Who is Atatürk?

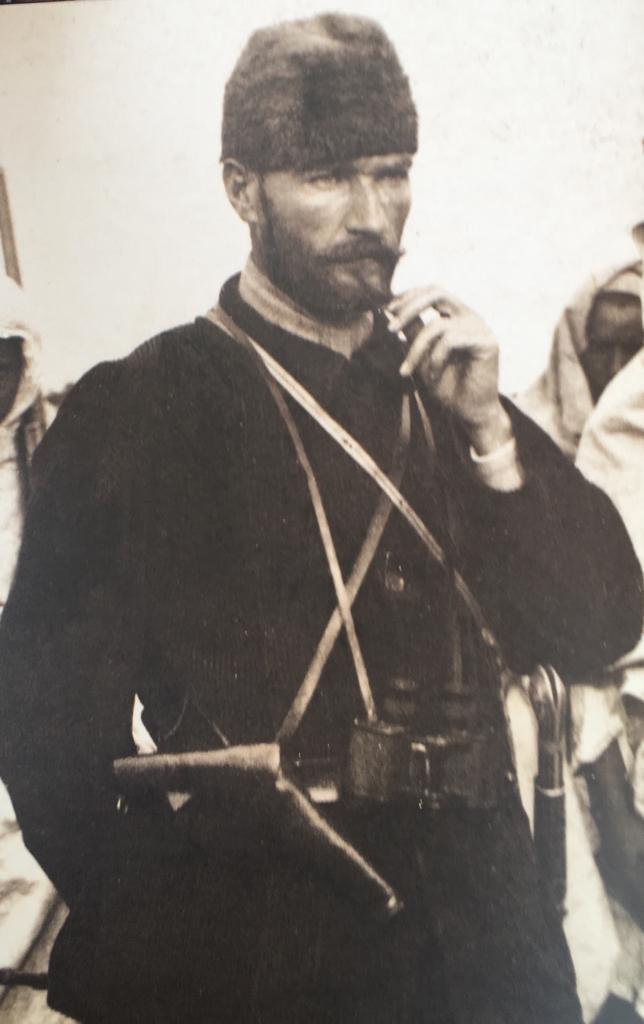

Kemal Atatürk(Turkish: “Kemal, Father of Turks”) (born 1881, Salonika [now Thessaloníki], Greece—died November 10, 1938, Istanbul, Turkey) soldier, statesman, and reformer who was the founder and first president (1923–38) of the Republic of Turkey. He modernized the country’s legal and educational systems and encouraged the adoption of a European way of life, with Turkish written in the Latin alphabet and with citizens adopting European-style names. One of the great figures of the 20th century, Atatürk rescued the surviving Turkish remnant of the defeated Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I. He galvanized his people against invading Greek forces who sought to impose the Allied will upon the war-weary Turks and repulsed aggression by British, French, and Italian troops. Through these struggles, he founded the modern Republic of Turkey, for which he is still revered by the Turks. He succeeded in restoring to his people pride in their Turkishness, coupled with a new sense of accomplishment as their nation was brought into the modern world. Over the next two decades, Atatürk created a modern state that would grow under his successors into a viable democracy. (For a more complete discussion of this period in Turkish history, see Turkey, history of: The emergence of the modern Turkish state.)

One of the great figures of the 20th century, Atatürk rescued the surviving Turkish remnant of the defeated Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I. He galvanized his people against invading Greek forces who sought to impose the Allied will upon the war-weary Turks and repulsed aggression by British, French, and Italian troops. Through these struggles, he founded the modern Republic of Turkey, for which he is still revered by the Turks. He succeeded in restoring to his people pride in their Turkishness, coupled with a new sense of accomplishment as their nation was brought into the modern world. Over the next two decades, Atatürk created a modern state that would grow under his successors into a viable democracy. (For a more complete discussion of this period in Turkish history, see Turkey, history of: The emergence of the modern Turkish state.)

Early life and education

Atatürk was born in 1881 in Salonika, then a thriving port of the Ottoman Empire, and was given the name Mustafa. His father, Ali Riza, had been a lieutenant in a local militia unit during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, indicating that his origins were within the Ottoman ruling class, if only marginally. Mustafa’s mother, Zübeyde Hanım, came from a farming community west of Salonika.

