Astrology22

Modern

Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther denounced astrology in his Table Talk. He asked why twins like Esau and Jacob had two different natures yet were born at the same time. Luther also compared astrologers to those who say their dice will always land on a certain number. Although the dice may roll on the number a couple of times, the predictor is silent for all the times the dice fails to land on that number.[115]

What is done by God, ought not to be ascribed to the stars. The upright and true Christian religion opposes and confutes all such fables.[115]

— Martin Luther, Table Talk

The Catechism of the Catholic Church maintains that divination, including predictive astrology, is incompatible with modern Catholic beliefs[116] such as free will:[110]

All forms of divination are to be rejected: recourse to Satan or demons, conjuring up the dead or other practices falsely supposed to "unveil" the future. Consulting horoscopes, astrology, palm reading, interpretation of omens and lots, the phenomena of clairvoyance, and recourse to mediums all conceal a desire for power over time, history, and, in the last analysis, other human beings, as well as a wish to conciliate hidden powers. They contradict the honor, respect, and loving fear that we owe to God alone.[117]

— Catechism of the Catholic Church

Scientific analysis and criticism

Main article: Astrology and science

Part of a series on theParanormalhide

Main articles

- Astral projectionAstrologyAuraBilocationBreatharianismClairvoyanceClose encounterCold spotCrystal gazingConjurationCryptozoologyDemonic possessionDemonologyEctoplasmElectronic voice phenomenonExorcismExtrasensory perceptionForteanaFortune-tellingGhost huntingIndigo childrenMagicMediumshipMiracleOccultOrbOuijaParanormal fictionParanormal televisionPrecognitionPreternaturalPsychicPsychic readingPsychometryReincarnationRemote viewingRetrocognitionSpirit photographySpirit possessionSpirit worldSpiritualismStone TapeSupernaturalTelekinesisTelepathyTable-turningUfology

Reportedly haunted locations:

show

Skepticism

show

Parapsychology

show

Related

vte Popper proposed falsifiability as something that distinguishes science from non-science, using astrology as the example of an idea that has not dealt with falsification during experiment.

Popper proposed falsifiability as something that distinguishes science from non-science, using astrology as the example of an idea that has not dealt with falsification during experiment.

The scientific community rejects astrology as having no explanatory power for describing the universe, and considers it a pseudoscience.[118][119][120]: 1350 Scientific testing of astrology has been conducted, and no evidence has been found to support any of the premises or purported effects outlined in astrological traditions.[15]: 424 [121][122] There is no proposed mechanism of action by which the positions and motions of stars and planets could affect people and events on Earth that does not contradict basic and well understood aspects of biology and physics.[12]: 249 [13] Those who have faith in astrology have been characterised by scientists including Bart J. Bok as doing so "...in spite of the fact that there is no verified scientific basis for their beliefs, and indeed that there is strong evidence to the contrary".[123]

Confirmation bias is a form of cognitive bias, a psychological factor that contributes to belief in astrology.[124]: 344, [125]: 180–181, [126]: 42–48 [a][127]: 553 Astrology believers tend to selectively remember predictions that turn out to be true, and do not remember those that turn out false. Another, separate, form of confirmation bias also plays a role, where believers often fail to distinguish between messages that demonstrate special ability and those that do not.[125]: 180–181 Thus there are two distinct forms of confirmation bias that are under study with respect to astrological belief.[125]: 180–181

Demarcation

Under the criterion of falsifiability, first proposed by the philosopher of science Karl Popper, astrology is a pseudoscience.[128] Popper regarded astrology as "pseudo-empirical" in that "it appeals to observation and experiment," but "nevertheless does not come up to scientific standards."[129] In contrast to scientific disciplines, astrology has not responded to falsification through experiment.[130]: 206

