Exploring the Intricate History and Symbolism of Labyrinths

Intro

In Greek mythology, the Labyrinth, known as Labúrinthos in Ancient Greek, was a complex and perplexing structure crafted by the legendary artisan Daedalus for King Minos of Crete at Knossos. Its primary purpose was to confine the Minotaur, a monstrous creature eventually slain by the hero Theseus. Daedalus, in his ingenious construction, made the Labyrinth so intricate that he could barely navigate it himself after completing it. While early Cretan coins occasionally featured branching (multicursal) patterns, the Classical design that emerged around 430 BC was a single-path (unicursal) layout without branching or dead ends. This specific design became associated with the Labyrinth on coins, even though both logic and literary descriptions emphasized the Minotaur being trapped in a complex branching maze. The representations of the mythological Labyrinth in visual arts from Roman times to the Renaissance predominantly depicted unicursal designs. The reintroduction of branching mazes occurred during the Renaissance when hedge mazes gained popularity.

While early Cretan coins occasionally featured branching (multicursal) patterns, the Classical design that emerged around 430 BC was a single-path (unicursal) layout without branching or dead ends. This specific design became associated with the Labyrinth on coins, even though both logic and literary descriptions emphasized the Minotaur being trapped in a complex branching maze. The representations of the mythological Labyrinth in visual arts from Roman times to the Renaissance predominantly depicted unicursal designs. The reintroduction of branching mazes occurred during the Renaissance when hedge mazes gained popularity.

In the English language, the term "labyrinth" is commonly used interchangeably with "maze." However, due to the historical prevalence of unicursal representations of the mythological Labyrinth, some scholars and enthusiasts distinguish between the two. In this specialized context, a "maze" refers to a complex, branching, multicursal puzzle with multiple paths and directions, while a "labyrinth" is a unicursal design with a single path to the center, offering a straightforward route without navigational challenges. Unicursal labyrinth patterns appeared on various mediums such as pottery, basketry, body art, and etchings on cave or church walls. The Romans employed decorative unicursal designs on walls and floors using tiles or mosaics. Some labyrinths, set in floors or on the ground, are large enough to be walked. Throughout history, unicursal patterns have been utilized in group rituals, private meditation, and, more recently, for therapeutic purposes in hospitals and hospices.

Unicursal labyrinth patterns appeared on various mediums such as pottery, basketry, body art, and etchings on cave or church walls. The Romans employed decorative unicursal designs on walls and floors using tiles or mosaics. Some labyrinths, set in floors or on the ground, are large enough to be walked. Throughout history, unicursal patterns have been utilized in group rituals, private meditation, and, more recently, for therapeutic purposes in hospitals and hospices.