Ali Riza died when Mustafa was seven years old, but he nevertheless had a significant influence on the development of his son’s personality. At Mustafa’s birth, Ali Riza hung his sword over his son’s cradle, dedicating him to military service. Most important, Ali Riza saw to it that his son’s earliest education was carried out in a modern secular school, rather than in the religious school Zübeyde Hanım would have preferred. In this way Ali Riza set his son on the path of modernization. This was something for which Mustafa always felt indebted to his father.

After Ali Riza’s death, Zübeyde Hanım moved to her step-brother’s farm outside Salonika. Concerned that Mustafa might grow up uneducated, she sent him back to Salonika, where he enrolled in a secular school that would have prepared him for a bureaucratic career. Mustafa became enamoured of the uniforms worn by the military cadets in his neighbourhood. He determined to enter upon a military career. Against his mother’s wishes, Mustafa took the examination for entrance to the military secondary school.

At the secondary school, Mustafa received the nickname of Kemal, meaning “The Perfect One,” from his mathematics teacher; he was thereafter known as Mustafa Kemal. In 1895 he progressed to the military school in Monastir (now Bitola, North Macedonia). He made several new friends, including Ali Fethi (Okyar), who would later join him in the creation and development of the Turkish republic.

Having completed his education at Monastir, Mustafa Kemal entered the War College in Istanbul in March 1899. He enjoyed the freedom and sophistication of the city, to which he was introduced by his new friend and classmate Ali Fuat (Cebesoy).

was a good deal of political dissent in the air at the War College, directed against the despotism of Sultan Abdülhamid II. Mustafa Kemal remained aloof from it until his third year, when he became involved in the production of a clandestine newspaper. His activities were uncovered, but he was allowed to complete the course, graduating as a second lieutenant in 1902 and ranking in the top 10 of his class of more than 450 students. He then entered the General Staff College, graduating in 1905 as a captain and ranking fifth out of a class of 57; he was one of the empire’s leading young officers.

Military career

Mustafa Kemal’s career almost ended soon after his graduation when it was discovered that he and several friends were meeting to read about and discuss political abuses within the empire. A government spy infiltrated their group and informed on them. A cloud of suspicion hung over their heads that was not to be lifted for years. The group was broken up and its members assigned to remote areas of the empire. Mustafa Kemal and Ali Faut were sent to the Fifth Army in Damascus, where Mustafa Kemal was angered by the way corrupt officials were treating the local people. Becoming involved again in antigovernment activities, he helped found a short-lived secret group called the Society for Fatherland and Freedom.

Nevertheless, in September 1907 Mustafa Kemal was declared loyal and reassigned to Salonika, which was awash with subversive activity. He joined the dominant antigovernment group, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), which had ties to the nationalist and reformist Young Turk movement.

In July 1908 an insurrection broke out in Macedonia. The sultan was forced to reinstate the constitution of 1876, which limited his powers and reestablished a representative government. The hero of this “Young Turk Revolution” was Enver (Enver Paşa), who later became Mustafa Kemal’s greatest rival; the two men came to dislike each other thoroughly.

In 1909 two elements within the revolutionary movement came to the fore. One group favoured decentralization, with harmony and cooperation between the Muslims and the non-Muslims. The other, headed by the CUP, advocated centralization and Turkish control. An insurrection spearheaded by reactionary troops broke out on the night of April 12–13, 1909. The revolution that had restored the constitution in 1908 was in danger. Military officers and troops from Salonika, among whom Enver played a leading role, marched on Istanbul. They arrived at the capital on April 23, and by the next day they had the situation well in hand. The CUP took control and forced Abdülhamid II to abdicate.

Enver was thus in the ascendancy. Mustafa Kemal felt that the military, having gained its political ends, should refrain from interfering in politics. He urged those officers who wanted political careers to resign their commissions. This served only to increase the hostility of Enver and other CUP leaders toward him. Mustafa Kemal turned his attention from politics to military matters. He translated German infantry training manuals into Turkish. From his staff position he criticized the state of the army’s training. His reputation among serious military officers was growing. This activity also brought him into contact with many of the rising young officers. A feeling of mutual respect developed between Mustafa Kemal and some of these officers, who were later to flock to his support in the creation of the Turkish nation.

