Victor Hugo

Victor Hugo

For other uses, see Victor Hugo (disambiguation).

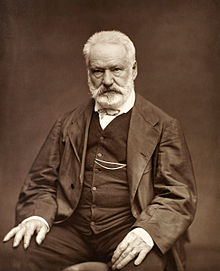

Victor Hugo Portrait by Étienne Carjat, 1876

Portrait by Étienne Carjat, 1876

BornVictor-Marie Hugo

26 February 1802

Besançon, Franche-Comté, FranceDied22 May 1885 (aged 83)

- Paris, FranceResting placePanthéon, ParisOccupationsPoetnovelistdramatistessayistpoliticianPolitical partyParty of Order (1848–1851)

- Independent liberal (1871)

- Republican Union (1876–1885)

SpouseAdèle Foucher

- (m. 1822; died 1868)Children5ParentsJoseph Léopold Hugo

- Sophie Trébuchet

Writing careerGenreNovelpoetrytheatreLiterary movementRomanticismYears active1829–1883Notable worksLes MisérablesRuy BlasThe Hunchback of Notre-DameSignature show

show

Offices held

Victor-Marie Hugo (French: [viktɔʁ maʁi yɡo] ⓘ; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885), sometimes nicknamed the Ocean Man, was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms.

His most famous works are the novels The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) and Les Misérables (1862). In France, Hugo is renowned for his poetry collections, such as Les Contemplations (The Contemplations) and La Légende des siècles (The Legend of the Ages). Hugo was at the forefront of the Romantic literary movement with his play Cromwell and drama Hernani. Many of his works have inspired music, both during his lifetime and after his death, including the opera Rigoletto and the musicals Les Misérables and Notre-Dame de Paris. He produced more than 4,000 drawings in his lifetime, and campaigned for social causes such as the abolition of capital punishment and slavery.

Although he was a committed royalist when young, Hugo's views changed as the decades passed, and he became a passionate supporter of republicanism, serving in politics as both deputy and senator. His work touched upon most of the political and social issues and the artistic trends of his time. His opposition to absolutism, and his literary stature, established him as a national hero. Hugo died on 22 May 1885, aged 83. He was given a state funeral in the Panthéon of Paris, which was attended by over 2 million people, the largest in French history.[1]

Early life[edit]

Victor-Marie was born on 26 February 1802 in Besançon in Eastern France. He was the youngest son of Joseph Léopold Sigisbert Hugo (1774–1828), a general in the Napoleonic army, and Sophie Trébuchet (1772–1821). The couple had two other sons: Abel Joseph (1798–1855) and Eugène (1800–1837). The Hugo family came from Nancy in Lorraine, where Victor Hugo's grandfather was a wood merchant. Léopold enlisted in the army of Revolutionary France at fourteen. He was an atheist and an ardent supporter of the Republic. Victor's mother Sophie was loyal to the deposed dynasty but would declare her children to be Protestants.[2][3][4] They met in Châteaubriant in 1796 and married the following year.[5]

Since Hugo's father was an officer in Napoleon's army, the family moved frequently from posting to posting. Léopold Hugo wrote to his son that he had been conceived on one of the highest peaks in the Vosges Mountains, on a journey from Lunéville to Besançon. "This elevated origin," he went on, "seems to have had effects on you so that your muse is now continually sublime."[6] Hugo believed himself to have been conceived on 24 June 1801, which is the origin of Jean Valjean's prisoner number 24601.[7]

In 1810, Hugo's father was made Count Hugo de Cogolludo y Sigüenza by then King of Spain Joseph Bonaparte,[8] though it seems that the Spanish title was not legally recognized in France. Hugo later titled himself as a viscount, and it was as "Vicomte Victor Hugo" that he was appointed a peer of France on 13 April 1845.[9][10]

Weary of the constant moving required by military life, Sophie separated temporarily from Léopold and settled in Paris in 1803 with her sons. There, she began seeing General Victor Fanneau de La Horie, Hugo's godfather, who had been a comrade of General Hugo's during the campaign in Vendee. In October 1807, the family rejoined Leopold, now Colonel Hugo, Governor of the province of Avellino. There, Victor was taught mathematics by Giuseppe de Samuele Cagnazzi, elder brother of Italian scientist Luca de Samuele Cagnazzi.[11] Sophie found out that Leopold had been living in secret with an Englishwoman called Catherine Thomas.[12]

