Mahalia Jackson

Mahalia Jackson

Mahalia Jackson was an American gospel singer, widely considered one of the most influential vocalists of the 20th century. With a career spanning 40 years, Jackson was integral to the development and spread of gospel blues in black churches throughout the U.S. During a time when racial segregation was pervasive in American society, she met considerable and unexpected success in a recording career, selling an estimated 22 million records and performing in front of integrated and secular audiences in concert halls around the world.

The granddaughter of enslaved people, Jackson was born and raised in poverty in New Orleans. She found a home in her church, leading to a lifelong dedication and singular purpose to deliver God's word through song. She moved to Chicago as an adolescent and joined the Johnson Singers, one of the earliest gospel groups. Jackson was heavily influenced by musician-composer Thomas Dorsey, and by blues singer Bessie Smith, adapting Smith's style to traditional Protestant hymns and contemporary songs. After making an impression in Chicago churches, she was hired to sing at funerals, political rallies, and revivals. For 15 years, she functioned as what she termed a "fish and bread singer," working odd jobs between performances to make a living.

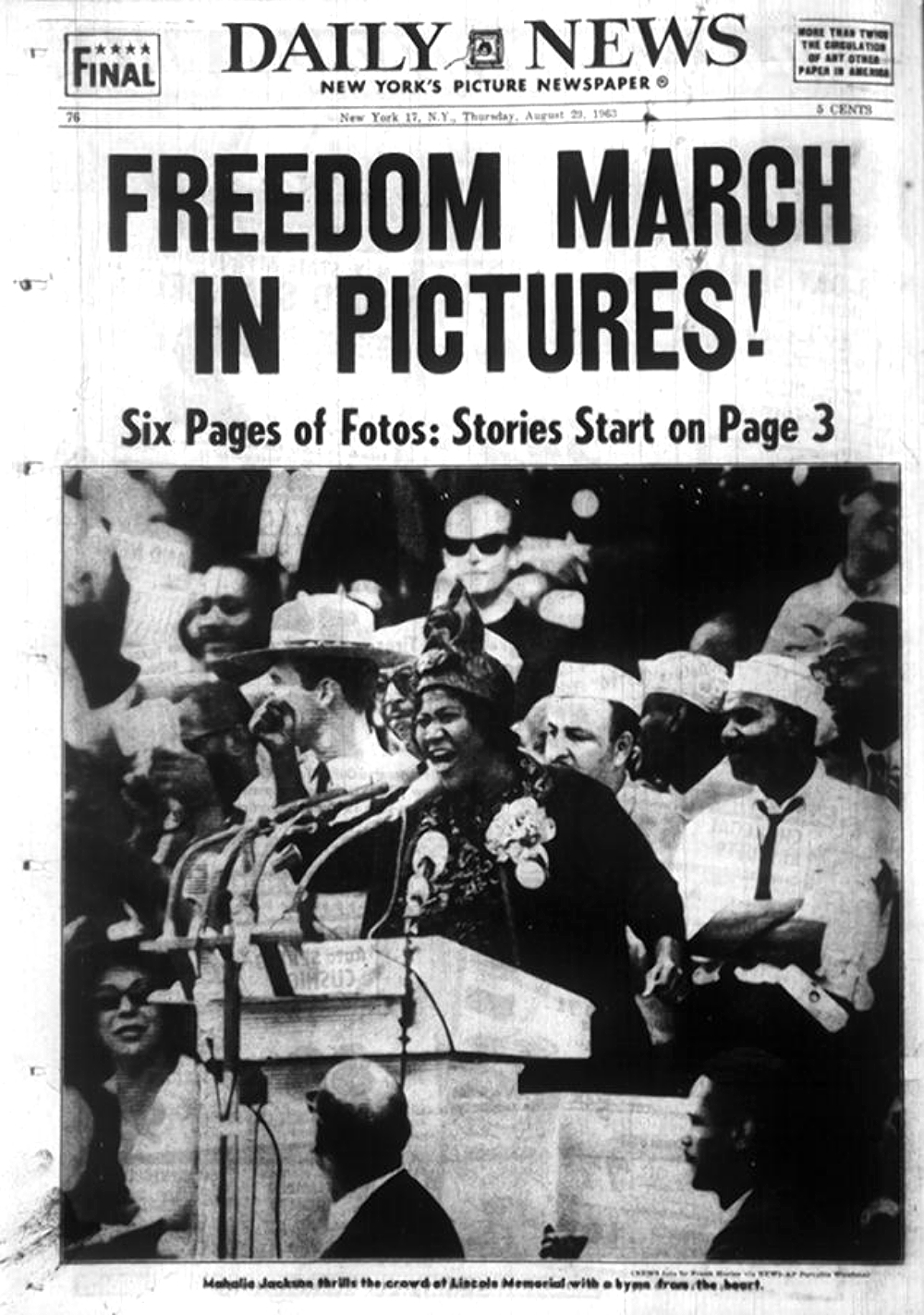

Nationwide recognition came for Jackson in 1947 with the release of "Move On Up a Little Higher," selling two million copies and hitting the number two spot on Billboard charts, both firsts for gospel music. Jackson's recordings captured the attention of jazz fans in the U.S. and France, and she became the first gospel recording artist to tour Europe. She regularly appeared on television and radio, and performed for many presidents and heads of state, including singing the national anthem at John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Ball in 1961. Motivated by her experiences living and touring in the South and integrating a Chicago neighborhood, she participated in the civil rights movement, singing for fundraisers and at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. She was a vocal and loyal supporter of Martin Luther King Jr. and a personal friend of his family.

Throughout her career, Jackson faced intense pressure to record secular music but turned down high-paying opportunities to concentrate on gospel. Completely self-taught, Jackson had a keen instinct for music, her delivery marked by extensive improvisation with melody and rhythm. She was renowned for her powerful contralto voice, range, enormous stage presence, and her ability to relate to her audiences, conveying and evoking intense emotion during performances. Passionate and at times frenetic, she wept and demonstrated physical expressions of joy while singing. Her success brought about international interest in gospel music, initiating the "Golden Age of Gospel," making it possible for many soloists and vocal groups to tour and record. Popular music as a whole felt her influence, and she is credited with inspiring rhythm and blues, soul, and rock and roll singing styles.

Mahalia Jackson was born to Charity Clark and Johnny Jackson, a stevedore and weekend barber. Clark and Jackson were unmarried, a common arrangement among black women in New Orleans at the time. He lived elsewhere, never joining Charity as a parent. Both sets of Mahalia's grandparents were born into slavery, her paternal grandparents on a rice plantation and her maternal grandparents on a cotton plantation in Pointe Coupee Parish about 100 miles (160 km) north of New Orleans.