The CUP, however, was fed up with him, and he was transferred to field command and then sent to observe French army maneuvers in Picardy. Although consistently denied promotion, Mustafa Kemal did not lose faith in himself. In late 1911 the Italians attacked Libya, then an Ottoman province, and Mustafa Kemal went there immediately to fight. Malaria and trouble with his eyes required him to leave the front for treatment in Vienna.

In October 1912, while Mustafa Kemal was in Vienna, the First Balkan War broke out. He was assigned to the defense of the Gallipoli Peninsula, an area of strategic importance with respect to the Dardanelles. Within two months the Ottoman Empire lost most of its territory in Europe, including Monastir and Salonika, places for which Mustafa Kemal had special affection. Among the refugees who poured into Istanbul were his mother, sister, and stepfather.

The Second Balkan War, of short duration (June–July 1913), saw the Ottomans regain part of their lost territory. Relations were renewed with Bulgaria. Mustafa Kemal’s former schoolmate Ali Fethi was named ambassador, and Mustafa Kemal accompanied him to Sofia as military attaché. There he was promoted to lieutenant colonel.

Mustafa Kemal complained of Enver’s close ties to Germany and predicted German defeat in an international conflict. Once World War I broke out, however, and the Ottoman Empire entered on the side of the Central Powers, he sought a military command. Enver made him cool his heels in Sofia but finally gave him command of the 19th Division, which was being organized in the Gallipoli Peninsula. It was here that the Allies attempted their ill-fated landings, giving Mustafa Kemal the opportunity to throw them back and thwart their attempt to force the Dardanelles (February 1915–January 1916). During the battle, Mustafa Kemal was hit by a piece of shrapnel, which lodged in the watch he carried in his breast pocket and thus failed to cause him serious injury. His success at Gallipoli thrust Mustafa Kemal onto the world scene. He was hailed as the “Saviour of Istanbul” and was promoted to colonel on June 1, 1915.

In 1916 Mustafa Kemal was assigned to the Russian front and promoted to general, acquiring the title of pasha. He was the only Turkish general to win any victories over the Russians on the Eastern Front. Later that year, he took over the command of the Second Army in southeastern Anatolia. There he met Colonel İsmet (İnönü), who would become his closest ally in building the Turkish republic.

The outbreak of the Russian Revolution in March 1917 made Mustafa Kemal available for service in the Ottoman provinces of Syria and Iraq, on which the British were advancing from their base in Egypt. He was appointed to the command of the Seventh Army in Syria, but he was appalled by the sad state of the army. Resigning his post, he returned without permission to Istanbul. He was placed on leave for three months and then assigned to accompany Crown Prince Mehmed Vahideddin on a state visit to Germany.

On his return to Istanbul, Mustafa Kemal fell ill with kidney problems, most probably related to gonorrhea, which it is believed he had contracted earlier. (His physical problems would later require him to have a personal physician in constant attendance throughout his years as president of the Turkish republic.) He went to Vienna for treatment and then to Carlsbad to recuperate. While he was in Carlsbad, Sultan Mehmed V died, and Vahideddin assumed the throne as Mehmed VI. Mustafa Kemal was recalled to Istanbul in June 1918.

Through Enver’s machinations, the sultan assigned Mustafa Kemal to command the collapsing Ottoman forces in Syria. He found the situation there worse than he had imagined and withdrew northward to save the lives of as many of his soldiers as possible.

Fighting was halted by the Armistice of Mudros (October 30, 1918). Shortly afterward, Enver and other leaders of the CUP fled to Germany, leaving the sultan to lead the government. To ensure the continuation of his rule, Mehmed VI was willing to cooperate with the Allies, who assumed control of the government.

