The Last Scientist of the Ancient World: Who is Hypatia of Alexandria?

Philosopher, Astronomer, and Mathematician Hypatia

In the 4th century AD, the city of Alexandria had lost much of its former glory. Its wealth had diminished significantly with Roman rule, and the city was marred by civil and religious conflicts. The majority of the city's library had been burned, and the Museum had fallen into disarray, with its last recorded member being a philosopher and mathematician named Theon. Though he was a noteworthy philosopher and teacher in his own right, having made accurate calculations of both solar and lunar eclipses, his fame largely stemmed from being the father of a young woman who attracted considerable attention. This young woman was renowned for her beauty and intelligence, and her achievements in mathematics and philosophy made her one of the brightest inhabitants of Alexandria—her teachings even influencing some of the greatest Pagan and Christian leaders. Her vibrant life and tragic death marked high and low points in ancient world history. Her name was Hypatia of Alexandria.

Hypatia was born around AD 370, and although the exact date is unknown, it was a time when education for girls was rare, and women were forbidden to step outside their prescribed roles. Theon ensured that his daughter received a first-class education. Hypatia learned the intricacies of mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy from her father and quickly proved to be a talented student. Early Christian historian Socrates Scholasticus noted that she inherited her father's extraordinary nature and, despite receiving mathematical education from him, she also delved into other avenues of learning in a noticeable manner.

Hypatia not only learned from Theon but also assisted him in his work. As part of his duties in the Museum, Theon organized ancient texts and wrote critiques on Euclid's "Elements" and the works of the Greek astronomer Ptolemy (not to be confused with the Egyptian king). Hypatia had assisted her father, and a critique she made on Ptolemy's "Almagest" was presented as follows: "Critique by Theon of Alexandria on Book III of Ptolemy's Almagest. The book has been reviewed by my daughter, the philosopher Hypatia."

Hypatia's Mathematical Studies

In a short time, Hypatia began writing her own critiques, including works on the great geometer Apollonius and Diophantus's "Arithmetica." Her writings on Diophantus are detailed, considering he was known as the father of algebra but wrote in a dense and challenging manner. Without Hypatia's clear and understandable explanations, his original works might not have survived, and the foundation of modern mathematics might have been different. Not content with criticizing the discoveries of others, Hypatia soon embarked on her own research. During this time, she developed a new type of astrolabe, an instrument used by astronomers to calculate the positions of the sun and stars. Additionally, she created a series of instruments for further terrestrial observations, including a hydroscope for observing objects underwater and a hydrometer for measuring the density and specific gravity of liquids.

Hypatia's Fame

Around AD 400, Hypatia succeeded her father as the head of the Neoplatonic philosophy school. Students flocked to her in large numbers, and soon, she found herself teaching the children of some of the most powerful families in the Roman Empire. Despite being a Pagan, she freely accepted Christians and Jews, unlike many other schools of the time. While Hypatia's own writings are not extant, much can be gleaned from letters written by her students and records kept by others throughout her life. Socrates Scholasticus, once again, describes her in his Church History:

"In Alexandria, there was a woman named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher Theon, who surpassed all the philosophers of her time in both literature and science. She embraced the Platonic and Neoplatonic schools and delivered the lectures of those schools to those who came from afar. Many came to her to learn philosophy, and through her influence, they rejected the doctrines of all other sects."

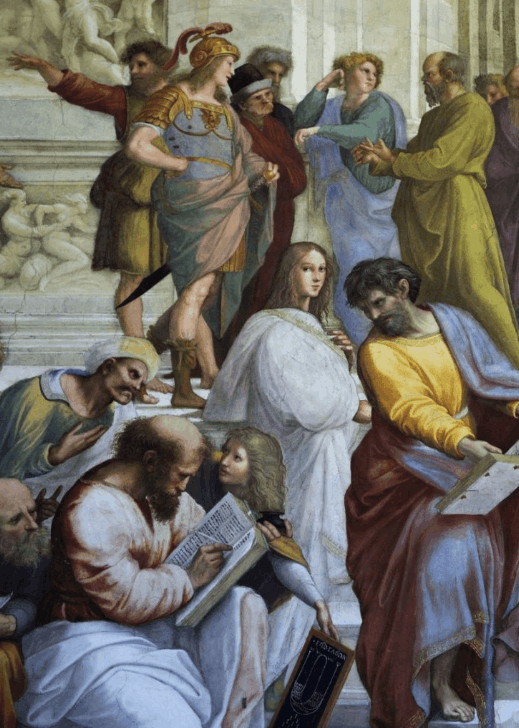

Free Woman Hypatia

In an era when ordinary women in Alexandria rarely appeared outside their homes, Hypatia often conducted public lectures in the city center. Clad in the tightly woven white cloak typically worn by her male colleagues, she spoke eloquently on mathematics, astronomy, history, or the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle. The crowds gathered to hear her were captivated by the breadth of her intellectual knowledge, the passion in her words, and the beauty of her delivery. While no images or sculptures of Hypatia have survived to this day, her physical presence was so well-known that in the 19th century, French poet Charles Leconte de Lisle stated she possessed "the soul of Plato and the body of Aphrodite."

Nevertheless, and perhaps because of this, it is worth noting that a beautiful, articulate, and influential woman does not necessarily conform to the popular image of a mad scientist. Tragically, Hypatia's fate, as told in many famous stories, was not her life but her death. The most talented among mathematicians, astronomers, and inventors met a cruel end in the hands of an angry mob.

