The Natural Maya Method of Water Purification

The ancient Maya people maintained naturally clean water and lived in greater harmony with their surroundings. From them, we can get knowledge.

In Guatemala, a jacana, sometimes known as a lily trotter, makes its way through fields of white lilies. Photo credit: Getty Images/iLantis

Water is life. We must thus take care of it. If there is unfit water to drink, then even an abundance of it is useless. Maintaining sufficient water supplies and water quality for human use is becoming more and more urgent due to factors including pollution, climate change, and population growth. I've studied archaeology in Belize for 35 years, specializing in the ancestors of the Maya, and throughout that time I've learnt a lot about managing water wisely. I now know that they maintained pure water by natural means and lived in greater harmony with their surroundings. From them, we can get knowledge. Because of their inclusive worldview, the Maya connected with the environment differently for millennia before the Spanish invaders arrived in Central America in the early 1500s. Because they believed that everything and everything, including soils, clouds, animals, reptiles, birds, insects, and so on, contributed to the upkeep of the earth, they did not waste resources. Everybody and everything, including Maya, had souls and polite relationships that allowed everything to be alive and connected. They had an orientation devoid of Cartesian dichotomies such as sacred/secular or nature/culture, unlike in modern thought. Nonhumans and humans coexisted and did not put too much strain on one another. Through renewal ceremonies, the Maya celebrated these links and emphasized cooperation in the forest above management.

They approached water in the same manner, seeking approval from the gods of the Earth and Chahk, the god of rain, to harness their resources—soils, limestone, and rain—to construct self-cleaning reservoirs. This specific relationship may hold the key to the most significant lesson they can impart to us in the present.

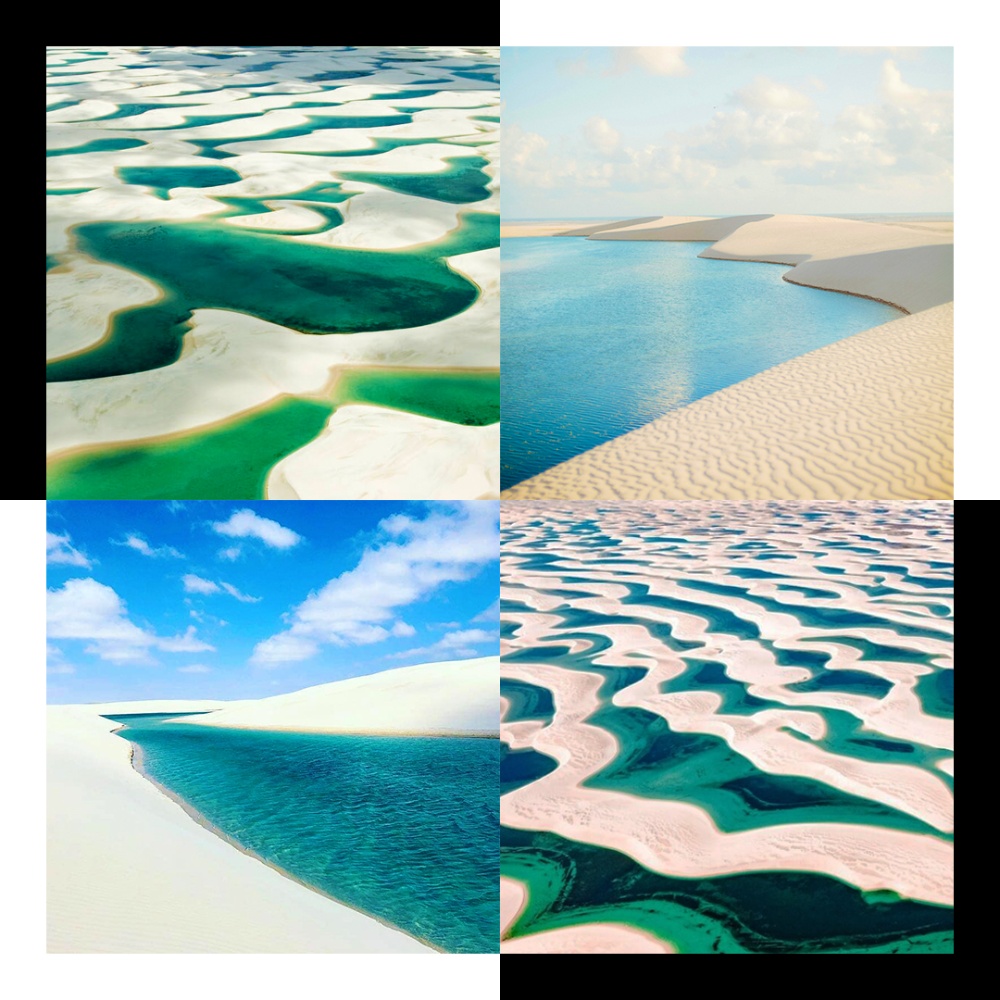

During the Classic period (c. 200–900 C.E.), millions of Maya lived in their southern lowlands region, which included parts of modern-day Guatemala, Mexico, and Belize. During the annual five-month dry season, when temperatures rose and humidity increased, self-cleaning reservoirs, or constructed wetlands (CWs), as they are now called, provided for them. There, during the seven-month rainy season, a large amount of precipitation fell on porous limestone bedrock, leaving little surface water.