The nationalist movement and the war for independence

The Allies did not wait for a peace treaty to begin claiming Ottoman territory. Early in December 1918, Allied troops occupied sections of Istanbul and set up an Allied military administration. On February 8, 1919, the French general Franchet d’Espèrey entered the city in a spectacle compared to the entrance of Mehmed the Conqueror in 1453—but this time signifying that Ottoman sovereignty over the imperial city was over. The Allies made plans to incorporate the provinces of eastern Anatolia into an independent Armenian state. French troops advanced into Cilicia in the southeast. Greece and Italy put forward competing claims for southwestern Anatolia. The Italians occupied Marmaris, Antalya, and Burdur, and on May 15, 1919, Greek troops landed at Izmir and began a drive into the interior of Anatolia, killing Turkish inhabitants and ravaging the countryside. Allied statesmen seemed to be abandoning Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points in favour of the old imperialist views set down in the secret treaties and contained in their own secret ambitions.

Meanwhile, Mustafa Kemal’s armies had been disbanded. He returned to Istanbul on November 13, 1919, just as ships of the Allied fleet sailed up the Bosporus. This scene, as well as the city’s occupation by British, French, and Italian troops, left a lasting impression on Mustafa Kemal. He was determined to oust them. He began meeting with selected friends to formulate a policy to save Turkey. Among these friends were Ali Fuat and Rauf (Orbay), the Ottoman naval hero. Ali Fuat was stationed in Anatolia and knew the situation there intimately. He and Mustafa Kemal developed a plan for an Anatolian national movement centred on Ankara.

In various parts of Anatolia, Turks had already taken matters into their own hands, calling themselves associations for the defense of rights and organizing paramilitary units. They began to come into armed conflict with local non-Muslims, and it appeared that they might soon do so against the occupying forces as well.

Fearing anarchy, the Allies urged the sultan to restore order in Anatolia. The grand vizier recommended Mustafa Kemal as a loyal officer who could be sent to Anatolia as inspector general of the Third Army. Mustafa Kemal contrived to get his orders written in such a way as to give him extraordinarily extensive powers. These included the authority to issue orders throughout Anatolia and to command obedience from provincial governors.

Modern Turkish history may be said to begin on the morning of May 19, 1919, with Mustafa Kemal’s landing at Samsun, on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia. So psychologically meaningful was this date for Mustafa Kemal that, when in later life he was asked to provide his date of birth for an encyclopaedia article, he gave it as May 19, 1919. Abandoning his official reason for being in Anatolia—to restore order—he headed inland for Amasya. There he told a cheering crowd that the sultan was the prisoner of the Allies and that he had come to prevent the nation from slipping through the fingers of its people. This became his message to the Turks of Anatolia.

The Allies pressured the sultan to recall Mustafa Kemal, who ignored all communications from Istanbul. The sultan dismissed him and telegraphed all provincial governors, instructing them to ignore Mustafa Kemal’s orders. Imperial orders for his arrest were circulated. Mustafa Kemal avoided dismissal from the army by officially resigning late on the evening of July 7. As a civilian, he pressed on with his retinue from Sivas to Erzurum, where General Kâzim Karabekir, commander of the XV Army Corps of 18,000 men, was headquartered. At this critical moment, when Mustafa Kemal had no military support or official status, Kâzim threw in his lot with Mustafa Kemal, placing his troops at Mustafa Kemal’s disposal. This was a crucial turning point in the struggle for independence.

Mustafa Kemal avoided dismissal from the army by officially resigning late on the evening of July 7. As a civilian, he pressed on with his retinue from Sivas to Erzurum, where General Kâzim Karabekir, commander of the XV Army Corps of 18,000 men, was headquartered. At this critical moment, when Mustafa Kemal had no military support or official status, Kâzim threw in his lot with Mustafa Kemal, placing his troops at Mustafa Kemal’s disposal. This was a crucial turning point in the struggle for independence.

Kâzim had called for a congress of all defense-of-rights associations to be held in Erzurum on July 23, 1919. Mustafa Kemal was elected head of the Erzurum Congress and thereby gained an official status. The congress drafted a document covering the six eastern provinces of the empire. Later known as the National Pact, it affirmed the inviolability of the Ottoman “frontiers”—that is, all the Ottoman lands inhabited by Turks when the Armistice of Mudros was signed. It also created a provisional government, revoked the special status arrangements for the minorities of the Ottoman Empire (the capitulations), and set up a steering committee, which then elected Mustafa Kemal as head.