In contrast to Popper, the philosopher Thomas Kuhn argued that it was not lack of falsifiability that makes astrology unscientific, but rather that the process and concepts of astrology are non-empirical.[131]: 401 Kuhn thought that, though astrologers had, historically, made predictions that categorically failed, this in itself does not make astrology unscientific, nor do attempts by astrologers to explain away failures by claiming that creating a horoscope is very difficult. Rather, in Kuhn's eyes, astrology is not science because it was always more akin to medieval medicine; astrologers followed a sequence of rules and guidelines for a seemingly necessary field with known shortcomings, but they did no research because the fields are not amenable to research,[132]: 8 and so "they had no puzzles to solve and therefore no science to practise."[131]: 401, [132]: 8 While an astronomer could correct for failure, an astrologer could not. An astrologer could only explain away failure but could not revise the astrological hypothesis in a meaningful way. As such, to Kuhn, even if the stars could influence the path of humans through life, astrology is not scientific.[132]: 8

The philosopher Paul Thagard asserts that astrology cannot be regarded as falsified in this sense until it has been replaced with a successor. In the case of predicting behaviour, psychology is the alternative.[5]: 228 To Thagard a further criterion of demarcation of science from pseudoscience is that the state-of-the-art must progress and that the community of researchers should be attempting to compare the current theory to alternatives, and not be "selective in considering confirmations and disconfirmations."[5]: 227–228 Progress is defined here as explaining new phenomena and solving existing problems, yet astrology has failed to progress having only changed little in nearly 2000 years.[5]: 228 [133]: 549 To Thagard, astrologers are acting as though engaged in normal science believing that the foundations of astrology were well established despite the "many unsolved problems", and in the face of better alternative theories (psychology). For these reasons Thagard views astrology as pseudoscience.[5][133]: 228

For the philosopher Edward W. James, astrology is irrational not because of the numerous problems with mechanisms and falsification due to experiments, but because an analysis of the astrological literature shows that it is infused with fallacious logic and poor reasoning.[134]: 34

What if throughout astrological writings we meet little appreciation of coherence, blatant insensitivity to evidence, no sense of a hierarchy of reasons, slight command over the contextual force of critieria, stubborn unwillingness to pursue an argument where it leads, stark naivete concerning the efficacy of explanation and so on? In that case, I think, we are perfectly justified in rejecting astrology as irrational. ... Astrology simply fails to meet the multifarious demands of legitimate reasoning.

— Edward W. James[134]: 34

Effectiveness

Astrology has not demonstrated its effectiveness in controlled studies and has no scientific validity.[8]: 85, [15] Where it has made falsifiable predictions under controlled conditions, they have been falsified.[15]: 424 One famous experiment included 28 astrologers who were asked to match over a hundred natal charts to psychological profiles generated by the California Psychological Inventory (CPI) questionnaire.[135][136] The double-blind experimental protocol used in this study was agreed upon by a group of physicists and a group of astrologers[15] nominated by the National Council for Geocosmic Research, who advised the experimenters, helped ensure that the test was fair[14]: 420, [136]: 117 and helped draw the central proposition of natal astrology to be tested.[14]: 419 They also chose 26 out of the 28 astrologers for the tests (two more volunteered afterwards).[14]: 420 The study, published in Nature in 1985, found that predictions based on natal astrology were no better than chance, and that the testing "...clearly refutes the astrological hypothesis."[14]

In 1955, the astrologer and psychologist Michel Gauquelin stated that though he had failed to find evidence that supported indicators like zodiacal signs and planetary aspects in astrology, he did find positive correlations between the diurnal positions of some planets and success in professions that astrology traditionally associates with those planets.[137][138] The best-known of Gauquelin's findings is based on the positions of Mars in the natal charts of successful athletes and became known as the Mars effect.[139]: 213 A study conducted by seven French scientists attempted to replicate the claim, but found no statistical evidence.[139]: 213–214 They attributed the effect to selective bias on Gauquelin's part, accusing him of attempting to persuade them to add or delete names from their study.[140]

