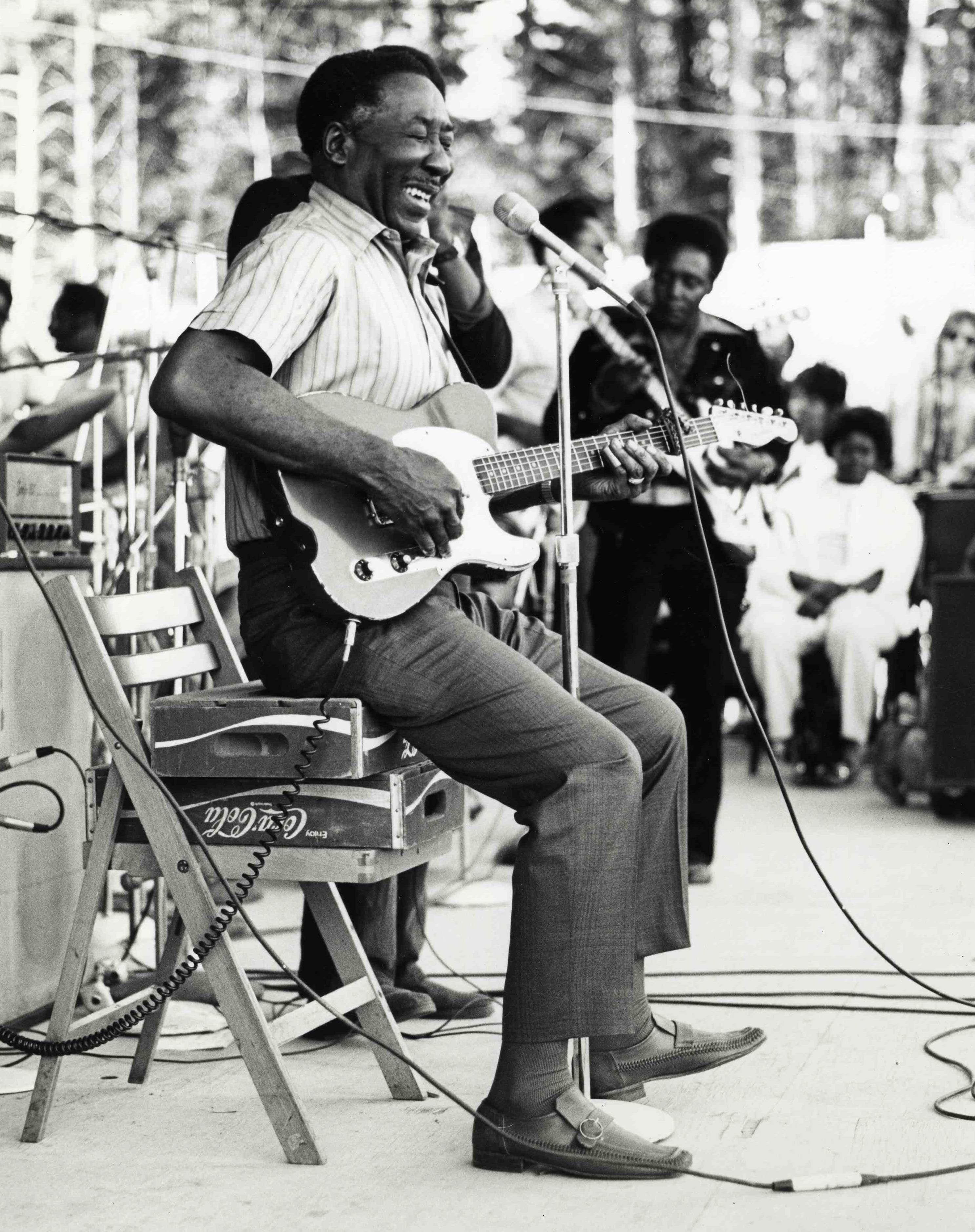

Muddy Waters

Muddy Waters

Muddy Waters, born McKinley Morganfield on April 4, 1913, and passing away on April 30, 1983, was a seminal figure in American blues. Often hailed as the "father of modern Chicago blues," Waters played a crucial role in shaping the post-World War II blues scene.