Philosopher Hypatia

Alexandria, in the early 5th century, found itself in the midst of a power struggle between Orestes, the civil authority head, and Cyril, the Christian bishop of the city. Hypatia, despite being a Pagan, managed to escape the increasing Christianization of the Roman Empire. As previously mentioned, she accepted students from all faiths, and some of those students went on to become prominent leaders in the church. However, as the conflict between the church and the state escalated, Hypatia found herself caught between two fires. Cyril, realizing the power of a mob, understood that one of the means to rise to a powerful position was the influence of the lower class. When he provided them with something that brought them together, he could direct them towards his own goals. He had already secured leadership in the city's church using the same tactic.

Conflicts Among Pagans, Jews, and Christians

Theophilus, the former bishop of Alexandria, died in AD 412, leaving two candidates to take his place. Cyril, the nephew, had the support of his followers, while Timothy, the head deacon, had the support of the church hierarchy. After three days of bloody street fighting, Cyril emerged as the new bishop. To consolidate his power, he first unleashed his followers on the Christians belonging to the Novatian sect and later on the sizable Jewish population.

Rumors spread wildly, and the violence perpetrated by the followers of the moon was followed by the madness created by the individuals of the moon. The Serapeum, once a temple built by Cleopatra for her lover Mark Antony and converted into a church due to the new religion of the empire, was destroyed, and its library was burned. Cyril incited agent provocateurs to stir up the Jewish community, and Jewish radicals within the community ambushed Christians. Attacks and counterattacks continued for months, and the civil authorities seemed inadequate to stop the events. The streets were painted red with Pagan, Jewish, and Christian blood.

The Brutal Killing of Hypatia

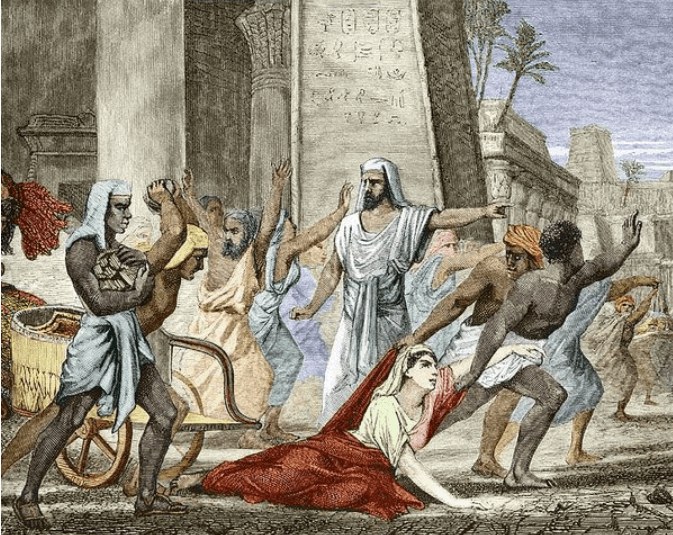

Faced with increasing brutality, Hypatia sided with Orestes. Cyril, long envious of Hypatia for her popularity and influence, retaliated by spreading rumors that she practiced black magic. He accused her of being a "sorceress devoting all her time to magic, astrolabes, and musical instruments." Although the allegations were absurd, they had the desired effect on Cyril's followers. In AD 415, the Christian mob attacked Hypatia. One evening, as she rode in her two-wheeled chariot towards her home, they confronted her. Angry zealots pulled her from the chariot, forcibly removed her philosopher's garments, and dragged her through the streets until they reached a nearby church.

The church, once the Serapeum built by Cleopatra, had been converted into a Christian church due to the empire's new religion. Those who had captured Hypatia took her to the church, threw her onto the floor of the sanctuary, and mercilessly beat her with broken tiles and pottery until she died. When she finally perished, they dismembered her body, carried it outside the city walls, and burned it on a bonfire.

For this woman, who could have been one of the brightest minds of her time, it was a merciless and tragic end. Many historians see her death as the end of the golden age of reason. The Church, to cover up the crime, made futile attempts to destroy all her written works. None of her works have survived to this day, and we only have letters from her students and historical records to bear witness to her brilliance. Perhaps Hypatia's greatest legacy is the wisdom she passed on to her students: "Preserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all."

It is also highly recommended to watch the 2009 film "Agora," which portrays the life of Hypatia.

Thank you for reading.

If you liked my article, please don't hesitate to like and comment.

Additionally, you can check out my other articles:

- The Heart Of Antıque Scıence: The Lıbrary Of Alexandrıa

- Ancient Games

- Viking Mythology

- Music In Plato's World

- Monster Created By Patriarchal Mythology: Medusa

- Forgotten Moon Gods

- Odysseus

- Wordl Mythologies Iconic Couples

- The Most Epic Form Of Love And War: Troy

- King If The Gods: Zeus

- Halloween Mythology And Popular Culture: Witches

- Box, Evil, Woman: Pandora

- Queer Mythology: 7 Legends from Ancient Times

- Cunning, Sneaky, Mischievous, Yet Equally Brilliant: Loki

- The Twelve Great Olympians

- Irish Myths and Legends

- The Epic Of Gilgamesh

- 8 Goddesses You Must Get To Know

- Egyptian Mythology