non-native plants, including many ornamental species, honeybees and Australian native bees also play an essential role in creating healthy communities – from urban parks to backyard gardens.

Despite their importance to human and environmental health, it is amazing how little we know how about our hard working insect friends actually see the world.

By learning how bees see and make decisions, it’s possible to improve our understanding of how best to work with bees to manage our essential resources.

Insects in the city: a honeybee forages in the heart of Sydney. Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees get stressed at work too (and it might be causing colony collapse)

How bee vision differs from human vision

A new documentary on ABC TV, The Great Australian Bee Challenge, is teaching everyday Australians all about bees. In it, we conducted an experiment to demonstrate how bees use their amazing eyes to find complex shapes in flowers, or even human faces.

Humans use the lens in our eye to focus light onto our retina, resulting in a sharp image. By contrast, insects like bees use a compound eye that is made up of many light-guiding tubes called ommatidia.

The top of each ommatidia is called a facet. In each of a bees’ two compound eyes, there are about 5000 different ommatidia, each funnelling part of the scene towards specialised sensors to enable visual perception by the bee brain.

How we see fine detail with our eyes, and how a bee eye camera views the same information at a distance of about 15cm. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Since each ommatidia carries limited information about a scene due to the physics of light, the resulting composite image is relatively “grainy” compared to human vision. The problem of reduced visual sharpness poses a challenge for bees trying to find flowers at a distance.

To help draw bees’ attention, flowers that are pollinated by bees have typically evolved to send very strong colour signals. We may find them beautiful, but flowers haven’t evolved for our eyes. In fact, the strongest signals appeal to a bee’s ability to perceive mixtures of ultraviolet, blue and green light.

Yellow flower (Gelsemium sempervirens) as it appears to our eye, as taken through a UV sensitive camera, and how it likely appears to a bee. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees can learn the difference between European and Australian Indigenous art styles in a single afternoon

Building a bee eye camera

Despite all of our research, it can still be hard to imagine how a bee sees.

So to help people (includinWalking through our gardens in Australia, we may not realise that buzzing around us is one of our greatest natural resources. Bees are responsible for pollinating about a third of food for human consumption, and data on crop production suggests that bees contribute more than US$235 billion to the global economy each year.

By pollinating native and non-native plants, including many ornamental species, honeybees and Australian native bees also play an essential role in creating healthy communities – from urban parks to backyard gardens.

Despite their importance to human and environmental health, it is amazing how little we know how about our hard working insect friends actually see the world.

By learning how bees see and make decisions, it’s possible to improve our understanding of how best to work with bees to manage our essential resources.

Insects in the city: a honeybee forages in the heart of Sydney. Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees get stressed at work too (and it might be causing colony collapse)

How bee vision differs from human vision

A new documentary on ABC TV, The Great Australian Bee Challenge, is teaching everyday Australians all about bees. In it, we conducted an experiment to demonstrate how bees use their amazing eyes to find complex shapes in flowers, or even human faces.

Humans use the lens in our eye to focus light onto our retina, resulting in a sharp image. By contrast, insects like bees use a compound eye that is made up of many light-guiding tubes called ommatidia.

The top of each ommatidia is called a facet. In each of a bees’ two compound eyes, there are about 5000 different ommatidia, each funnelling part of the scene towards specialised sensors to enable visual perception by the bee brain.

How we see fine detail with our eyes, and how a bee eye camera views the same information at a distance of about 15cm. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Since each ommatidia carries limited information about a scene due to the physics of light, the resulting composite image is relatively “grainy” compared to human vision. The problem of reduced visual sharpness poses a challenge for bees trying to find flowers at a distance.

To help draw bees’ attention, flowers that are pollinated by bees have typically evolved to send very strong colour signals. We may find them beautiful, but flowers haven’t evolved for our eyes. In fact, the strongest signals appeal to a bee’s ability to perceive mixtures of ultraviolet, blue and green light.

Yellow flower (Gelsemium sempervirens) as it appears to our eye, as taken through a UV sensitive camera, and how it likely appears to a bee. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees can learn the difference between European and Australian Indigenous art styles in a single afternoon

Building a bee eye camera

Despite all of our research, it can still be hard to imagine how a bee sees.

So to help people (includinWalking through our gardens in Australia, we may not realise that buzzing around us is one of our greatest natural resources. Bees are responsible for pollinating about a third of food for human consumption, and data on crop production suggests that bees contribute more than US$235 billion to the global economy each year.