- Sophie Trébuchet, mother of Victor Hugo

-

- General Joseph-Leopold Hugo, father of Victor Hugo

Soon Hugo's father was called to Spain to fight the Peninsular War. Madame Hugo and her children were sent back to Paris in 1808, where they moved to an old convent, 12 Impasse des Feuillantines, an isolated mansion in a deserted quarter of the left bank of the Seine. Hiding in a chapel at the back of the garden was de La Horie, who had conspired to restore the Bourbons and been condemned to death a few years earlier. He became a mentor to Victor and his brothers.[13]

In 1811 the family joined their father in Spain. Victor and his brothers were sent to school in Madrid at the Real Colegio de San Antonio de Abad while Sophie returned to Paris on her own, now officially separated from her husband. In 1812 de La Horie was arrested and executed. In February 1815 Victor and Eugene were taken away from their mother and placed by their father in the Pension Cordier, a private boarding school in Paris, where Victor and Eugène remained for three years while also attending lectures at Lycée Louis le Grand.[14] Hugo by Jean Alaux, 1825

Hugo by Jean Alaux, 1825

On 10 July 1816, Hugo wrote in his diary: "I shall be Chateaubriand or nothing." In 1817 he wrote a poem for a competition organised by the Academie Française, for which he received an honorable mention. The Academicians refused to believe that he was only fifteen.[15] Victor moved in with his mother to 18 rue des Petits-Augustins the following year and began attending law school. Victor fell in love and secretly became engaged, against his mother's wishes, to his childhood friend Adèle Foucher. In June 1821 Sophie Trebuchet died, and Léopold married his long-time mistress Catherine Thomas a month later. Victor married Adèle the following year. In 1819, Victor and his brothers began publishing a periodical called Le Conservateur littéraire.[16]

Career[edit]

Hugo published his first novel (Hans of Iceland, 1823) the year following his marriage, and his second three years later (Bug-Jargal, 1826). Between 1829 and 1840, he published five more volumes of poetry: Les Orientales, 1829; Les Feuilles d'automne, 1831; Les Chants du crépuscule [fr], 1835; Les Voix intérieures, 1837; and Les Rayons et les Ombres, 1840. This cemented his reputation as one of the greatest elegiac and lyric poets of his time.

Like many young writers of his generation, Hugo was profoundly influenced by François-René de Chateaubriand, the famous figure in the literary movement of Romanticism and France's pre-eminent literary figure during the early 19th century. In his youth, Hugo resolved to be "Chateaubriand or nothing", and his life would come to parallel that of his predecessor in many ways. Like Chateaubriand, Hugo furthered the cause of Romanticism, became involved in politics (though mostly as a champion of Republicanism), and was forced into exile due to his political stances. Along with Chateaubriand he attended the Coronation of Charles X in Reims in 1825.[17]

The precocious passion and eloquence of Hugo's early work brought success and fame at an early age. His first collection of poetry (Odes et poésies diverses) was published in 1822 when he was only 20 years old and earned him a royal pension from Louis XVIII. Though the poems were admired for their spontaneous fervor and fluency, the collection that followed four years later in 1826 (Odes et Ballades) revealed Hugo to be a great poet, a natural master of lyric and creative song. Victor Hugo in 1829, lithograph by Achille Devéria in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Victor Hugo in 1829, lithograph by Achille Devéria in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Jean Valjean (also known as Monsieur Madeleine in the book)[18] is the principal character in Hugo's great novel, Les Misérables.

Jean Valjean (also known as Monsieur Madeleine in the book)[18] is the principal character in Hugo's great novel, Les Misérables.

Victor Hugo's first mature work of fiction was published in February 1829 by Charles Gosselin without the author's name and reflected the acute social conscience that would infuse his later work. Le Dernier jour d'un condamné (The Last Day of a Condemned Man) would have a profound influence on later writers such as Albert Camus, Charles Dickens, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Claude Gueux, a documentary short story about a real-life murderer who had been executed in France, was published in 1834. Hugo himself later considered it to be a precursor to his great work on social injustice, Les Misérables.

Hugo became the figurehead of the Romantic literary movement with the plays Cromwell (1827) and Hernani (1830).[19] Hernani announced the arrival of French romanticism: performed at the Comédie-Française, it was greeted with several nights of rioting as romantics and traditionalists clashed over the play's deliberate disregard for neo-classical rules. Hugo's popularity as a playwright grew with subsequent plays, such as Marion Delorme (1831), Le roi s'amuse (1832), and Ruy Blas (1838).[20] Hugo's novel Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame) was published in 1831 and quickly translated into other languages across Europe. One of the effects of the novel was to shame the City of Paris into restoring the much neglected Cathedral of Notre Dame, which was attracting thousands of tourists who had read the popular novel.

