Banking is Broken: How Blockchain Can Fix Bank Runs

Banking is Broken: How Blockchain Can Fix Bank Runs

Sherry Jiang

Bank runs are happening at unprecedented speeds. In just three days, we witnessed two of the largest bank failures in American history. Signature Bank, a New York-based regional bank, shuttered suddenly on Sunday, marking the third-biggest bank failure in U.S. history — just two days after the country’s second biggest failure, Silicon Valley Bank.

Despite this, there is a chorus of voices that want us to believe that all is fine in banking. “Americans can have confidence that the banking system is safe”, said Biden. “There is no systemic risk to our financial system”, said Britain’s Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt.

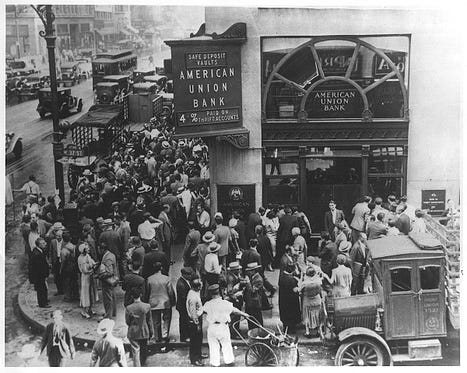

These reassurances are understandable, regardless of their believability. In 2014, rural banks in China’s eastern city of Yancheng stacked piles of cash in plain view behind teller windows to calm depositors queueing at bank branches for a third straight day — following rumors that they had run out of cash. American banking tycoons Marriner and George Eccles, did something similar during the Great Depression to fend off multiple bank runs.

But history has shown that some skepticism is warranted. “We believe the effect of the troubles in the subprime sector on the broader housing market will be limited and we do not expect significant spillovers from the subprime market to the rest of the economy or to the financial system,” declared Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke in May 2007 — just a year before the Global Financial Crisis — the worst banking crisis since the Great Depression.

While we may not see a wave of bank collapses like in 2008, the rapidity and scale of the run on both Signature and Silicon Valley Bank reveal deep structural flaws with the very design of fractional reserve banking in the internet age.

This is a story bigger than any one bank. Bigger than the failure of risk management. Bigger than economic vulnerability created by the aggressive seesawing between artificially high and low interest rates. It is a story of how fractional reserve banking is fundamentally broken and antiquated.

The big con: fractional reserve banking

There is a profound contradiction at the heart of fractional reserve banking. Deposits are liabilities of the bank that must be repaid on demand. But most of those deposits are being loaned out to earn an interest — and those loans have maturities that cannot be recalled on demand. The balance on your bank account statement is an illusion — it isn’t actually there.

Fragility is baked into the very nature of fractional reserve banking, because it creates liquid claims against illiquid assets. Put simply, at any given time banks never have enough money to fulfill their promise to repay all their depositors on demand.

The word “con”, is shorthand for a “confidence trick”. And although we are largely content to forget this inconvenient truth as we go about our daily lives, mere confidence is the cornerstone of banking today.

“The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve”, explained Satoshi Nakmoto in a forum post announcing the Bitcoin White Paper in September 2009.

For the uninitiated, this is not merely the fringe opinion of a techno-anarchist. “Under a fractional-reserve banking system (the system in operation virtually everywhere in modern developed economies), banks have to hold a fraction of their deposits (a liability for them) as deposits at the central bank (called reserves) (an asset for them), but they can “lend out” the remainder”, wrote Paul Sheard, Standard & Poor’s chief global economist.

One of the first modern scholarly analyses of this fundamental contradiction was a paper titled, “Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity,” written by Douglas W. Diamond and Philip H. Dybvig, published in the Journal of Political Economy in 1983.

Confidence in an internet age?

The fall of Silicon Valley Bank is being described as the fastest bank run in history. This is not a coincidence. The banking environment has changed dramatically, and the current fractional reserve banking is no longer compatible with the rapidity of information dissemination in modern society.

The reserve ratio was a concept first introduced in American banking in 1863 to protect depositor funds from being used by banks in risky investments. Federal deposit insurance was pioneered in America in 1934, in an effort to stop the rampant issue of bank runs. Yet, with each passing decade, the use of these tools appear increasingly inadequate to do their one job — prevent bank runs.

In the past, rumors spread by radio, newspapers and television. To demand for withdrawals, depositors had to physically queue and only during the opening hours of banks’ branches. In the internet age, rallies and crashes in financial markets are not only more extreme in magnitude, but also faster. The diffusion of information (reliable or not) spreads at the speed of a 140 character tweet. Furthermore, internet banking has also dramatically shortened the time it takes for depositors to demand withdrawals from troubled banks.

These concerns are not new. Industry observers have been sounding alarm bells as early as 2019. “A digital bank run in a hypothetical future would be much more dangerous as it would happen in seconds and minutes when clients could simply use mobile banking apps to transfer money to another account,” said Susanne Chishti, chief executive of Fintech Circle, in an interview given to Raconteur magazine.

Former Canadian central banker Mark Zelmer’s independent review into the UK’s Co-operative Bank, noted that Open Banking “may come at the cost of less stable deposit-taking institutions”. In the report, Zelmer concluded, saying, “I would not be surprised if smaller institutions find their deposit bases become less sticky over time and more likely to run at the first hint of trouble”.