Geoffrey Dean has suggested that the effect may be caused by self-reporting of birth dates by parents rather than any issue with the study by Gauquelin. The suggestion is that a small subset of the parents may have had changed birth times to be consistent with better astrological charts for a related profession. The number of births under astrologically undesirable conditions was also lower, indicating that parents choose dates and times to suit their beliefs. The sample group was taken from a time where belief in astrology was more common. Gauquelin had failed to find the Mars effect in more recent populations, where a nurse or doctor recorded the birth information.[136]: 116

Dean, a scientist and former astrologer, and psychologist Ivan Kelly conducted a large scale scientific test that involved more than one hundred cognitive, behavioural, physical, and other variables—but found no support for astrology.[141][142] Furthermore, a meta-analysis pooled 40 studies that involved 700 astrologers and over 1,000 birth charts. Ten of the tests—which involved 300 participants—had the astrologers pick the correct chart interpretation out of a number of others that were not the astrologically correct chart interpretation (usually three to five others). When date and other obvious clues were removed, no significant results suggested there was any preferred chart.[142]: 190

Lack of mechanisms and consistency

Testing the validity of astrology can be difficult, because there is no consensus amongst astrologers as to what astrology is or what it can predict.[8]: 83 Most professional astrologers are paid to predict the future or describe a person's personality and life, but most horoscopes only make vague untestable statements that can apply to almost anyone.[8][126]: 83

Many astrologers claim that astrology is scientific,[143] while some have proposed conventional causal agents such as electromagnetism and gravity.[143] Scientists reject these mechanisms as implausible[143] since, for example, the magnetic field, when measured from Earth, of a large but distant planet such as Jupiter is far smaller than that produced by ordinary household appliances.[144]

Western astrology has taken the earth's axial precession (also called precession of the equinoxes) into account since Ptolemy's Almagest, so the "first point of Aries", the start of the astrological year, continually moves against the background of the stars.[145] The tropical zodiac has no connection to the stars, and as long as no claims are made that the constellations themselves are in the associated sign, astrologers avoid the concept that precession seemingly moves the constellations.[146] Charpak and Broch, noting this, referred to astrology based on the tropical zodiac as being "...empty boxes that have nothing to do with anything and are devoid of any consistency or correspondence with the stars."[146] Sole use of the tropical zodiac is inconsistent with references made, by the same astrologers, to the Age of Aquarius, which depends on when the vernal point enters the constellation of Aquarius.[15]

Astrologers usually have only a small knowledge of astronomy, and often do not take into account basic principles—such as the precession of the equinoxes, which changes the position of the sun with time. They commented on the example of Élizabeth Teissier, who claimed that, "The sun ends up in the same place in the sky on the same date each year", as the basis for claims that two people with the same birthday, but a number of years apart, should be under the same planetary influence. Charpak and Broch noted that, "There is a difference of about twenty-two thousand miles between Earth's location on any specific date in two successive years", and that thus they should not be under the same influence according to astrology. Over a 40-year period there would be a difference greater than 780,000 miles.[146]

Reception in the social sciences

The general consensus of astronomers and other natural scientists is that astrology is a pseudoscience which carries no predictive capability, with many philosophers of science considering it a "paradigm or prime example of pseudoscience."[147] Some scholars in the social sciences have cautioned against categorizing astrology, especially ancient astrology, as "just" a pseudoscience or projecting the distinction backwards into the past.[148] Thagard, while demarcating it as a pseudoscience, notes that astrology "should be judged as not pseudoscientific in classical or Renaissance times...Only when the historical and social aspects of science are neglected does it become plausible that pseudoscience is an unchanging category."[149] Historians of science such as Tamsyn Barton, Roger Beck, Francesca Rochberg, and Wouter J. Hanegraaff argue that such a wholesale description is anachronistic when applied to historical contexts, stressing that astrology was not pseudoscience before the 18th century and the importance of the discipline to the development of medieval science.[150][151][148][152][153] R. J. Hakinson writes in the context of Hellenistic astrology that "the belief in the possibility of [astrology] was, at least some of the time, the result of careful reflection on the nature and structure of the universe."[154]