Raised on Stovall Plantation near Clarksdale, Mississippi, Muddy Waters discovered his passion for music at an early age. By 17, he was proficient in playing both the guitar and harmonica, drawing inspiration from local blues legends like Son House and Robert Johnson. In 1941, he was recorded in Mississippi by folklorist Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress.

In 1943, Waters made a significant move to Chicago to pursue a full-time career in music. There, he began recording for various labels, including Columbia Records and Aristocrat Records, founded by Leonard and Phil Chess.

During the early 1950s, Muddy Waters, along with his band featuring notable musicians like Little Walter Jacobs, Jimmy Rogers, Elga Edmonds (or Elgin Evans), and Otis Spann, recorded a series of blues classics. These recordings, often featuring collaborations with bassist and songwriter Willie Dixon, produced timeless tracks such as "Hoochie Coochie Man," "I Just Want to Make Love to You," and "I'm Ready."

In 1958, Waters made a significant impact overseas when he traveled to England, sparking a resurgence of interest in blues music in the country. His electrifying performance at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960 was captured and released as his first live album, titled "At Newport 1960."

Muddy Waters' profound influence extends beyond the blues genre, shaping the trajectory of American music, including rock and roll. His distinctive style and soulful performances continue to resonate with audiences worldwide, leaving an indelible mark on the history of music.

Muddy Waters' exact place and date of birth remain uncertain, with conflicting evidence suggesting different locations and years. While he claimed to have been born in Rolling Fork, Sharkey County, Mississippi, in 1915, other records suggest he might have been born in Jug's Corner, Issaquena County, in 1913. Documentation from the 1930s and 1940s, including his marriage license and musicians' union card, listed his birth year as 1913.

Raised by his grandmother, Della Grant, after his mother's death, Waters earned his nickname "Muddy" because of his fondness for playing in the muddy waters of Deer Creek. He later adopted the surname "Waters" as he became involved in music, particularly after taking up the harmonica in his early teens.

Waters' introduction to music began in church, where he sang as a Baptist. He bought his first guitar at 17, using money from selling his last horse. He started performing his songs in local venues, mainly on the plantation owned by Colonel William Howard Stovall.

The cabin where Waters lived during his youth on Stovall Plantation is now preserved at the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Mississippi. Despite the uncertainties surrounding his birth details, Muddy Waters' impact on blues music and his contributions to American culture remain undeniable.

In the early 1930s, Muddy Waters joined Big Joe Williams on tours of the Delta, playing harmonica. However, Williams eventually dropped Muddy from the lineup, reportedly because Muddy was attracting more female fans.

In August 1941, Alan Lomax, representing the Library of Congress, visited Stovall, Mississippi, to record various country blues musicians. Muddy Waters was one of them. Reflecting on this experience, Muddy expressed his exhilaration upon hearing his own voice played back to him on a recording. Lomax returned in July 1942 for another recording session with Muddy. These recordings, eventually released by Testament Records as "Down on Stovall's Plantation," captured the essence of Muddy's early blues style.

In 1943, Muddy made the pivotal decision to move to Chicago to pursue a full-time career in music. He considered this move the most significant event in his life. Initially, he worked odd jobs during the day and performed at night, living with a relative in Chicago. Big Bill Broonzy, a prominent bluesman at the time, provided Muddy with opportunities to open his shows, exposing him to larger audiences.

Muddy's sound evolved in Chicago, influenced by the electrified atmosphere of postwar African American culture. He bought his first electric guitar in 1944 and formed his first electric combo. This decision to electrify his sound was driven by the necessity to be heard in the noisy clubs of Chicago.

In 1946, Muddy recorded songs for Mayo Williams at Columbia Records, followed by recordings for Aristocrat Records, later renamed Chess Records. His hits like "I Can't Be Satisfied" and "I Feel Like Going Home" in 1948, along with his signature tune "Rollin' Stone," propelled him to fame and solidified his status as a pioneering figure in the blues scene.

The Chess brothers initially resisted Muddy Waters' desire to record with his working band in the studio. Instead, Muddy was provided with backing bassists like Ernest "Big" Crawford or other musicians assembled for the recording sessions, including "Baby Face" Leroy Foster and Johnny Jones. However, Chess eventually relented, and by September 1953, Muddy was recording with what became one of the most celebrated blues groups in history: Little Walter Jacobs on harmonica, Jimmy Rogers on guitar, Elga Edmonds (Elgin Evans) on drums, and Otis Spann on piano. Together, they recorded a series of blues classics during the early 1950s, often with the assistance of bassist and songwriter Willie Dixon. Songs like "Hoochie Coochie Man," "I Just Want to Make Love to You," and "I'm Ready" became cornerstones of Muddy Waters' repertoire.