Hugo began planning a major novel about social misery and injustice as early as the 1830s, but a full 17 years were needed for Les Misérables to be realised and finally published in 1862. Hugo had previously used the departure of prisoners for the Bagne of Toulon in Le Dernier Jour d'un condamné. He went to Toulon to visit the Bagne in 1839 and took extensive notes, though he did not start writing the book until 1845. On one of the pages of his notes about the prison, he wrote in large block letters a possible name for his hero: "JEAN TRÉJEAN". When the book was finally written, Tréjean became Jean Valjean.[21]

Hugo was acutely aware of the quality of the novel, as evidenced in a letter he wrote to his publisher, Albert Lacroix, on 23 March 1862: "My conviction is that this book is going to be one of the peaks, if not the crowning point of my work."[22] Publication of Les Misérables went to the highest bidder. The Belgian publishing house Lacroix and Verboeckhoven undertook a marketing campaign unusual for the time, issuing press releases about the work a full six months before the launch. It also initially published only the first part of the novel ("Fantine"), which was launched simultaneously in major cities. Installments of the book sold out within hours and had an enormous impact on French society. Illustration by Émile Bayard from the original edition of Les Misérables (1862)

Illustration by Émile Bayard from the original edition of Les Misérables (1862) Illustration by Luc-Olivier Merson for Notre-Dame de Paris (1881)

Illustration by Luc-Olivier Merson for Notre-Dame de Paris (1881)

The critical establishment was generally hostile to the novel; Taine found it insincere, Barbey d'Aurevilly complained of its vulgarity, Gustave Flaubert found within it "neither truth nor greatness", the Goncourt brothers lambasted its artificiality, and Baudelaire—despite giving favourable reviews in newspapers—castigated it in private as "repulsive and inept". However, Les Misérables proved popular enough with the masses that the issues it highlighted were soon on the agenda of the National Assembly of France. Today, the novel remains his best-known work. It is popular worldwide and has been adapted for cinema, television, and stage shows.

An apocryphal tale[23] has circulated, describing the shortest correspondence in history as having been between Hugo and his publisher Hurst and Blackett in 1862. Hugo was on vacation when Les Misérables was published. He queried the reaction to the work by sending a single-character telegram to his publisher, asking ?. The publisher replied with a single ! to indicate its success.[24] Hugo turned away from social/political issues in his next novel, Les Travailleurs de la Mer (Toilers of the Sea), published in 1866. The book was well received, perhaps due to the previous success of Les Misérables. Dedicated to the channel island of Guernsey, where Hugo spent 15 years of exile, the novel tells of a man who attempts to win the approval of his beloved's father by rescuing his ship, intentionally marooned by its captain who hopes to escape with a treasure of money it is transporting, through an exhausting battle of human engineering against the force of the sea and an almost mythical beast of the sea, a giant squid. Superficially an adventure, one of Hugo's biographers calls it a "metaphor for the 19th century–technical progress, creative genius and hard work overcoming the immanent evil of the material world."[25]

The word used in Guernsey to refer to squid (pieuvre, also sometimes applied to octopus) was to enter the French language as a result of its use in the book. Hugo returned to political and social issues in his next novel, L'Homme Qui Rit (The Man Who Laughs), which was published in 1869 and painted a critical picture of the aristocracy. The novel was not as successful as his previous efforts, and Hugo himself began to comment on the growing distance between himself and literary contemporaries such as Flaubert and Émile Zola, whose realist and naturalist novels were now exceeding the popularity of his own work.

His last novel, Quatre-vingt-treize (Ninety-Three), published in 1874, dealt with a subject that Hugo had previously avoided: the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. Though Hugo's popularity was on the decline at the time of its publication, many now consider Ninety-Three to be a work on par with Hugo's better-known novels.

Political life and exile[edit]

After three unsuccessful attempts, Hugo was finally elected to the Académie française in 1841, solidifying his position in the world of French arts and letters. A group of French academicians, particularly Étienne de Jouy, were fighting against the "romantic evolution" and had managed to delay Victor Hugo's election.[26] Thereafter, he became increasingly involved in French politics.

On the nomination of King Louis-Philippe, Hugo entered the Upper Chamber of Parliament as a pair de France in 1845, where he spoke against the death penalty and social injustice, and in favour of freedom of the press and self-government for Poland.