This remark by Zelmer has now become a shocking reality just 4 years later. SVB, the 16th largest bank in America that has operated for 40 years, collapsed in just a mere 48 hours, when the first hint of trouble around its $1.8B losses on securities soon spread like wildfire over social media and online spaces:

Timeline of SVB’s collapse

- March 8, 2023: SVB announced that it would sell $2.25B of shares to fix its balance sheet. SVB suffered a $1.8B loss on the sale of long-term bonds, which were decimated in value when the Fed started hiking interest rates, and simultaneously experienced thinning deposits because many startups started withdrawing because of the current macro climate

- March 9, 2023: Shares of SVB plummeted 60%. SVB tries to calm venture capital investors, but Pandora’s box has already been opened. VCs urge their portfolio companies to pull funds from SVB, Slacks across startup and tech groups start lighting up, and Twitter grows in full force of FUD. “OK I am hearing from dozens of founders about what to do at SVB. It’s an all out bank run.” wrote Howard Lerman on Twitter.

- March 10, 2023: SVB collapsed, shares were halted, and regulators shut down operations.

In comparison, the previous banking crises of Northern Rock (2007), Bear Stearns (2008), and Home Capital Group (2017) all took place over the course of several months. Northern Rock first sought emergency funding from the Bank of England in September 2007, but didn’t ultimately become nationalized until February of 2008. Bear Stearns started struggling in 2007 when the housing bubble burst, but the rumors around its decline and ultimate shutdown did not come until March 2008.

In just 15 years, the time it took for a bank to collapse went from a few months to just a few days. This unprecedented speed of collapse coming from a digital bank run will not be just an anomaly. It will become the new normal.

Our current model of fractional reserve banking is ill-suited to our networked age. Liquidity crises can very quickly become solvency crises — all of which hangs on the confidence of depositors and investors.

Confidence, as we all know, is an incredibly fragile thing in an internet age. Yet, unbelievable as it may sound, it is in this increasingly frail house of cards, this dangerous con — that we are asked to store our entire life’s savings.

Better banking designs

The pursuit of more resilient alternatives to fractional reserve banking has been going on for decades. As early as 1933, a group of economists hatched an idea known as the “Chicago Plan”. They hoped to identify the causes of the Great Depression. Among the culprits they identified was fractional reserve banking.

Their solution? A 1:1 ratio of loans to reserves. The Chicago Plan would not only have subjected checking deposits to 100% reserves, but banks could no longer make loans out of savings deposits. To obtain the capital to make loans, they would have to raise money by equity-financed investment trusts.

Despite generating a lot of interest at the time, the plan fell into obscurity. It resurfaced briefly several years later, following the US recession of 1937–1938, and once more in the wake of the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis.

In March 2015, Iceland published the results of an intensive study that explored the viability of ending fractional reserve banking. The report, commissioned by the prime minister, explored alternatives to the fractional reserve system, including a revival of the Chicago Plan.

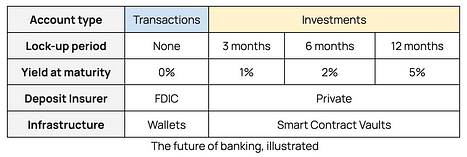

It proposed the separation of bank deposits into two types of accounts: (i) interest-free Transaction Accounts kept at the Central Bank, which are not available for banks to invest, and redeemable on demand, and (ii) yield-bearing Investment Accounts which are invested by the bank, and only redeemable at maturity, ranging from 45 days to a few years.

Funds can be transferred from a Transaction Account to an Investment Account. Banks can offer Investment Accounts with different risk profiles, maturity and interest rates, catering to different types of savers.

The Smart Contract Solution

Fractional reserve banking is a walking contradiction propped up by mere confidence. Confidence is increasingly fragile in an internet age where both the circulation of information, and the ability to act happens 24/7, at the speed of a click. Deposit insurance, and reserve ratios — the two primary tools developed to shore up confidence in fractional reserve banking are proving to be increasingly inadequate.

SVB and Signature weren’t the first, and certainly won’t be the last internet-fuelled bank run. There are two possible responses: (i) restrict deposit withdrawals in crises, (ii) restrict lending to prevent crises. The first two are highly unpalatable to depositors and banks respectively.

In every crisis from the Great Depression, to the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, to Silicon Valley bank — robust alternatives to fractional reserve banking have been proposed, but not implemented. Largely because private individuals lacked the tools to build alternatives to commercial banks, or central banks.

Today, the advent of DeFi and cryptocurrency has changed that. We now have in our hands, the tools to seize a historic opportunity to build an on-chain alternative to fractional reserve banking.

This is one example of how a design might work.

This design will eliminate the creation of liquid liability claims against illiquid assets, and prevent bank runs — without having to eliminate banks’ ability to make loans, or impose deposit withdrawal limits in times of crisis.

By separating liquid funds (e.g., “checking account”) that people use for transactions from funds people are willing to risk more for investments, this design provides transparency and assurances that people’s funds are actually safe being kept safe and not being commingled for other purposes. In addition, because liquid assets are being held in self-custody solutions like wallets, there is no need to have trust in another third party like a bank.

All of these features can be automated, and enforced via smart contracts. It removes the need for attestation or independent audits, and minimizes the difficulties of banking supervision and oversight.

Conclusion

What has occurred over the past week with Signature and SVB hopefully will spur a re-examination of our current banking system at a foundational level.

While on-chain finance and DeFi are still in their nascent stages in technology and economic design, they have the enormous potential to solve the deep structural issues of our banking system, and create a new one more compatible with our modern digital society.

![[LIVE] Engage2Earn: auspol follower rush](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/c1a761de-5ce9-4e9b-b5b3-dc009e60bfa8/1)

![[ℕ𝕖𝕧𝕖𝕣] 𝕊𝕖𝕝𝕝 𝕐𝕠𝕦𝕣 𝔹𝕚𝕥𝕔𝕠𝕚𝕟 - And Now What.... Pray To The God Of Hopium?](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/79e7827b-c644-4853-b048-a9601a8a8da7/1)