Mustafa Kemal sought to extend the National Pact to the entire Ottoman-Muslim population of the empire. To that end, he called a national congress that met in Sivas and ratified the pact. He exposed attempts by the sultan’s government to arrest him and to disrupt the Sivas Congress. The grand vizier in Istanbul was driven from office. The new government, which was sympathetic to the nationalist movement, restored Mustafa Kemal’s military rank and decorations.

Unconvinced of the sultan’s ability to rid the country of the Allied occupation, Mustafa Kemal established the seat of his provisional government in Ankara, 300 miles (480 km) from Istanbul. There he would be safer from both the sultan and the Allies. This proved a wise decision. On March 16, 1920, in Istanbul, the Allies arrested leading nationalist sympathizers, including Rauf, and sent them to Malta.

The conciliatory Istanbul government fell and was replaced by reactionaries who dissolved the parliament and pressured the religious dignitaries into declaring Mustafa Kemal and his associates infidels worthy of being shot on sight. The die was cast—it would be the sultan’s government or Mustafa Kemal’s.

Many prominent Turks escaped from Istanbul to Ankara, including İsmet and, after him, Fevzi (Çakmak), the sultan’s war minister. Fevzi became Mustafa Kemal’s chief of the general staff. New elections were held, and a parliament, called the Grand National Assembly (GNA), met in Ankara on April 23, 1920. The assembly elected Mustafa Kemal as its president.

In June 1920 the Allies handed the sultan the Treaty of Sèvres, which he signed on August 10, 1920. By the provisions of this treaty, the Ottoman state was greatly reduced in size, with Greece one of the major beneficiaries. Armenia was declared independent. Mustafa Kemal repudiated the treaty. Having received military aid from the Soviet Union, he set out to drive the Greeks from Anatolia and Thrace and to subdue the new Armenian state.

As the war against the Greeks started to go well for Mustafa Kemal’s forces, France and Italy negotiated with the nationalist government in Ankara. They withdrew their troops from Anatolia. This left the Armenians in southeastern Anatolia without the protection of the French troops. With the French and Italians out of the picture, Kâzim then moved against the Armenian state. He was assisted by the Bolsheviks, who had established relations with the government of the GNA. Deserting their Armenian protégés, the Russians supplied the nationalists with weapons and ammunition and joined the assault on the Armenian Socialist Republic, which had been their own creation. This combined attack was too much for the Armenians, who were crushed in October and November 1920; they surrendered early in November. By the Treaty of Alexandropol (December 3, 1920) and the Treaty of Moscow (March 16, 1921), the nationalists regained the eastern provinces, as well as the cities of Kars and Ardahan, and the Soviet Union became the first nation to recognize the nationalist government in Ankara. Turkey’s eastern borders were fixed at the Arpa and Aras rivers.

The Greeks were more difficult to overcome, as they continued the advance toward Ankara which had begun in June 1920. By the end of July they had taken Bursa and were pushing on toward Ankara. Ali Fuat was relieved as commander on this front and replaced by İsmet. The Turkish army stood its ground at the İnönü River, north of Kütahya. They threw the Greeks back on January 10, 1921, at the First Battle of the İnönü.

The Greeks did not resume their offensive until March 1921. İsmet again met them at the İnönü River, in a battle that raged from March 27 to April 1. On the evening of April 6–7, 1921, the Greeks broke off the engagement and retreated. In 1934, when the Turks were required by law to take last names, İsmet assumed the surname İnönü in memory of these important victories.

