CAN'T OPEN APPS ON MACOS: AN OCSP DISASTER WAITING TO HAPPEN

macOS users experienced worrying hangs when opening applications not downloaded from the Mac App Store. Many users suspected hardware issues with their devices, but as they took to social media, they found it was a widespread problem. And it was no coincidence that it was happening so soon after the launch of macOS “Big Sur”.

Eventually, a tweet by Jeff Johnson pinpointed the underlying issue. Apple’s “OCSP Responder” service was overloaded, therefore macOS was unable to verify app developers’ cryptographic certificates. But why are OCSP Responders in the critical path of apps launching? This post will briefly discuss code signing, how Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) works, why it’s deeply flawed, and what are some better alternatives. Unlike other posts on this incident, I want to emphasise the practical crypto aspects (at a high level) and offer a balanced perspective.

But why are OCSP Responders in the critical path of apps launching? This post will briefly discuss code signing, how Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) works, why it’s deeply flawed, and what are some better alternatives. Unlike other posts on this incident, I want to emphasise the practical crypto aspects (at a high level) and offer a balanced perspective.

CODE SIGNING

On their developer portal, Apple explain the purpose of code signing:

Code signing your app assures users that it is from a known source and the app hasn’t been modified since it was last signed. Before your app can integrate app services, be installed on a device, or be submitted to the App Store, it must be signed with a certificate issued by Apple.

In other words, if developers want their apps to be trusted on macOS, they must sign them using their own certificate keypair. Keychain is used to generate a unique “Developer ID” certificate, which includes a private key for the developer to use, and a public key for distribution. After Apple have signed the Developer ID certificate, the developer can use the private key to produce cryptographic signatures on their apps as part of their release process.

When you run an app, its signature is verified against the public key of the developer’s certificate. Then, the certificate itself is verified, by checking that it hasn’t expired yet (certificates are typically valid for 1 year), and that it’s ultimately signed by Apple’s root certificate. There may also be intermediate certificates as part of the chain up to the root certificate. A “chain of trust” has been created, because the developer ID certificate signed an app, an intermediate certificate signed the developer ID certificate, and Apple’s root certificate signed the intermediate certificate. Any Apple device can verify this chain of trust and therefore approve an app to run.

This is similar to the TLS Public Key Infrastructure used on the internet. But it’s also fundamentally different since Apple has total control over its own chain of trust. Other certificate authorities are not allowed to issue valid certificates for code signing as all certificates must chain back up to Apple.

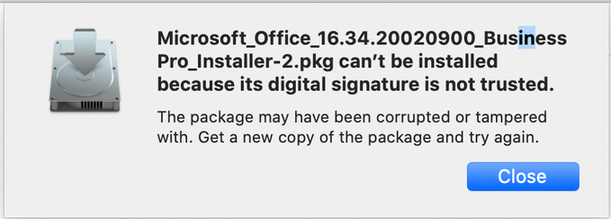

If the verification process wasn’t successful, then users will see a scary dialogue which is difficult to bypass:

REVOCATION

What happens when a developer is found to be breaching Apple’s rules, or loses control of their private key? A certificate authority needs to be able to instantly nullify bad certificates they’ve issued. If a certificate is being used maliciously, it’s not acceptable to wait days or months until it expires naturally, otherwise a leak of a high-profile private key would render the whole system useless.

This is where certificate revocation comes in. It’s an additional step in the signature verification process, which involves finding out from the certificate authority if a certificate is still valid.

Originally, at least on the web, this was done the simplest way you can imagine. The certificate authority would give you a Certificate Revocation List (CRL), containing serial numbers of all revoked certificates, and you could check the certificate you are currently verifying is not on the list. However, this approach stopped being used by web browsers since the list got longer and longer and failed to scale. Especially after terrifying exploits like Heartbleed demanded mass revocation of certificates.

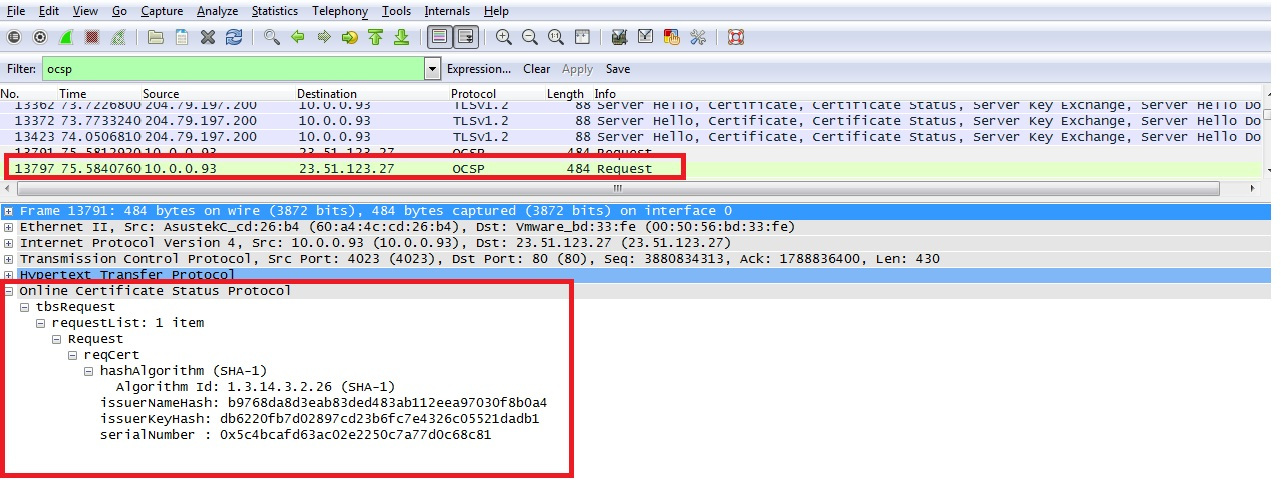

Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) is an alternative allowing real-time checking of certificates. Each certificate can include a baked-in “OCSP Responder”, a URL that you can query that will report whether the certificate has been revoked. In Apple’s case, that’s “ocsp.apple.com”. So now, in addition to verifying the cryptographic validity of the signature, each time you launch an app you’re performing a real-time check with Apple (subject to some caching) to ensure they still think the developer’s ID certificate is legitimate.