By pollinating native and non-native plants, including many ornamental species, honeybees and Australian native bees also play an essential role in creating healthy communities – from urban parks to backyard gardens.

Despite their importance to human and environmental health, it is amazing how little we know how about our hard working insect friends actually see the world.

By learning how bees see and make decisions, it’s possible to improve our understanding of how best to work with bees to manage our essential resources.

Insects in the city: a honeybee forages in the heart of Sydney. Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees get stressed at work too (and it might be causing colony collapse)

How bee vision differs from human vision

A new documentary on ABC TV, The Great Australian Bee Challenge, is teaching everyday Australians all about bees. In it, we conducted an experiment to demonstrate how bees use their amazing eyes to find complex shapes in flowers, or even human faces.

Humans use the lens in our eye to focus light onto our retina, resulting in a sharp image. By contrast, insects like bees use a compound eye that is made up of many light-guiding tubes called ommatidia.

The top of each ommatidia is called a facet. In each of a bees’ two compound eyes, there are about 5000 different ommatidia, each funnelling part of the scene towards specialised sensors to enable visual perception by the bee brain.

How we see fine detail with our eyes, and how a bee eye camera views the same information at a distance of about 15cm. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Since each ommatidia carries limited information about a scene due to the physics of light, the resulting composite image is relatively “grainy” compared to human vision. The problem of reduced visual sharpness poses a challenge for bees trying to find flowers at a distance.

To help draw bees’ attention, flowers that are pollinated by bees have typically evolved to send very strong colour signals. We may find them beautiful, but flowers haven’t evolved for our eyes. In fact, the strongest signals appeal to a bee’s ability to perceive mixtures of ultraviolet, blue and green light.

Yellow flower (Gelsemium sempervirens) as it appears to our eye, as taken through a UV sensitive camera, and how it likely appears to a bee. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees can learn the difference between European and Australian Indigenous art styles in a single afternoon

Building a bee eye camera

Despite all of our research, it can still be hard to imagine how a bee sees.

So to help people (includinWalking through our gardens in Australia, we may not realise that buzzing around us is one of our greatest natural resources. Bees are responsible for pollinating about a third of food for human consumption, and data on crop production suggests that bees contribute more than US$235 billion to the global economy each year.

By pollinating native and non-native plants, including many ornamental species, honeybees and Australian native bees also play an essential role in creating healthy communities – from urban parks to backyard gardens.

Despite their importance to human and environmental health, it is amazing how little we know how about our hard working insect friends actually see the world.

By learning how bees see and make decisions, it’s possible to improve our understanding of how best to work with bees to manage our essential resources.

Insects in the city: a honeybee forages in the heart of Sydney. Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees get stressed at work too (and it might be causing colony collapse)

How bee vision differs from human vision

A new documentary on ABC TV, The Great Australian Bee Challenge, is teaching everyday Australians all about bees. In it, we conducted an experiment to demonstrate how bees use their amazing eyes to find complex shapes in flowers, or even human faces.

Humans use the lens in our eye to focus light onto our retina, resulting in a sharp image. By contrast, insects like bees use a compound eye that is made up of many light-guiding tubes called ommatidia.

The top of each ommatidia is called a facet. In each of a bees’ two compound eyes, there are about 5000 different ommatidia, each funnelling part of the scene towards specialised sensors to enable visual perception by the bee brain.

How we see fine detail with our eyes, and how a bee eye camera views the same information at a distance of about 15cm. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Since each ommatidia carries limited information about a scene due to the physics of light, the resulting composite image is relatively “grainy” compared to human vision. The problem of reduced visual sharpness poses a challenge for bees trying to find flowers at a distance.

To help draw bees’ attention, flowers that are pollinated by bees have typically evolved to send very strong colour signals. We may find them beautiful, but flowers haven’t evolved for our eyes. In fact, the strongest signals appeal to a bee’s ability to perceive mixtures of ultraviolet, blue and green light.

Yellow flower (Gelsemium sempervirens) as it appears to our eye, as taken through a UV sensitive camera, and how it likely appears to a bee. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees can learn the difference between European and Australian Indigenous art styles in a single afternoon

Building a bee eye camera

Despite all of our research, it can still be hard to imagine how a bee sees.

So to help people (includinWalking through our gardens in Australia, we may not realise that buzzing around us is one of our greatest natural resources. Bees are responsible for pollinating about a third of food for human consumption, and data on crop production suggests that bees contribute more than US$235 billion to the global economy each year.