That is the reason why millions of people were sustained for over a millennium by reservoirs and monarchs in hundreds of Maya towns. The Maya started building increasingly complex water systems by at least 400 BCE. These persisted until 900 CE when the Maya abandoned the towns due to the effects of multiple protracted droughts that occurred between 800 and 900 CE. More than a millennium of sustainable living was destroyed by climate change, resulting in declining water levels, failed crops, and the fall of monarchs. On the other hand, Maya farmers persisted and still do.

However, how did the Maya people manage to keep their water pure for almost a millennium? by using their understanding of the tropical climate to create reservoirs that can clean themselves? Their waters did not become stagnant or serve as a haven for mosquitoes carrying diseases that spread through the water. The amount of nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen did not accumulate to support the kind of algae blooms that currently cover our beaches. According to the EPA, engineered wetlands are made "using natural processes involving wetland vegetation, soils, and their associated microbial assemblages to improve water quality.” The Maya produced these wetlands. Unlike modern water treatment plants, no chemicals were required.

The aquatic biota in a manmade wetland collaborates to keep the water clean. Nutrients are absorbed by aquatic plants such as reeds, cattails, and water hyacinths, whereas nutrients are broken down by biofilms formed by decaying plants. But that's not all. Like zooplankton or other tiny aquatic microorganisms, some bacteria in water can absorb nitrogen and consume toxic species like parasites. In addition to the many aquatic plants that people used for food, medicine, and tools—such as bamboo for fish spears and reed for basketry—the wetlands of the Maya region still support a variety of different animals, including turtles, crustaceans, eels, mollusks, snails, and fish.

When water lilies (Nymphaea ampla) were present, the ancient Maya understood the water was pure. Why? because these watery plants are delicate. They are limited to growing in still waters that are between three and ten feet deep. The water can't include excessive amounts of calcium, other minerals, algae, or acidity. Put another way, these blossoms are unique to pure water (and the imagery that represents Maya kingship, but that's another tale).

These artificial water habitats are incredible and essential for meeting future water demands. At the moment, civil engineers—like those at the University of California, Berkeley's Sedlak Research Group—are investigating more extensive applications of CWs. They require a lot of work at first, but with little upkeep, they become self-sufficient. When water lilies (Nymphaea ampla) were present, the ancient Maya understood that water was pure. Why? because these watery plants are delicate. They are limited to growing in still waters that are between three and ten feet deep. The water can't include excessive amounts of calcium, other minerals, algae, or acidity. Put another way, these blossoms are unique to pure water (and the imagery that represents Maya kingship, but that's another tale).

These artificial water habitats are incredible and essential for meeting future water demands. At the moment, civil engineers—like those at the University of California, Berkeley's Sedlak Research Group—are investigating more extensive applications of CWs. They require a lot of work at first, but with little upkeep, they become self-sufficient. And they do not need chemicals or fossil fuels to run.

The greenhouse gas emissions from employing CWs are one potential problem. But this can be lessened by gathering aquatic plants, which can then be turned into fertilizer, just like the bottom trash that has been dredged up. We are aware that the Maya would have needed to dredge reservoir bottoms every few years due to the presence of rotting fish poop and other organic materials. Furthermore, they would have needed to replace and restock aquatic plants. The Maya employed extracted aquatic plants and bottom trash for urban fields and gardens because they are rich in nutrients and make excellent fertilizer. Gray water was also released downslope for gardens, urban fields, and orchards, and utilized for fishponds and building projects. Finally, reservoirs attracted game like deer, tapirs and peccaries, as well as waterfowl including herons, cormorants and ducks. The Maya did not waste water.

Where do we even begin to follow their example? A voluntary conversion of a portion of the more than 10 million swimming pools in the United States into CWs with fish, turtles, mollusks, and edible and medicinal plants (as well as fertilizer) is one suggestion. Swimmers could still use them. Businesses now produce self-cleaning pools without the need for chemicals. Let's take it a step further: involvement from families, communities, towns, cities, governments, countries, and multinational companies is required.

Globally, expanding the use of these types of CWs—a technology that humans perfected over a millennium ago—would also help achieve Sustainable Development Goal 6 of the UN, which calls for ensuring that everyone has access to clean water and promoting community involvement.

The ancestral Maya and today's civil engineers can show us the way.

REFERENCES

https://www.scientificamerican.com/

https://www.google.com/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/