Undaunted, the Greeks launched another offensive on July 13, 1921. İsmet fell back to the Sakarya River, so close to Ankara that the artillery fire could be heard there. Opposition to Mustafa Kemal developed in the GNA, led by Kâzim, who had grown jealous. The opposition demanded that Mustafa Kemal’s powers be curtailed so that a new policy could be developed. In addition they sought to have Mustafa Kemal assume personal direction of the war against the Greeks, anticipating a Greek victory that would result in the destruction of Mustafa Kemal’s stature and charisma. On August 4, Mustafa Kemal agreed, on the condition, which was accepted, that he be granted all the powers assigned to the GNA. He then assumed the role of commander in chief with total authority. He defeated the Greeks at the Battle of the Sakarya (August 23–September 13, 1921) and initiated an offensive (August 26–September 9, 1922) that pushed the Greeks to the sea at Izmir.

With Anatolia rid of most of the Allies, the GNA, at the behest of Mustafa Kemal, voted on November 1, 1922, to abolish the sultanate. This was soon followed by the flight into exile of Sultan Mehmed VI on November 17. The Allies then invited the Ankara government to discussions that resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne on July 24, 1923. This treaty fixed the European border of Turkey at the Maritsa River in eastern Thrace.

The nationalists occupied Istanbul on October 2. Ankara was named the capital, and on October 29 the Turkish republic was proclaimed. Turkey was now in complete control of its territory and sovereignty.

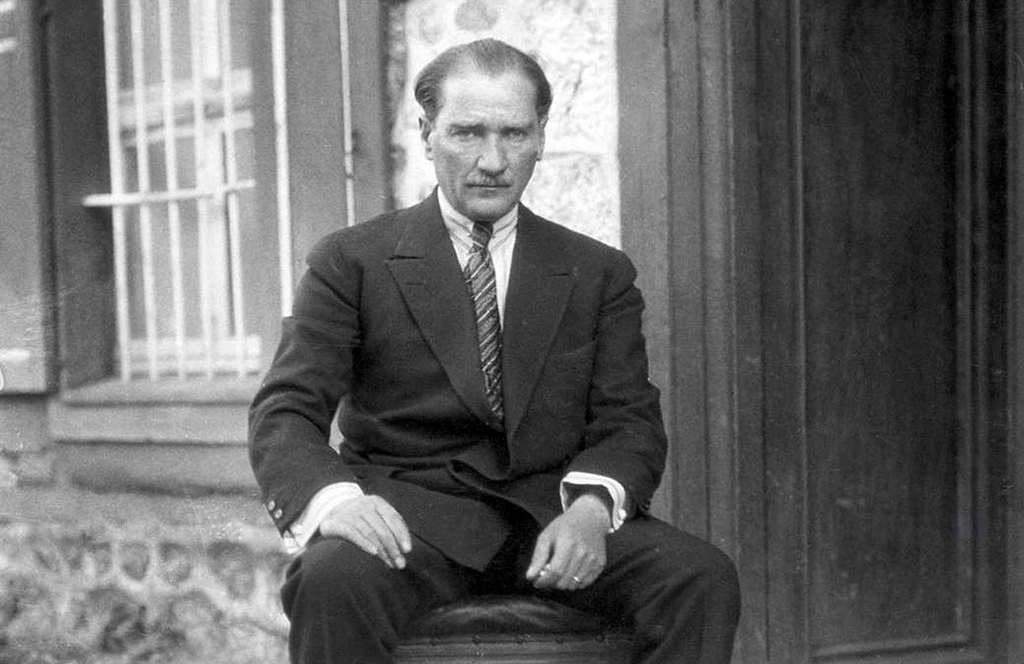

The Turkish republic of Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal then embarked upon the reform of his country, his goal being to bring it into the 20th century. His instrument was the Republican People’s Party, formed on August 9, 1923, to replace the defense-of-rights associations. His program was embodied in the party’s “Six Arrows”: republicanism, nationalism, populism, statism (state-owned and state-operated industrialization aimed at making Turkey self-sufficient as a 20th-century industrialized state), secularism, and revolution. The guiding principle was the existence of a permanent state of revolution, meaning continuing change in the state and society.