OCSP’S AVAILABILITY PROBLEM

There’s a huge problem with OCSP: it makes an external service a single point of failure. What happens if the OCSP Responder is down or unreachable? Do we just refuse to verify the certificate (hard-fail)? Or do we pretend that the check was successful (soft-fail)?

Apple are forced to use the soft-fail behaviour, otherwise apps wouldn’t work when you’re offline. As it happens, all major browsers also implement the soft-fail behaviour, since OCSP Responders have traditionally been unreliable, and browsers want to keep displaying websites even if certificate authorities’ responders are temporarily down.

But soft-fail isn’t great, because it means that an attacker with network control can block requests to the responder, and the revocation check will be skipped. In fact, that was the hotfix widely shared on Twitter during this incident: blackhole traffic to “ocsp.apple.com” by adding a line to /etc/hosts. A lot of people won’t be removing that line anytime soon, since disabling OCSP doesn’t cause any noticeable problems.

THE INCIDENT

If Apple’s OCSP check was built to soft-fail, then why did apps hang when the OCSP Responder was down? Probably because this was actually a different failure case: the OCSP Responder was not completely down, it was performing badly.

Due to the load added by millions of users worldwide upgrading to macOS “Big Sur”, Apple’s servers slowed to a crawl, and although they weren’t properly answering OCSP queries, they were working just enough that the soft-fail didn’t trigger.

OCSP’S PRIVACY PROBLEM

In addition to OCSP’s availability problems, the protocol wasn’t initially designed with privacy in mind. A basic OCSP query involves an unencrypted HTTP request to the OCSP Responder with the serial number of the certificate. Therefore not only can the responder figure out what certificate you are interested in, but so can your ISP and anybody else intercepting packets. Apple could use this to build a timeline of which developers’ apps you are opening, as could third parties. Adding encryption is possible, and there’s a better, more private version called OCSP stapling, but Apple is not using either of these things. In fact OSCP stapling wouldn’t make sense in this scenario, but it illustrates how OCSP needs improvements to not leak data by default.

Adding encryption is possible, and there’s a better, more private version called OCSP stapling, but Apple is not using either of these things. In fact OSCP stapling wouldn’t make sense in this scenario, but it illustrates how OCSP needs improvements to not leak data by default.

A BETTER FUTURE

This incident has started a lively debate in the software community, with one side proclaiming “Your Computer Isn’t Yours” and the other arguing that “application trust is hard but Apple does it well”. This post aims to show that whichever side you agree with, OCSP is a terrible way to manage certificate revocation, and will lead to more availability and privacy incidents in future. In my opinion, it was a poor engineering decision for Apple to make app launching dependent on OCSP. In the short term at least they have mitigated the damage by increasing the time that responses are cached.

Fortunately, a better revocation method is reaching maturity. CRLite is a way to shrink down lists of all revoked certificates to a reasonable size. Scott Helme’s blog gives a good summary of how CRLite uses Bloom Filters to make the Certificate Revocation List approach – which OCSP superseded – feasible again.

Theoretically, macOS devices could pull updates to this list periodically and do certificate revocation checking on the device itself, addressing the availability and privacy problems with OCSP. On the other hand, since the list of revoked Developer ID certificates is much smaller than the list of all revoked PKI certificates, it’s worth asking why Apple haven’t opted to use CRLs in the first place. Perhaps they don’t want to reveal any information about which certificates they’ve revoked.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the incident this week was a good time to reflect on the trust model that has been promoted by organisations like Apple and Microsoft. Malware has grown in sophistication and most people aren’t in a position to judge whether it’s safe to run particular binaries. Code signing seems like a neat way to leverage cryptography to determine whether or not to trust applications, and to at least associate apps with known developers. And revocation is a necessary part of maintaining that trust.

However, by adding several mundane failure modes to the verification process, OCSP spoils any cryptographic elegance the code signing and verifying process has. While OCSP is also widely used for TLS certificates on the internet, the large number of PKI certificate authorities and relaxed attitude of browsers means that failures are less catastrophic. Moreover, people are accustomed to seeing websites become unavailable from time to time, but they don’t expect the same from apps on their own devices. macOS users were alarmed at how their apps could become collateral damage for an infrastructure issue at Apple. Yet this was an inevitable outcome arising from the fact that certificate verification depends on external infrastructure, and no infrastructure is 100% reliable.

Scott Helme also has concerns about the power that Certificate Authorities gain when certification revocation actually works effectively. Even if you aren’t bothered about the potential for censorship, there will be occasional mistakes and these must be weighed against the security benefits. As one developer discovered when Apple mistakenly revoked his certificate, the risk of working within a locked down platform is that you may get locked out.

![[ℕ𝕖𝕧𝕖𝕣] 𝕊𝕖𝕝𝕝 𝕐𝕠𝕦𝕣 𝔹𝕚𝕥𝕔𝕠𝕚𝕟 - And Now What.... Pray To The God Of Hopium?](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/79e7827b-c644-4853-b048-a9601a8a8da7/1)