Charity's older sister, Mahala "Duke" Paul, was her daughter's namesake, sharing the spelling without the "I". Duke hosted Charity and their five other sisters and children in her leaky three-room shotgun house on Water Street in New Orleans' Sixteenth Ward. The family called Charity's daughter "Halie"; she counted as the 13th person living in Aunt Duke's house. As Charity's sisters found employment as maids and cooks, they left Duke's, though Charity remained with her daughter, Mahalia's half-brother Peter, and Duke's son Fred.

Mahalia was born with bowed legs and infections in both eyes. Her eyes healed quickly but her Aunt Bell treated her legs with grease water massages with little result. For her first few years, Mahalia was nicknamed "Fishhooks" for the curvature of her legs.

The Clarks were devout Baptists, attending nearby Plymouth Rock Baptist Church. Sabbath was strictly followed; the entire house shut down on Friday evenings and did not open again until Monday morning. As members of the church, they were expected to attend services, participate in activities there, and follow a code of conduct: no jazz, no card games, and no "high life" - drinking or visiting bars or juke joints. Dancing was only allowed in the church when one was moved by the spirit.

Next door to Duke's house was a small Pentecostal church that Jackson never attended but stood outside during services and listened raptly. Music here was louder and more exuberant. The congregation included "jubilees" or uptempo spirituals in their singing. Shouting and stomping were regular occurrences, unlike at her own church. Jackson later remembered, "These people had no choir or no organ. They used the drum, the cymbal, the tambourine, and the steel triangle. Everybody in there sang, and they clapped and stomped their feet, and sang with their whole bodies. They had a beat, a rhythm we held on to from slavery days, and their music was so strong and expressive. It used to bring tears to my eyes."

When Jackson was five, her mother became ill and died, the cause unknown. Aunt Duke took in Jackson and her half-brother at another house on Esther Street. Duke was severe and strict, with a notorious temper. Jackson split her time between working, usually scrubbing floors and making moss-filled mattresses and cane chairs, playing along the levees catching fish and crabs and singing with other children, and spending time at Mount Moriah Baptist Church where her grandfather sometimes preached.

The full-time minister there gave sermons with a sad "singing tone" that Jackson later said would penetrate to her heart, crediting it with strongly influencing her singing style. Church became a home to Jackson where she found music and safety; she often fled there to escape her aunt's moods. She attended McDonough School 24, but was required to fill in for her various aunts if they were ill, so she rarely attended a full week of school; when she was 10, the family needed her more at home. She dropped out and began taking in laundry.

Jackson worked, and she went to church on Wednesday evenings, Friday nights, and most of the day on Sundays. Already possessing a big voice at age 12, she joined the junior choir. She was surrounded by music in New Orleans, more often blues pouring out of her neighbors' houses, although she was fascinated with second line funeral processions returning from cemeteries when the musicians played brisk jazz.