The caliphate was abolished on March 3, 1924 (since the early 16th century, the Ottoman sultans had laid claim to the title of caliph of the Muslims); the religious schools were dismantled at the same time. Abolition of the religious courts followed on April 8. In 1925, wearing the fez was prohibited—thereafter Turks wore Western-style headdress. Mustafa Kemal went on a speaking tour of Anatolia during which he wore a European-style hat, setting an example for the Turkish people. In Istanbul and elsewhere there was a run on materials for making hats. In the same year, the religious brotherhoods, strongholds of conservatism, were outlawed.

The emancipation of women was encouraged by Mustafa Kemal’s marriage in 1923 to a Western-educated woman, Latife Hanım (they were divorced in 1925), and was set in motion by a number of laws. In December 1934, women were given the vote for parliamentary members and were made eligible to hold parliamentary seats.

Almost overnight the whole system of Islamic law was discarded. From February to June 1926 the Swiss civil code, the Italian penal code, and the German commercial code were adopted wholesale. As a result, women’s emancipation was strengthened by the abolition of polygamy, marriage was made a civil contract, and divorce was recognized as a civil action.

A reform of truly revolutionary proportions was the replacement of the Arabic script—in which the Ottoman Turkish language had been written for centuries—by the Latin alphabet. This took place officially in November 1928, setting Turkey on the path to achieving one of the highest literacy rates in the Middle East. Once again Mustafa Kemal went into the countryside, and with chalk and a blackboard he demonstrated the new alphabet to the Turkish people and explained how the letters should be pronounced. Education benefited from this reform, as the youth of Turkey, cut off from the past with its emphasis on religion, were encouraged to take advantage of new educational opportunities that gave access to the Western scientific and humanistic traditions.

Another important step was the adoption of surnames or family names, which was decreed by the GNA in 1934. The assembly gave Mustafa Kemal the name Atatürk (“Father of the Turks”).

After having settled Turkey firmly within its national borders and set it on the path of modernization, Atatürk sought to develop his country’s foreign policy in similar fashion. First and foremost, he decided that Turkey would not pursue any irredentist claims except for the eventual incorporation of the Alexandretta region, which he felt was included within the boundaries set by the National Pact. He settled matters with Great Britain in a treaty signed on June 5, 1926. It called for Turkey to renounce its claims to Mosul in return for a 10 percent interest in the oil produced there. Atatürk also sought reconciliation with Greece; this was achieved through a treaty of friendship signed on December 30, 1930. Minority populations were exchanged on both sides, borders were set, and military problems such as naval equality in the eastern Mediterranean were ironed out.

This ambitious program of forced modernization was not accomplished without strain and bloodshed. In February 1925 the Kurds of southwestern Anatolia raised the banner of revolt in the name of Islam. It took two months to put the revolt down; its leader Şeyh Said was then hanged. In June 1926 a plot by several disgruntled politicians to assassinate Atatürk was discovered, and the 13 ringleaders were tried and hanged.

There were other trials and executions, but under Atatürk the country was steadfastly steered toward becoming a modern state with a minimum of repression. There was a high degree of consensus among the ruling elite about the goals of the society. As many of those goals were achieved, however, many Turks wished to see a more democratic regime. Atatürk even experimented in 1930 with the creation of an opposition party led by his longtime associate Ali Fethi, but its immediate and overwhelming success caused Atatürk to squash it.

In his later years Atatürk grew more remote from the Turkish people. He had the Dolmabahçe Palace in Istanbul, formerly a main residence of the sultans, refurbished and spent more time there. Always a heavy drinker who ate little, he began to decline in health. His illness, cirrhosis of the liver, was not diagnosed until too late. He bore the pain of the last few months of his life with great character and dignity, and on November 10, 1938, he died at 9:05 AM in Dolmabahçe. His state funeral was an occasion for enormous outpourings of grief from the Turkish people. His body was transported through Istanbul and from there to Ankara, where it awaited a suitable final resting place. This was constructed years later: a mausoleum in Ankara contains Atatürk’s sarcophagus and a museum devoted to his memory.

Atatürk is omnipresent in Turkey. His portrait is in every home and place of business and on the postage and bank notes. His words are chiseled on important buildings. Statues of him abound. Turkish politicians, regardless of party affiliation, claim to be the inheritors of Atatürk’s mantle, but none has matched his breadth of vision, dedication, and selflessness.