Nicholas Campion, both an astrologer and academic historian of astrology, argues that Indigenous astronomy is largely used as a synonym for astrology in academia, and that modern Indian and Western astrology are better understood as modes of cultural astronomy or ethnoastronomy.[155] Roy Willis and Patrick Curry draw a distinction between propositional episteme and metaphoric metis in the ancient world, identifying astrology with the latter and noting that the central concern of astrology "is not knowledge (factual, let alone scientific) but wisdom (ethical, spiritual and pragmatic)".[156] Similarly, historian of science Justin Niermeier-Dohoney writes that astrology was "more than simply a science of prediction using the stars and comprised a vast body of beliefs, knowledge, and practices with the overarching theme of understanding the relationship between humanity and the rest of the cosmos through an interpretation of stellar, solar, lunar, and planetary movement." Scholars such as Assyriologist Matthew Rutz have begun using the term "astral knowledge" rather than astrology "to better describe a category of beliefs and practices much broader than the term 'astrology' can capture."[157][158]

Cultural impact

Western politics and society

In the West, political leaders have sometimes consulted astrologers. For example, the British intelligence agency MI5 employed Louis de Wohl as an astrologer after claims surfaced that Adolf Hitler used astrology to time his actions. The War Office was "...interested to know what Hitler's own astrologers would be telling him from week to week."[159] In fact, de Wohl's predictions were so inaccurate that he was soon labelled a "complete charlatan", and later evidence showed that Hitler considered astrology "complete nonsense".[160] After John Hinckley's attempted assassination of US President Ronald Reagan, first lady Nancy Reagan commissioned astrologer Joan Quigley to act as the secret White House astrologer. However, Quigley's role ended in 1988 when it became public through the memoirs of former chief of staff, Donald Regan.[161]

There was a boom in interest in astrology in the late 1960s. The sociologist Marcello Truzzi described three levels of involvement of "Astrology-believers" to account for its revived popularity in the face of scientific discrediting. He found that most astrology-believers did not claim it was a scientific explanation with predictive power. Instead, those superficially involved, knowing "next to nothing" about astrology's 'mechanics', read newspaper astrology columns, and could benefit from "tension-management of anxieties" and "a cognitive belief-system that transcends science."[162] Those at the second level usually had their horoscopes cast and sought advice and predictions. They were much younger than those at the first level, and could benefit from knowledge of the language of astrology and the resulting ability to belong to a coherent and exclusive group. Those at the third level were highly involved and usually cast horoscopes for themselves. Astrology provided this small minority of astrology-believers with a "meaningful view of their universe and [gave] them an understanding of their place in it."[b] This third group took astrology seriously, possibly as an overarching religious worldview (a sacred canopy, in Peter L. Berger's phrase), whereas the other two groups took it playfully and irreverently.[162]

In 1953, the sociologist Theodor W. Adorno conducted a study of the astrology column of a Los Angeles newspaper as part of a project examining mass culture in capitalist society.[163]: 326 Adorno believed that popular astrology, as a device, invariably leads to statements that encouraged conformity—and that astrologers who go against conformity, by discouraging performance at work etc., risk losing their jobs.[163]: 327 Adorno concluded that astrology is a large-scale manifestation of systematic irrationalism, where individuals are subtly led—through flattery and vague generalisations—to believe that the author of the column is addressing them directly.[164] Adorno drew a parallel with the phrase opium of the people, by Karl Marx, by commenting, "occultism is the metaphysic of the dopes."[163]: 329

A 2005 Gallup poll and a 2009 survey by the Pew Research Center reported that 25% of US adults believe in astrology,[165][166] while a 2018 Pew survey found a figure of 29%.[167] According to data released in the National Science Foundation's 2014 Science and Engineering Indicators study, "Fewer Americans rejected astrology in 2012 than in recent years."[168] The NSF study noted that in 2012, "slightly more than half of Americans said that astrology was 'not at all scientific,' whereas nearly two-thirds gave this response in 2010. The comparable percentage has not been this low since 1983."[168] Astrology apps became popular in the late 2010s, some receiving millions of dollars in Silicon Valley venture capital.[169]