In 1848, Hugo was elected to the National Assembly of the Second Republic as a conservative. In 1849, he broke with the conservatives when he gave a noted speech calling for the end of misery and poverty. Other speeches called for universal suffrage and free education for all children. Hugo's advocacy to abolish the death penalty was renowned internationally.[note 1] Among the Rocks in Jersey (1853–1855)

Among the Rocks in Jersey (1853–1855)

When Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III) seized complete power in 1851, establishing an anti-parliamentary constitution, Hugo openly declared him a traitor to France. He moved to Brussels, then Jersey, from which he was expelled for supporting a Jersey newspaper that had criticised Queen Victoria. He finally settled with his family at Hauteville House in Saint Peter Port, Guernsey, where he would live in exile from October 1855 until 1870.

While in exile, Hugo published his famous political pamphlets against Napoleon III, Napoléon le Petit and Histoire d'un crime. The pamphlets were banned in France but nonetheless had a strong impact there. He also composed or published some of his best work during his period in Guernsey, including Les Misérables, and three widely praised collections of poetry (Les Châtiments, 1853; Les Contemplations, 1856; and La Légende des siècles, 1859).

However, Víctor Hugo said in Les Misérables:[28]

The wretched moral character of Thénardier, the frustrated bourgeois, was hopeless; it was in America what it had been in Europe. Contact with a wicked man is sometimes enough to rot a good deed and cause something bad to come out of it. With Marius's money, Thénardier became a slave trader.

Like most of his contemporaries, Hugo justified colonialism in terms of a civilizing mission and putting an end to the slave trade on the Barbary coast. In a speech delivered on 18 May 1879, during a banquet to celebrate the abolition of slavery, in the presence of the French abolitionist writer and parliamentarian Victor Schœlcher, Hugo declared that the Mediterranean Sea formed a natural divide between "ultimate civilisation and ... utter barbarism," adding, "God offers Africa to Europe. Take it", to civilise its indigenous inhabitants.

This might partly explain why in spite of his deep interest and involvement in political matters he remained silent on the Algerian issue. He knew about the atrocities committed by the French Army during the French conquest of Algeria as evidenced by his diary[29] but he never denounced them publicly; however, in Les Misérables, Hugo wrote: "Algeria too harshly conquered, and, as in the case of India by the English, with more barbarism than civilization."[30] Victor Hugo in 1861

Victor Hugo in 1861

After coming in contact with Victor Schœlcher, a writer who fought for the abolition of slavery and French colonialism in the Caribbean, he started strongly campaigning against slavery. In a letter to American abolitionist Maria Weston Chapman, on 6 July 1851, Hugo wrote: "Slavery in the United States! It is the duty of this republic to set such a bad example no longer.... The United States must renounce slavery, or they must renounce liberty."[31] In 1859, he wrote a letter asking the United States government, for the sake of their own reputation in the future, to spare abolitionist John Brown's life, Hugo justified Brown's actions by these words: "Assuredly, if insurrection is ever a sacred duty, it must be when it is directed against Slavery."[32] Hugo agreed to diffuse and sell one of his best known drawings, "Le Pendu", an homage to John Brown, so one could "keep alive in souls the memory of this liberator of our black brothers, of this heroic martyr John Brown, who died for Christ just as Christ.[33]

Only one slave on Earth is enough to dishonour the freedom of all men. So the abolition of slavery is, at this hour, the supreme goal of the thinkers.

— Victor Hugo, 17 January 1862, [34]

As a novelist, diarist, and member of Parliament, Victor Hugo fought a lifelong battle for the abolition of the death penalty. The Last Day of a Condemned Man published in 1829 analyses the pangs of a man awaiting execution; several entries in Things Seen (Choses vues), the diary he kept between 1830 and 1885, convey his firm condemnation of what he regarded as a barbaric sentence;[35] on 15 September 1848, seven months after the Revolution of 1848, he delivered a speech before the Assembly and concluded, "You have overthrown the throne. ... Now overthrow the scaffold."[36] His influence was credited in the removal of the death penalty from the constitutions of Geneva, Portugal, and Colombia.[37] He had also pleaded for Benito Juárez to spare the recently captured emperor Maximilian I of Mexico, but to no avail.[38]

Although Napoleon III granted an amnesty to all political exiles in 1859, Hugo declined, as it meant he would have to curtail his criticisms of the government. It was only after Napoleon III fell from power and the Third Republic was proclaimed that Hugo finally returned to his homeland in 1870, where he was promptly elected to the National Assembly and the Senate.

