The Techniques of Chintz

The Techniques of Chintz

Did you know the word chintz refers to a technique, rather than to the fabric itself? As we look ahead to Chintz: Cotton in Bloom, we thought it would be fitting to explore the techniques used to create the textiles that will be displayed during this exhibition.

Origins: From India to Europe

The word chintz comes from the Hindi “chint” or Persian “chitta” meaning “spotted” or “printed”. Originally an Indian hand-painted or hand-printed calico, it became popular in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth century, when it was imported by the Portuguese and latterly the East India Company (VOC).

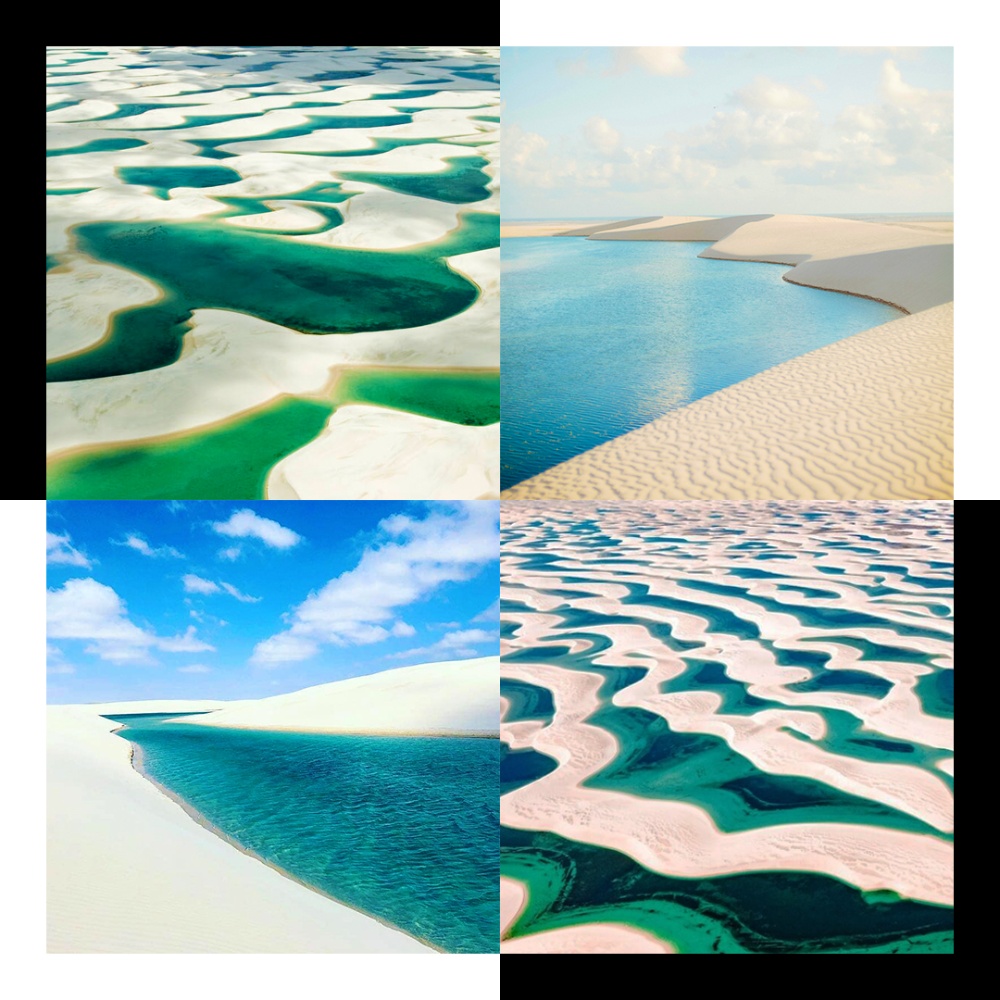

“after many tryalls bought my wife a chintz, that is, a painted Indian calico, for to line her new study, which is very pretty” – Samuel Pepys, Saturday 5 September 1663 Detail of palempore. Cotton, painted and dyed using the chintz technique. India, 1700-1725. Fries Museum Leeuwarden. Photo Studio Noorderblik.

Detail of palempore. Cotton, painted and dyed using the chintz technique. India, 1700-1725. Fries Museum Leeuwarden. Photo Studio Noorderblik.

Decorated with floral motifs and natural forms, this brightly coloured cotton fabric appealed to Europeans in particular. Foremost, cotton was softer than local linen and woollen fabrics, and the shiny vivid finish of chintz looked as expensive as imported silk. Secondly, it showcased hand printing and hand painting techniques largely unknown in Europe at that time. Aided by trade links, chintz soon spread throughout Western Europe.

Chintz was initially an elite fabric, used for wall-hangings, bedspreads and curtains or worn indoors as morning gowns and banyans. However, as cheaper versions were produced, it soon was worn by all classes in society.