India and Japan

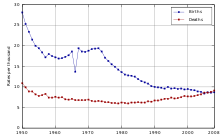

Birth (in blue) and death (in red) rates of Japan since 1950, with the sudden drop in births during hinoeuma year (1966)

Birth (in blue) and death (in red) rates of Japan since 1950, with the sudden drop in births during hinoeuma year (1966)

In India, there is a long-established and widespread belief in astrology. It is commonly used for daily life, particularly in matters concerning marriage and career, and makes extensive use of electional, horary and karmic astrology.[170][171] Indian politics have also been influenced by astrology.[172] It is still considered a branch of the Vedanga.[173][174] In 2001, Indian scientists and politicians debated and critiqued a proposal to use state money to fund research into astrology,[175] resulting in permission for Indian universities to offer courses in Vedic astrology.[176]

In February 2011, the Bombay High Court reaffirmed astrology's standing in India when it dismissed a case that challenged its status as a science.[177]

In Japan, strong belief in astrology has led to dramatic changes in the fertility rate and the number of abortions in the years of Fire Horse. Adherents believe that women born in hinoeuma years are unmarriageable and bring bad luck to their father or husband. In 1966, the number of babies born in Japan dropped by over 25% as parents tried to avoid the stigma of having a daughter born in the hinoeuma year.[178][179]

Literature and music

Title page of John Lyly's astrological play, The Woman in the Moon, 1597

Title page of John Lyly's astrological play, The Woman in the Moon, 1597

The fourteenth-century English poets John Gower and Geoffrey Chaucer both referred to astrology in their works, including Gower's Confessio Amantis and Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales.[180] Chaucer commented explicitly on astrology in his Treatise on the Astrolabe, demonstrating personal knowledge of one area, judicial astrology, with an account of how to find the ascendant or rising sign.[181]

In the fifteenth century, references to astrology, such as with similes, became "a matter of course" in English literature.[180] Title page of Calderón de la Barca's Astrologo Fingido, Madrid, 1641

Title page of Calderón de la Barca's Astrologo Fingido, Madrid, 1641

In the sixteenth century, John Lyly's 1597 play, The Woman in the Moon, is wholly motivated by astrology,[182] while Christopher Marlowe makes astrological references in his plays Doctor Faustus and Tamburlaine (both c. 1590),[182] and Sir Philip Sidney refers to astrology at least four times in his romance The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia (c. 1580).[182] Edmund Spenser uses astrology both decoratively and causally in his poetry, revealing "...unmistakably an abiding interest in the art, an interest shared by a large number of his contemporaries."[182] George Chapman's play, Byron's Conspiracy (1608), similarly uses astrology as a causal mechanism in the drama.[183] William Shakespeare's attitude towards astrology is unclear, with contradictory references in plays including King Lear, Antony and Cleopatra, and Richard II.[183] Shakespeare was familiar with astrology and made use of his knowledge of astrology in nearly every play he wrote,[183] assuming a basic familiarity with the subject in his commercial audience.[183] Outside theatre, the physician and mystic Robert Fludd practised astrology, as did the quack doctor Simon Forman.[183] In Elizabethan England, "The usual feeling about astrology ... [was] that it is the most useful of the sciences."[183]

In seventeenth century Spain, Lope de Vega, with a detailed knowledge of astronomy, wrote plays that ridicule astrology. In his pastoral romance La Arcadia (1598), it leads to absurdity; in his novela Guzman el Bravo (1624), he concludes that the stars were made for man, not man for the stars.[184] Calderón de la Barca wrote the 1641 comedy Astrologo Fingido (The Pretended Astrologer); the plot was borrowed by the French playwright Thomas Corneille for his 1651 comedy Feint Astrologue.[185]

Mars, the Bringer of War

Duration: 7 minutes and 58 seconds.