Ancient labyrinths

Cretan Labyrinth

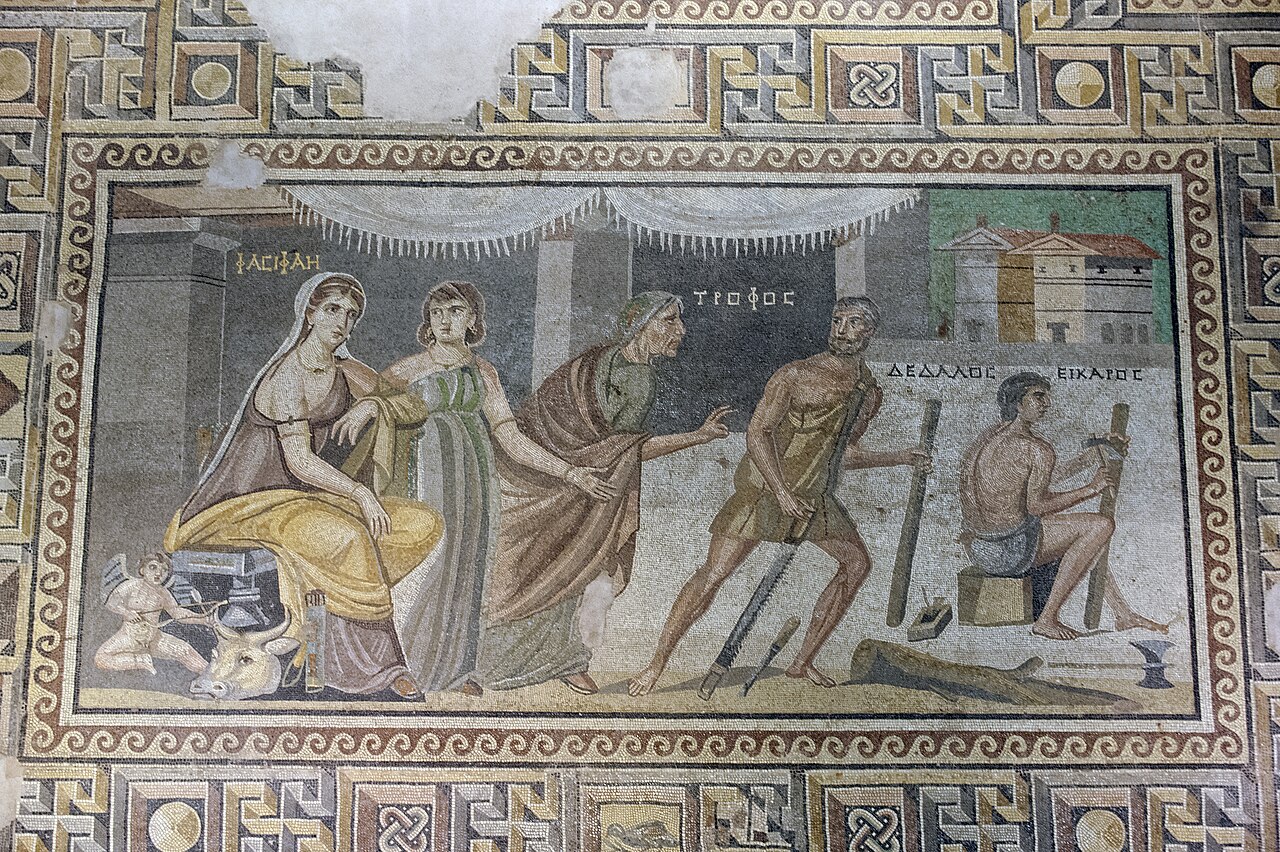

A mosaic from Zeugma, Commagene, now housed in the Zeugma Mosaic Museum, portrays Daedalus, his son Icarus, Queen Pasiphaë, and two of her attendants.

Excavations by archaeologist Arthur Evans at the Bronze Age site of Knossos led to the suggestion that the palace could be the Labyrinth of Daedalus. Evans discovered various bull motifs, including a depiction of a man leaping over a bull's horns, and labrys carvings on the walls. Drawing from a passage in the Iliad, it's proposed that the palace served as a dancing ground for Ariadne, crafted by Daedalus, where young men and women would dance together. In popular legend, the palace became associated with the Minotaur myth.

In the 2000s, archaeologists explored alternative sites for the labyrinth. Oxford University geographer Nicholas Howarth expressed skepticism about Evans's hypothesis and investigated the Skotino cave, concluding it was naturally formed. Another contender is a series of tunnels at Gortyn, exhibiting smooth walls and columns, potentially man-made. This site aligns with a labyrinth symbol on a 16th-century map of Crete. A documentary produced for the National Geographic Channel showcased Howarth's investigation.

The Egyptian Labyrinth

Herodotus, in Book II of his Histories, referred to a labyrinthine building complex in Egypt near the City of Crocodiles, surpassing the pyramids. The structure, possibly a collection of funerary temples, was discovered at Hawara in the Faiyum Oasis during the nineteenth century by Flinders Petrie.

Pliny's Labyrinths

Pliny the Elder's Natural History mentions the Lemnian labyrinth, attributed to the legendary Smilis, and the Italian labyrinth in the tomb of Etruscan general Lars Porsena. The Lemnian labyrinth is considered a misunderstanding of the Samian temple's location, and Pliny's description of Porsena's tomb is unclear.

Ancient Labyrinths outside Europe

A design resembling the classical 7-course pattern appears in Native American culture among the Tohono O'odham people, featuring I'itoi, the "Man in the Maze." This pattern differs by being radial in design, with the entrance at the top. Unsubstantiated claims suggest early labyrinth figures in India, with securely datable examples appearing around 250 BC. Labyrinths are mentioned in Indian manuscripts and Tantric texts from the 17th century onward, often referred to as "Chakravyuha." Stone labyrinths have been preserved near the White Sea on the Solovetsky Islands, with the most notable being on Bolshoi Zayatsky Island. Archaeologists speculate about their age, suggesting they may be 2,000–3,000 years old.