Her older cousin Fred, not as intimidated by Duke, collected records of both kinds. The family had a phonograph, and while Aunt Duke was at work, Jackson played records by Bessie Smith, Mamie Smith, and Ma Rainey, singing along while she scrubbed floors. Bessie Smith was Jackson's favorite and the one she most often mimicked.

Jackson's legs began to straighten on their own when she was 14, but conflicts with Aunt Duke never abated. Whippings turned into being thrown out of the house for slights and manufactured infractions and spending many nights with one of her nearby aunts. The final confrontation caused her to move into her own rented house for a month, but she was lonely and unsure of how to support herself. After two aunts, Hannah and Alice, moved to Chicago, Jackson's family, concerned for her, urged Hannah to take her back there with her after a Thanksgiving visit.

In a very cold December, Jackson arrived in Chicago. For a week, she was miserably homesick, unable to move off the couch until Sunday when her aunts took her to Greater Salem Baptist Church, an environment she felt at home in immediately, later stating it was "the most wonderful thing that ever happened to me." When the pastor called the congregation to witness, or declare one's experience with God, Jackson was struck by the spirit and launched into a lively rendition of "Hand Me Down My Silver Trumpet, Gabriel," to an impressed but somewhat bemused audience.

The power of Jackson's voice was readily apparent, but the congregation was unused to such an animated delivery. She was nonetheless invited to join the 50-member choir and a vocal group formed by the pastor's sons, Prince, Wilbur, and Robert Johnson, and Louise Lemon. They performed as a quartet, the Johnson Singers, with Prince as the pianist: Chicago's first black gospel group. Initially, they hosted familiar programs, singing at socials and Friday night musicals. They wrote and performed moral plays at Greater Salem with offerings going toward the church.

Jackson's arrival in Chicago occurred during the Great Migration, a massive movement of black Southerners to Northern cities. Between 1910 and 1970, hundreds of thousands of rural Southern blacks moved to Chicago, transforming a neighborhood in the South Side into Bronzeville, a black city within a city which was mostly self-sufficient, prosperous, and teeming in the 1920s.

This movement caused white flight, with whites moving to suburbs, leaving established white churches and synagogues with dwindling members. Their mortgages were taken over by black congregations in a good position to settle in Bronzeville. Members of these churches were, in Jackson's term, "society Negroes" who were well-educated and eager to prove their successful assimilation into white American society. Musical services tended to be formal, presenting solemnly delivered hymns written by Isaac Watts and other European composers. Shouting and clapping were generally not allowed as they were viewed as undignified. Special programs and musicals tended to feature sophisticated choral arrangements to prove the quality of the choir.

The difference between the styles in Northern urban churches and the South was vividly illustrated when the Johnson Singers appeared at a church one evening, and Jackson stood out to sing solo, scandalizing the pastor with her exuberant shouts. He accused her of blasphemy, bringing "twisting jazz" into the church. Jackson was momentarily shocked before retorting, "This is the way we sing down South!"

The minister was not alone in his apprehension. She was often so involved in singing she was mostly unaware of how she moved her body. To hide her movements, pastors urged her to wear loose-fitting robes which she often lifted a few inches from the ground, and they accused her of employing "snake hips" while dancing when the spirit moved her. Enduring another indignity, Jackson scraped together four dollars (equivalent to $68 in 2022) to pay a talented black operatic tenor for a professional assessment of her voice. She was dismayed when the professor chastised her: "You've got to learn to stop hollering. It will take time to build up your voice. The way you sing is not a credit to the Negro race. You've got to learn to sing songs so that white people can understand them."

Soon Jackson found the mentor she was seeking. Thomas A. Dorsey, a seasoned blues musician trying to transition to gospel music, trained Jackson for two months, persuading her to sing slower songs to maximize their emotional effect. Dorsey had a motive: he needed a singer to help sell his sheet music. He recruited Jackson to stand on Chicago street corners with him and sing his songs, hoping to sell them for ten cents a page. It was not the financial success Dorsey hoped for, but their collaboration resulted in the unintentional conception of gospel blues solo singing in Chicago.

References

- Jackson and Wylie, pp. 11–28.

- a b c Goreau, pp. 3–15.

- a b c d Burford 2019, pp. 33–64.

- a b Broughton, p. 53.

- ^ Broughton, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Burford 2020, p. 27.

- a b c Jackson and Wylie, pp. 29–38.

- a b Goreau, pp. 15–25.

- ^ Goreau, pp. 39–51.

- ^ Jackson and Wylie, p. 49.

- ^ Jackson and Wylie, pp. 39–50.

- a b c Goreau, pp. 51–61.

- ^ Darden, p. 211.

- ^ Harris pp. 91–116.