By pollinating native and non-native plants, including many ornamental species, honeybees and Australian native bees also play an essential role in creating healthy communities – from urban parks to backyard gardens.

Despite their importance to human and environmental health, it is amazing how little we know how about our hard working insect friends actually see the world.

By learning how bees see and make decisions, it’s possible to improve our understanding of how best to work with bees to manage our essential resources.

Insects in the city: a honeybee forages in the heart of Sydney. Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees get stressed at work too (and it might be causing colony collapse)

How bee vision differs from human vision

A new documentary on ABC TV, The Great Australian Bee Challenge, is teaching everyday Australians all about bees. In it, we conducted an experiment to demonstrate how bees use their amazing eyes to find complex shapes in flowers, or even human faces.

Humans use the lens in our eye to focus light onto our retina, resulting in a sharp image. By contrast, insects like bees use a compound eye that is made up of many light-guiding tubes called ommatidia.

The top of each ommatidia is called a facet. In each of a bees’ two compound eyes, there are about 5000 different ommatidia, each funnelling part of the scene towards specialised sensors to enable visual perception by the bee brain.

How we see fine detail with our eyes, and how a bee eye camera views the same information at a distance of about 15cm. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Since each ommatidia carries limited information about a scene due to the physics of light, the resulting composite image is relatively “grainy” compared to human vision. The problem of reduced visual sharpness poses a challenge for bees trying to find flowers at a distance.

To help draw bees’ attention, flowers that are pollinated by bees have typically evolved to send very strong colour signals. We may find them beautiful, but flowers haven’t evolved for our eyes. In fact, the strongest signals appeal to a bee’s ability to perceive mixtures of ultraviolet, blue and green light.

Yellow flower (Gelsemium sempervirens) as it appears to our eye, as taken through a UV sensitive camera, and how it likely appears to a bee. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees can learn the difference between European and Australian Indigenous art styles in a single afternoon

Building a bee eye camera

Despite all of our research, it can still be hard to imagine how a bee sees.

So to help people (includinWalking through our gardens in Australia, we may not realise that buzzing around us is one of our greatest natural resources. Bees are responsible for pollinating about a third of food for human consumption, and data on crop production suggests that bees contribute more than US$235 billion to the global economy each year.

By pollinating native and non-native plants, including many ornamental species, honeybees and Australian native bees also play an essential role in creating healthy communities – from urban parks to backyard gardens.

Despite their importance to human and environmental health, it is amazing how little we know how about our hard working insect friends actually see the world.

By learning how bees see and make decisions, it’s possible to improve our understanding of how best to work with bees to manage our essential resources.

Insects in the city: a honeybee forages in the heart of Sydney. Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees get stressed at work too (and it might be causing colony collapse)

How bee vision differs from human vision

A new documentary on ABC TV, The Great Australian Bee Challenge, is teaching everyday Australians all about bees. In it, we conducted an experiment to demonstrate how bees use their amazing eyes to find complex shapes in flowers, or even human faces.

Humans use the lens in our eye to focus light onto our retina, resulting in a sharp image. By contrast, insects like bees use a compound eye that is made up of many light-guiding tubes called ommatidia.

The top of each ommatidia is called a facet. In each of a bees’ two compound eyes, there are about 5000 different ommatidia, each funnelling part of the scene towards specialised sensors to enable visual perception by the bee brain.

How we see fine detail with our eyes, and how a bee eye camera views the same information at a distance of about 15cm. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Since each ommatidia carries limited information about a scene due to the physics of light, the resulting composite image is relatively “grainy” compared to human vision. The problem of reduced visual sharpness poses a challenge for bees trying to find flowers at a distance.

To help draw bees’ attention, flowers that are pollinated by bees have typically evolved to send very strong colour signals. We may find them beautiful, but flowers haven’t evolved for our eyes. In fact, the strongest signals appeal to a bee’s ability to perceive mixtures of ultraviolet, blue and green light.

Yellow flower (Gelsemium sempervirens) as it appears to our eye, as taken through a UV sensitive camera, and how it likely appears to a bee. Sue Williams and Adrian Dyer/RMIT University

Read more: Bees can learn the difference between European and Australian Indigenous art styles in a single afternoon

Building a bee eye camera

Despite all of our research, it can still be hard to imagine how a bee sees.

So to help people (including ourselves) visualise what the g ourselves) visualise what the g ourselves) visualise what the g ourselves) visualise what the g ourselves) visualise what the g ourselves) visualise what the g ourselves) visualise what the