Golden Voyage into Cinema History: The Development of Cinema and the Onset of Conflicts II

While the birth of Documentary Cinema is often perceived as the footage captured by the Lumière Brothers by some groups, another perspective defends the inception of Documentary Cinema with Robert Flaherty's 1922 film "Nanook of the North." Documentary Cinema should uphold reality through evidence and present it to the audience in the best possible manner. The footage obtained by the Lumière Brothers could be considered a form of documentary due to their lack of intervention; however, it cannot be entirely considered documentary due to the absence of a predefined narrative. Flaherty, on the other hand, aimed to portray the lifestyle of an Eskimo family in the Arctic within a more meaningful context, attempting to convey it to the audience. Flaherty's conceptual coherence and understanding of reality have contributed to what we define as the reality side of cinema.

Is it accurate to consider Flaherty as the founder of documentary and the first reflector of reality? To contemplate this, it's essential to gather sufficient data. In my view: we can regard Flaherty as a director who significantly contributed to the formation of documentaries. However, concerning reality, Flaherty portrayed the apparent reality very well but shattered the questioned and contemplated reality entirely. In "Nanook of the North," Flaherty demanded Nanook to hunt using more primitive methods despite Nanook being inclined towards modern methods, thus misleading the audience about the truth. Another instance was when Flaherty had a window carved into an entirely enclosed igloo, where Nanook and his family supposedly lived, to allow the camera's entry. These examples highlight Flaherty's intervention in reality. As Documentary Cinema seeks reality, Flaherty failed to entirely represent reality as a whole. Can a director genuinely portray reality to the audience? The answer is definitely no. Despite claiming to reflect reality, a director will inevitably inject their perspective, starting from the mere positioning of the camera. Hence, presenting reality entirely is not feasible. Moreover, there's another dimension: what defines reality, and whose reality?

Regarding the representation of reality, filmmakers and cinema movements have developed various methods. Vertov denied the existence of a script and aimed to create a whole through shooting certain visuals, arguing that these visuals weren't bound by a script and represented reality. Godard, on the other hand, made several moves to inform the audience that a film is indeed a film to reach reality. If we're to mention a similar movement, the answer would be 'Dogma95' Trier relinquished control of the camera's position to a computer to entirely reflect reality to the audience. He stated that he didn't intervene in the camera, yet relinquishing control from human decisions to a device still constitutes an intervention. Here, intervention remains present.

Cinema's manifesto for reality was introduced by Vertov. He argued that fiction in films is an opiate. These fictions intoxicate the audience, making it easier to later impose distorted truths on an unconscious audience. Therefore, he advocated for real events to be showcased in cinema. Vertov argued that montage demonstrates the director's creativity and influence on the film. In a sense, Vertov considered montage as a cornerstone of a film. Hence, he advocated accessing reality through montage. Kino-Glaz, a movement that sought to simplify cinema and produced documentary films along this path, stands out prominently among trends that emerged in cinema history with the clear intention of capturing reality. Classical narrative structures were rejected in this manifesto, creating a cinema concept without a script. Vertov advocated for the establishment of a Factory of Facts, labeling it as the production of facts in films. The Factory of Facts could be referred to as the inclusion of realities in film. In 1926, Vertov expressed his thoughts in this way: "To truly filmize the worker-peasant USSR, the spread of facts, incitement with facts, propaganda with facts, fists made from facts, creating actual storms with facts..."

Vertov's perspective has evidently shown us the presence of an ideology in representing reality. Just as Flaherty directed Nanook not to use a gun and hunt using primitive methods, distorting reality, Vertov attempted to reach reality within a specific ideological framework, subjecting reality to a certain viewpoint. I argue that where there's ideology, we cannot speak of reality. Both Flaherty and Vertov captured and simultaneously distanced themselves from reality.