Muddy Waters' band served as a breeding ground for some of Chicago's finest blues talents, with several members going on to successful solo careers. Little Walter departed in 1952 after his hit single "Juke" achieved success, although he maintained a collaborative relationship with Muddy. Howlin' Wolf's arrival in Chicago in 1954, fueled by his success with Chess Records, ignited a legendary rivalry with Muddy Waters, partly fueled by suspicion regarding Willie Dixon's songwriting contributions. In 1955, Jimmy Rogers left to focus exclusively on his own band, which had been a sideline until then.

Throughout the mid-1950s, Muddy Waters' singles frequently charted on Billboard magazine's Rhythm & Blues charts, with hits like "Sugar Sweet" in 1955 and "Trouble No More," "Forty Days and Forty Nights," and "Don't Go No Farther" in 1956. Although "Got My Mojo Working," released in 1956, didn't chart, it became one of his best-known songs. By the late 1950s, Muddy's singles success waned, with only "Close to You" reaching the charts in 1958. In the same year, Chess released his first compilation album, "The Best of Muddy Waters," which compiled twelve of his singles up to 1956.

Muddy Waters' tour of England with Otis Spann in 1958 marked a significant moment in blues history. Backed by local Dixieland-style jazz musicians, including members of Chris Barber's band, Waters introduced electric slide guitar playing to English audiences who were accustomed to acoustic folk blues. His performances, featuring his amplified sound, initially unsettled traditionalists, earning headlines like "Screaming Guitar and Howling Piano." However, younger musicians like Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies, inspired by Waters' modern electric blues, went on to influence bands like the Rolling Stones, Cream, and Fleetwood Mac.

Throughout the 1960s, Muddy Waters continued to shape the blues scene, particularly through his live performances. His recording of "Got My Mojo Working" at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960 garnered Grammy nomination and showcased his enduring influence. In 1963, he released "Folk Singer," a departure from his electric guitar sound, featuring acoustic arrangements and the then-unknown Buddy Guy. Though not a commercial success initially, "Folk Singer" received critical acclaim and later recognition as one of the greatest albums of all time by Rolling Stone.

Participation in the American Folk Blues Festival in Europe further expanded Waters' reach, showcasing both his electric and acoustic-oriented performances to new audiences. In 1967, Chess Records attempted to cater to a rock audience by releasing albums like "Super Blues" and "The Super Super Blues Band," which featured Waters alongside Bo Diddley and Little Walter. The effort was met with mixed reviews.

In 1968, "Electric Mud" sought to reinvent Waters' sound with psychedelic soul backing from Rotary Connection. Although controversial, the album reached modest commercial success before being criticized by Waters himself for its departure from his traditional style. However, "After the Rain," released shortly after, continued in a similar vein and featured many of the same musicians.

In 1969, Waters released "Fathers and Sons," a return to his classic Chicago blues roots. Backed by an all-star lineup including Michael Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield, the album became one of the most successful of his career, reaching number 70 on the Billboard 200 chart.

Notes

- Palmer, Robert (May 1, 1983). "Muddy Waters, Blues Performer, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- ^ Gordon 2002, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Muddy Waters: Can't Be Satisfied (DVD). Winstar Communications. 2003.

- ^ Cogan, Jim (2003). Temples of Sound: Inside the Great Recording Studios. Chronicle Books. p. 10. ISBN 9780811833943. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ "His thick heavy voice, the dark colouration of his tone, and his firm, almost solid, personality were all clearly derived from House," wrote the music historian Peter Guralnick in Feel Like Going Home, "but the embellishments, which he added, the imaginative slide technique and more agile rhythms, were closer to Johnson.

- a b Palmer, Robert (October 5, 1978). "Muddy Waters: The Delta Son Never Sets". Rolling Stone. p. 55.

- a b Gordon, Robert (May 24, 2006). "Muddy Waters: Can't Be Satisfied". PBS. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ Gordon 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Image at Rolling Stone

- ^ Chilton, Martin. "Muddy Waters: Celebrating a Great Blues Musician". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 25, 2017.