Traditional Techniques

“The painting of ‘chints’ proceeds in a most leisurely manner, similar to the crawling of snails which appear to make no headway. Anyone who would represent patience…could use the painters of Palicol as a model.” Daniel Havart, 1693

The traditional techniques used in India to produce chintz were time consuming and complex, as each vegetable dye had to be bound to the fabric using a different chemical. It is worth noting, today the traditional process is a nearly extinct.

Firstly, the calico was flattened and rubbed with buffalo milk and dried myrobolan – a fruit rich in tannin, commonly used in dyeing and tanning. This produced a smooth surface, and the protein in the milk helped the dyes bond to the fabric. This process was repeated several times to treat the calico.

Secondly, a paper pattern was placed on top of the fabric and holes were pierced along the lines in the design. Powdered charcoal was rubbed across the paper, transferring the pattern to the fabric underneath. The outline of the design was then hand painted with a mordant. A mordant is an inorganic oxide such as iron liquor, which when combined with a natural dye, fixes it to the fabric. In this instance, the mordant and dye would produce a black pigment for the outline. At this stage in cheaper chintzes, wooden printing blocks were used to produce the outline of motifs.

Now the dyeing process could begin, the first colour to be dyed was blue. The surface of the fabric was coated with wax, taking care to exclude any areas designed to be blue or green in the finished fabric. After the wax was applied, the fabric was immersed in an indigo vat and then air-dried. As it dried, the indigo would oxidise and produce blue areas. The wax was scraped off and the fabric was washed with boiling water to remove any residual wax residue.

Image: Detail of women’s coat for light mourning. Cotton, painted in chintz technique, India 1750-1800. Fries Museum Leeuwarden – collection Royal Frisian Society.

Image: Detail of jacket. Cotton, painted and dyed using the chintz technique. India, 1725-1750. Fries Museum Leeuwarden. Photo Studio Noorderblik.

Image: Detail of jacket. Cotton, painted and dyed using the chintz technique. India, 1725-1750. Fries Museum Leeuwarden. Photo Studio Noorderblik.

The remaining colours in the design were produced by woodblock printing or hand painting. Firstly, all the areas designed to be white were coated in wax. Again, the natural dyes were mixed with a mordant and applied to the fabric, before being dipped in a dye bath. Indian textiles commonly included red, produced by dipping the fabric in madder bath. Madder plants are found across Eurasia, when the roots are ground-up they can be used to produce red, orange and shades of pink and purple. This stage was repeated several times to intensify the colours.

The fabric was immersed in a solution, such as goat and buffalo manure, to remove any madder from the areas designed to be plain. The fabric was then aged in the sun to remove any residual colour from plain areas and to set the pigments in the areas with pattern.

The final colour applied was yellow, this was produced using pigments found in in saffron, turmeric or curcuma. These pigments could also be applied on to any blue areas to produce green. The final result of these stages was a multicoloured chintz.

Handcrafted to Mass Produced

Due to the lengthy nature of the traditional process, the finished fabric was expensive. As the demand in Europe continued, it is not surprising that soon people began to look for cheaper ways to make chintz. However, Europeans lacked the skills to hand-paint the fabric and used wooden printing blocks instead. By 1750 companies in Switzerland, France and England were leading cotton printing in Europe, producing woodblock printed chintz that approximated, although did not match, the quality of the Indian hand-painted original. Cotton, painted and dyed using the chintz technique. India, 1700-1725. Fries Museum Leeuwarden. Photo Studio Noorderblik.

Cotton, painted and dyed using the chintz technique. India, 1700-1725. Fries Museum Leeuwarden. Photo Studio Noorderblik.

In 1858 the VOC was abolished, and the British took control of the governing of India. By this time England was already producing its own version of the fabric. Chintz remained fashionable into the mid-eighteenth century before falling out of fashion. However, English chintz would reach new heights during the Victorian era when it was mass produced in Britain, coinciding with technological developments and aniline dyes – but this is a topic for another time.

Guest post by Emma Sweeney.

More Information

Chintz: Cotton in Bloom opens 12 March 2021 and will run until 15 August 2021.

Originally curated by The Fries Museum, The Netherlands and on show in the UK for the first time at the Fashion and Textile Museum, Chintz: Cotton in Bloom presents over 150 examples of this highly prized and colourful fabric.

Further Reading

- MacIver, P., The Chintz Book, F.A. Stokes Company, New York, 1929

- Storey, J., Manual of Textile Printing, Thames and Hudson, 1992

- The Diary of Samuel Pepys, <https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1663/09/05/>, Last accessed 15/04/20

- Wilcox, T., Ruth, The Dictionary of Costume, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969

- Yarwood, Doreen, The Encyclopaedia of World Costume, Bonanza Books, 1986