He was in Paris during the siege by the Prussian Army in 1870, famously eating animals given to him by the Paris Zoo. As the siege continued, and food became ever more scarce, he wrote in his diary that he was reduced to "eating the unknown".[39] Communards defending a barricade on the Rue de Rivoli

Communards defending a barricade on the Rue de Rivoli

During the Paris Commune—the revolutionary government that took power on 18 March 1871 and was toppled on 28 May—Victor Hugo was harshly critical of the atrocities committed on both sides. On 9 April, he wrote in his diary, "In short, this Commune is as idiotic as the National Assembly is ferocious. From both sides, folly."[40] Yet he made a point of offering his support to members of the Commune subjected to brutal repression. He had been in Brussels since 22 March 1871 when in the 27 May issue of the Belgian newspaper l’Indépendance Victor Hugo denounced the government's refusal to grant political asylum to the Communards threatened with imprisonment, banishment or execution.[41] This caused so much uproar that in the evening a mob of fifty to sixty men attempted to force their way into the writer's house shouting, "Death to Victor Hugo! Hang him! Death to the scoundrel!"[42]

Hugo, who said "A war between Europeans is a civil war,"[43] was an enthusiastic advocate for the creation of the United States of Europe. He expounded his views on the subject in a speech he delivered during the International Peace Congress which took place in Paris in 1849. The Congress, of which Hugo was the president, proved to be an international success, attracting such famous philosophers as Frederic Bastiat, Charles Gilpin, Richard Cobden, and Henry Richard. The conference helped establish Hugo as a prominent public speaker and sparked his international fame, and promoted the idea of the "United States of Europe".[44] On 14 July 1870 he planted the "oak of the United States of Europe" in the garden of Hauteville House where he stayed during his exile on Guernsey from 1856 to 1870. The massacres of Balkan Christians by the Turks in 1876 inspired him to write Pour la Serbie (For Serbia) in his sons' newspaper Le Rappel. This speech is today considered one of the founding acts of the European ideal.[45]

Because of his concern for the rights of artists and copyright, he was a founding member of the Association Littéraire et Artistique Internationale, which led to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works. However, in Pauvert's published archives, he states strongly that "any work of art has two authors: the people who confusingly feel something, a creator who translates these feelings, and the people again who consecrate his vision of that feeling. When one of the authors dies, the rights should totally be granted back to the other, the people." He was one of the earlier supporters of the concept of domaine public payant, under which a nominal fee would be charged for copying or performing works in the public domain, and this would go into a common fund dedicated to helping artists, especially young people.

Religious views[edit]

Head of Victor Hugo modeled by the sculptor Auguste Rodin and conserved at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen

Head of Victor Hugo modeled by the sculptor Auguste Rodin and conserved at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen

Hugo's religious views changed radically over the course of his life. In his youth and under the influence of his mother, he identified as a Catholic and professed respect for Church hierarchy and authority. From there he became a non-practising Catholic and increasingly expressed anti-Catholic and anti-clerical views. He frequented spiritism during his exile (where he participated also in many séances conducted by Madame Delphine de Girardin)[46][47] and in later years settled into a rationalist deism similar to that espoused by Voltaire. A census-taker asked Hugo in 1872 if he was a Catholic, and he replied, "No. A Freethinker."[48]

After 1872, Hugo never lost his antipathy towards the Catholic Church. He felt the Church was indifferent to the plight of the working class under the oppression of the monarchy. Perhaps he also was upset by the frequency with which his work appeared on the Church's list of banned books. Hugo counted 740 attacks on Les Misérables in the Catholic press.[49] When Hugo's sons Charles and François-Victor died, he insisted that they be buried without a crucifix or priest. In his will, he made the same stipulation about his own death and funeral.[50]

Yet he believed in life after death and prayed every single morning and night, convinced as he wrote in The Man Who Laughs that "Thanksgiving has wings and flies to its right destination. Your prayer knows its way better than you do."[51]

Hugo's rationalism can be found in poems such as Torquemada (1869, about religious fanaticism), The Pope (1878, anti-clerical), Religions and Religion (1880, denying the usefulness of churches) and, published posthumously, The End of Satan and God (1886 and 1891 respectively, in which he represents Christianity as a griffin and rationalism as an angel). 'The Hunchback of Notre-Dame' also garnered attention due to its portrayal of the abuse of power by the church, even getting listed as one of the 'forbidden books' by it. In fact, earlier adaptations had to change the villain, Claude Frollo from being a priest to avoid backlash.[52]

Vincent van Gogh ascribed the saying "Religions pass away, but God remains," actually by Jules Michelet, to Hugo.[53]

![[ℕ𝕖𝕧𝕖𝕣] 𝕊𝕖𝕝𝕝 𝕐𝕠𝕦𝕣 𝔹𝕚𝕥𝕔𝕠𝕚𝕟 - 📈ALT season 40% vs No ALT season 60%📉](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/d2fb6be9-79f1-42ad-b3c2-b55996aa9941/1)