7:58

Venus, the Bringer of Peace

Duration: 8 minutes and 21 seconds.

8:21

Mercury, the Winged Messenger

Duration: 4 minutes and 24 seconds.

4:24

Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity

Duration: 8 minutes and 1 second.

8:01

Uranus, the Magician

Duration: 5 minutes and 20 seconds.

5:20

All performed by the US Air Force Band

Problems playing these files? See media help.

The most famous piece of music influenced by astrology is the orchestral suite The Planets. Written by the British composer Gustav Holst (1874–1934), and first performed in 1918, the framework of The Planets is based upon the astrological symbolism of the planets.[186] Each of the seven movements of the suite is based upon a different planet, though the movements are not in the order of the planets from the Sun. The composer Colin Matthews wrote an eighth movement entitled Pluto, the Renewer, first performed in 2000.[187] In 1937, another British composer, Constant Lambert, wrote a ballet on astrological themes, called Horoscope.[188] In 1974, the New Zealand composer Edwin Carr wrote The Twelve Signs: An Astrological Entertainment for orchestra without strings.[189] Camille Paglia acknowledges astrology as an influence on her work of literary criticism Sexual Personae (1990).[190]

Astrology features strongly in Eleanor Catton's The Luminaries, recipient of the 2013 Man Booker Prize.[191]

See also

- Astrology and science

- Astrology software

- Barnum effect

- List of astrological traditions, types, and systems

- List of topics characterised as pseudoscience

- Jewish astrology

- Scientific skepticism

Notes

- ^ see Heuristics in judgement and decision making

- ^ Italics in original.

References

- ^ * Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (2012). Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-521-19621-5. Archived from the original on 26 January 2023. Retrieved 19 July 2022.Long, H. S. (2003). "Astrology". In Carson, Thomas; Cerrito, Joann (eds.). New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Thomson/Gale. pp. 811–813. ISBN 0-7876-4005-0. p. 811.

- Thagard 1978, p. 229.

- ^ "astrology". Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ "astrology". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Inc. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ Bunnin, Nicholas; Yu, Jiyuan (2008). The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. p. 57. doi:10.1002/9780470996379. ISBN 9780470997215.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b c d e Thagard, Paul R. (1978). "Why Astrology is a Pseudoscience". Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association. 1 (1): 223–234. doi:10.1086/psaprocbienmeetp.1978.1.192639. S2CID 147050929. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Jarry, Jonathan (9 October 2020). "How Astrology Escaped the Pull of Science". Office for Science and Society. McGill University. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b Koch-Westenholz, Ulla (1995). Mesopotamian astrology: an introduction to Babylonian and Assyrian celestial divination. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. Foreword, 11. ISBN 978-87-7289-287-0.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b c d e Jeffrey Bennett; Megan Donohue; Nicholas Schneider; Mark Voit (2007). The cosmic perspective (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pearson/Addison-Wesley. pp. 82–84. ISBN 978-0-8053-9283-8.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b Kassell, Lauren (5 May 2010). "Stars, spirits, signs: towards a history of astrology 1100–1800". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 41 (2): 67–69. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2010.04.001. PMID 20513617.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b c d Porter, Roy (2001). Enlightenment: Britain and the Creation of the Modern World. Penguin. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-14-025028-2. he did not even trouble readers with formal disproofs!