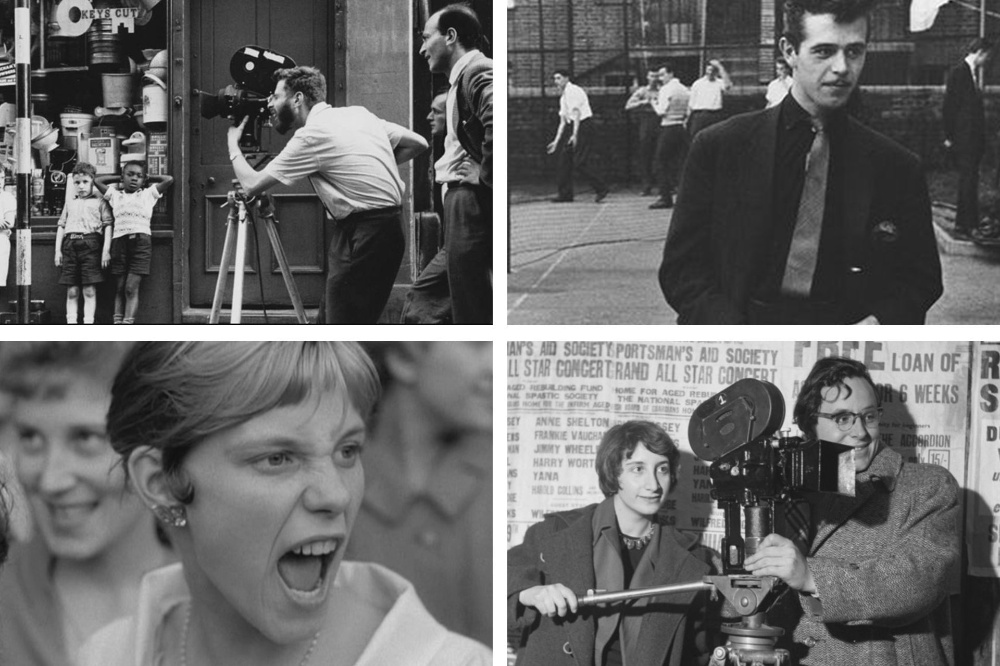

Following Flaherty's reality and Vertov's reality, groups emerged looking at reality from a different perspective. After the transition from analog to digital, lightweight and portable cameras began production. This widened the possibility of mobility for filmmakers, leading them on a quest for pure reality. The first attempts at this emerged in England under the name Free Cinema. Free Cinema was the title of a program that showcased a group of films made by independent directors. Similar to the French New Wave movement, directors began their cinema careers as critics. Anderson laid the conceptual groundwork for the Free Cinema movement with his article "Stand Up Stand Up" on the social responsibility of documentary cinema published in the 'Sight and Sound' magazine in 1956. The most crucial element in the development of Free Cinema was the use of lightweight equipment. Previously bulky cameras, lighting, and sound equipment didn't allow much maneuverability for the documentary filmmaker who belonged on the streets. With advancing technology, the camera descended to the streets and began reflecting real life. Filmmakers roamed the streets, approached people, and reflected their natural states. The focus of the camera was consistently on the same thing: the daily life of the working class. Similar to Vertov's reflection of a specific ideology in his films, Free Cinema solely focused on the working class, attempted to reach reality through a single perspective in documentaries, and endeavored to reflect reality based on a single class. Like other perspectives, the Free Cinema movement also couldn't reflect reality as it truly exists. It was not Free Cinema but another Briton, John Grierson, who first brought the working class to the screen. In the 1930s, British documentary style captured the lives of ordinary people. As Lindsay Anderson explained, the most significant difference among these was Free Cinema's desire to use poetic reality. Where the directors concurred was in having a thought process liberated from mainstream cinema's advertising-oriented approach and carrying influences from Grierson's documentary movement in the 1930s. Finally, we can say that Free Cinema emerged as a presentation program dealing with its independent themes, subsequently expanded as an approach and influenced the British New Wave.

The term of French origin 'Cinema Direct' rapidly transformed into English as 'Direct Cinema'. However, the more commonly used term, 'Cinema Verite,' was first mentioned by French documentarians Jean Rouch and Edgar Norin in the promotion of their film 'Chronicles of A Summer' as a 'cinema real experiment.' The fundamental point where these two similar movements converge is in their origins. Both emerged due to a longing for a new cinematic reality and the discovery of lightweight cinema equipment that facilitated this desire. The term 'Direct Cinema' was coined by Albert Maysles to differentiate it from French Cinema Verite. Unlike Cinema Verite, Direct Cinema aims to be as invisible as possible, to be unobtrusive, as American documentarian Richard Leacock put it (the 'fly on the wall'), leaving events to unfold naturally. In this approach, the subjects are allowed to speak for themselves while the camera merely remains in an unobtrusive recording position. Most directors do not interfere with the unfolding events; events are captured in their unaltered or unrehearsed form. To capture the reality of the subject, hundreds of hours of filming are conducted. This approach aimed to minimize the director's influence on the subject by excluding large production crews, storytelling, intertitles, special lighting, costumes, and makeup. In short, this approach consisted of uncontrolled shootings of real people in real situations. Unlike Direct Cinema, Cinema Verite acknowledges and even makes use of the camera's awareness; thus, it's more self-reflexive. The camera awareness in this movement in France reminds us of France's most important movement, the French New Wave. Particularly, it brings to mind Godard, who pioneered the use of camera awareness, intentionally broke editing and shooting rules, used Brechtian alienation techniques to disrupt the viewer's comfortable position, and constantly reminded the audience that they were watching a film.

The approaches of Cinema Verite and Direct Cinema are among the foremost methods used today to influence the audience and enhance a film's credibility. These movements, which began as a revolution in the pursuit of reality in cinema, have now become a formal preference used not so much in discussions about reality but to enhance the credibility of classical narrative cinema. Fictional cinema also has a perspective on reality. Instead of taking reality as it is, the aim is to show reality as closely as possible to create the impression of reality. This is something that was not present in the aforementioned views on reality. However, I liken this somewhat to what Flaherty did in his film 'Nanook of the North'. Flaherty intentionally distorted reality, yet the audience watched it as if it were real. Fictional cinema aims to approach reality in this way and present the impression to the audience as if it were real. We can easily see this in Classical Narrative films.

Another perspective on reality is Mockumentary. A Mockumentary aims to convince the audience by presenting non-existent things as if they were real, often providing comedic pleasure around this process. Mockumentaries, also known as Faux Documentary, generally inform the audience at the end that these were fabrications. Mockumentaries, which use documentary templates, aim to look completely real. Creating the perception for the audience that what they are watching is real is one of their general objectives. The 'documentary' part of the Mockumentary represents the form, while the 'mock' part represents the fiction. The material of the documentary film is reality, while the primary material of the Mockumentary is fake documents that appear real. It should be emphasized that Mockumentaries challenge not the documentary film itself but the viewer who assumes everything is real without investigating. Regardless of the subject, the underlying text is always the documentary itself, and the Mockumentary invites the audience to remain vigilant. Mockumentaries tend to conceal their fictionality. In general, directors of Mockumentaries demonstrate a reflective stance related to the discourse of reality. Mockumentaries mimic documentary codes and conventions to mock the expectations and assumptions associated with the discourse of reality, cultural situations, and conditions of the documentary. Finally, Mockumentary can be defined as a narrative-based fictional genre that aims to flawlessly imitate documentary codes and conditions to be as close to reality as possible while also making the audience doubt the narrative's trustworthiness regarding reality in cinema.