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b Rutkin, H. Darell (2006). "Astrology". In K. Park; L. Daston (eds.). Early Modern Science. The Cambridge History of Science. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. pp. 541–561. ISBN 0-521-57244-4. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2022. As is well known, astrology finally disappeared from the domain of legitimate natural knowledge during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, although the precise contours of this story remain obscure.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b Vishveshwara, C. V.; Biswas, S. K.; Mallik, D. C. V., eds. (1989). Cosmic Perspectives: Essays Dedicated to the Memory of M.K.V. Bappu (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-34354-1.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b Peter D. Asquith, ed. (1978). Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association, vol. 1 (PDF). Dordrecht: Reidel. ISBN 978-0-917586-05-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.; "Chapter 7: Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Understanding". science and engineering indicators 2006. National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2016. About three-fourths of Americans hold at least one pseudoscientific belief; i.e., they believed in at least 1 of the 10 survey items[29]"... " Those 10 items were extrasensory perception (ESP), that houses can be haunted, ghosts/that spirits of dead people can come back in certain places/situations, telepathy/communication between minds without using traditional senses, clairvoyance/the power of the mind to know the past and predict the future, astrology/that the position of the stars and planets can affect people's lives, that people can communicate mentally with someone who has died, witches, reincarnation/the rebirth of the soul in a new body after death, and channeling/allowing a "spirit-being" to temporarily assume control of a body.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b c d e Carlson, Shawn (1985). "A double-blind test of astrology" (PDF). Nature. 318 (6045): 419–425. Bibcode:1985Natur.318..419C. doi:10.1038/318419a0. S2CID 5135208. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b c d e f Zarka, Philippe (2011). "Astronomy and astrology". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 5 (S260): 420–425. Bibcode:2011IAUS..260..420Z. doi:10.1017/S1743921311002602. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b David E. Pingree; Robert Andrew Gilbert. "Astrology - Astrology in modern times". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 October 2012. In countries such as India, where only a small intellectual elite has been trained in Western physics, astrology manages to retain here and there its position among the sciences. Its continued legitimacy is demonstrated by the fact that some Indian universities offer advanced degrees in astrology. In the West, however, Newtonian physics and Enlightenment rationalism largely eradicated the widespread belief in astrology, yet Western astrology is far from dead, as demonstrated by the strong popular following it gained in the 1960s.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "astrology". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2011. Differentiation between astrology and astronomy began late 1400s and by 17c. this word was limited to "reading influences of the stars and their effects on human destiny."

- ^ "astrology, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Third ed.). Oxford University Press. December 2021. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2011. In medieval French, and likewise in Middle English, astronomie is attested earlier, and originally covered the whole semantic field of the study of celestial objects, including divination and predictions based on observations of celestial phenomena. In early use in French and English, astrologie is generally distinguished as the 'art' or practical application of astronomy to mundane affairs, but there is considerable semantic overlap between the two words (as also in other European languages). With the rise of modern science from the Renaissance onwards, the modern semantic distinction between astrology and astronomy gradually developed, and had become largely fixed by the 17th cent. [...] The word is not used by Shakespeare.

- ^ Rochberg, Francesca (1998). Babylonian Horoscopes. American Philosophical Society. pp. ix. ISBN 978-0-87169-881-0.

- ^ Campion, Nicholas (2009). History of western astrology. Volume II, The medieval and modern worlds (first ed.). Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-8129-9.

- ^ Jump up to:

- a b Marshack, Alexander (1991). The roots of civilization : the cognitive beginnings of man's first art, symbol and notation (Rev. and expanded ed.). Moyer Bell. ISBN 978-1-55921-041-6.

- ^ Evelyn-White, Hesiod; with an English translation by Hugh G. (1977). The Homeric hymns and Homerica (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 663–677. ISBN 978-0-674-99063-0. Fifty days after the solstice, when the season of wearisome heat is come to an end, is the right time to go sailing. Then you will not wreck your ship, nor will the sea destroy the sailors, unless Poseidon the Earth-Shaker be set upon it, or Zeus, the king of the deathless gods

- ^ Aveni, David H. Kelley, Eugene F. Milone (2005). Exploring ancient skies an encyclopedic survey of archaeoastronomy (Online ed.). New York: Springer. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-387-95310-6.

- ^ Russell Hobson, The Exact Transmission of Texts in the First Millennium B.C.E., Published PhD Thesis. Department of Hebrew, Biblical and Jewish Studies. University