The Rise of the Product Dictator: Cautionary Tales

If you’re keeping an eye on the tech product zeitgeist, you may have noticed an uptick in CEOs and founders adopting a role which I (unironically) call the product dictator.

A reasonable metaphor for understanding how a product dictator works might be a solar system. The leader is a bright sun around which everyone and everything orbits. But a better one (still in the celestial vein) is a black hole. A product dictator is a person who pulls everything towards them, sucking in decisions, collapsing structures and concentrating power until it creates a distortion field so powerful that nothing can escape.

The product dictator sucks decisions inward until the entire product galaxy revolves around them.

It may be this model is becoming more common (again). For example, Brex recently made an announcement about its new product process, and it sounds a lot like product dictatorship. Founder and co-CEO Pedro Franceschi positioned himself in a recent post as “the ultimate editor,” inexorably pulling the product process towards him in the name of simplicity.

If you read Franceshi’s post and it sounds familiar, it’s probably because Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky has been talking proudly about his own black hole for quite some time now.

And he’s hardly the first. Despite the fact that modern management was supposed to have moved beyond command-and-control decades ago, here we are, right back there.

But why? Why — in spite of strong evidence which shows that leaders who empower and enable with clarity, focus, and trust drive better products and bigger profits — is the product dictatorship again having its moment? The answer to that question is an important cautionary tale.

The Myth of Simplicity

The most popular justification for a product dictatorship seems to be simplicity. Do fewer things better. If everything is a priority then nothing is a priority. Focus. <additional tired management aphorism goes here>

And who could argue? When product dictators justify their model in the name of simplicity, they come off sounding not just right but righteous. There’s a lot to love about simple processes, simple structures, and simple products.

But there’s nothing simple about what a product dictator does. It may seem that way from inside the singularity, looking out through the distorted lens of their own black hole. But the lived experience and real world outcomes are usually very different.

In actual practice, product dictators create an environment of reduced efficiency, decreased velocity, and increased waste.

Reduced efficiency because the product dictator is intentionally single tracking what could otherwise be a multi track process. Decreased velocity because when everyone’s held up on one person’s time and attention, things will slow way, way down. And increased waste, because talented people don’t usually sit on their hands when they’re blocked. They try, they guess, they start, but much of that work comes to nothing when they finally encounter the dictator.

So productivity plummets, talent gets wasted, burnout goes up, and retention goes down. The dictator rarely sees all this from the inside, and may point proudly at the few great features the team ultimately launches. What they can’t point at is the nearly identical work the team tried to build a year ago but couldn’t, or the charred husks of the people they lit on fire along the way.

One thing to note — it’s different in small start ups. At an early stage, with a small team and a sufficiently simple product offering, founders almost have to be dictators. The main challenge is deliberate high-velocity execution and with a very small team and a nascent product, a dictator can pull that off.

But even at a modest level of complexity, it’s just not possible for a single individual to make decisions in a way that’s efficient and high quality. And so what looks simple from the dictator’s POV is actually very much not.

The Rise

So it’s not simple. And it’s not better. But it is increasingly common. As a social psychologist and an executive coach, I think we need to know why if we’re going to untangle it all. Most leaders out there aren’t the extreme version of product dictator we’re discussing here. But talking about the extreme version can still help us see the challenges of any version.

When executives institute a product dictatorship, there are a few things they’re saying without saying:

I am the only one capable of doing this.

I don’t think product work can succeed without me (or I won’t let it).

I don’t believe I can exercise authority or influence in my company unless I’m directly in the conversation.

But those are symptoms, not the disease. There are three underlying factors which drive much of the product dictator’s behavior. Anxiety, ego, and a lack of leadership skills that allow for a balance of directive and empowering leadership makes the product dictator sad.

Anxiety, ego, and a lack of leadership skills that allow for a balance of directive and empowering leadership makes the product dictator sad.

Anxiety. A product dictatorship is often a response to anxiety and fear. There’s no doubt that leaders are under a ton of pressure these days. Public markets and private funders are demanding more growth and less cost. Meanwhile, the macro outlook is unclear amidst a generational upheaval in technology. Product dictators respond by grabbing for the safety blanket of as much control as they can get. Whether it’s creating powerful decision-making bottlenecks or pulling all their employees back to the office where they can physically see them, anxiety and fear is pushing some leaders to do things that fly in the face of the best evidence we have.

Poor Leadership. Never attribute to malice what you can attribute to ignorance or incompetence. Product dictators are often responding to their own lack of leadership capability. They’ve never learned how to effectively do things like set strategy and goals, develop high functioning org structures and product processes. They’re poor communicators. These are the things that allow for strategic focus without the dictatorial bottleneck. But it takes a lot of courage for otherwise successful leaders to admit what they don’t know. So instead of doing that, they double down on leadership behaviors and structures which don’t require it.

Over-Reaction. When you hear the average product dictator’s justification for their new structure, it usually invokes the specter of a previous structure gone awry. It was overly distributed, unfocused, decentralized. The company lost clear direction, became bloated, expensive, pushing so much product without improving the user experience or the bottom line. And of course, all this is very bad. But, thankfully, distributed disaster and product dictatorship aren’t the only two options, which makes it much less compelling as a justification.

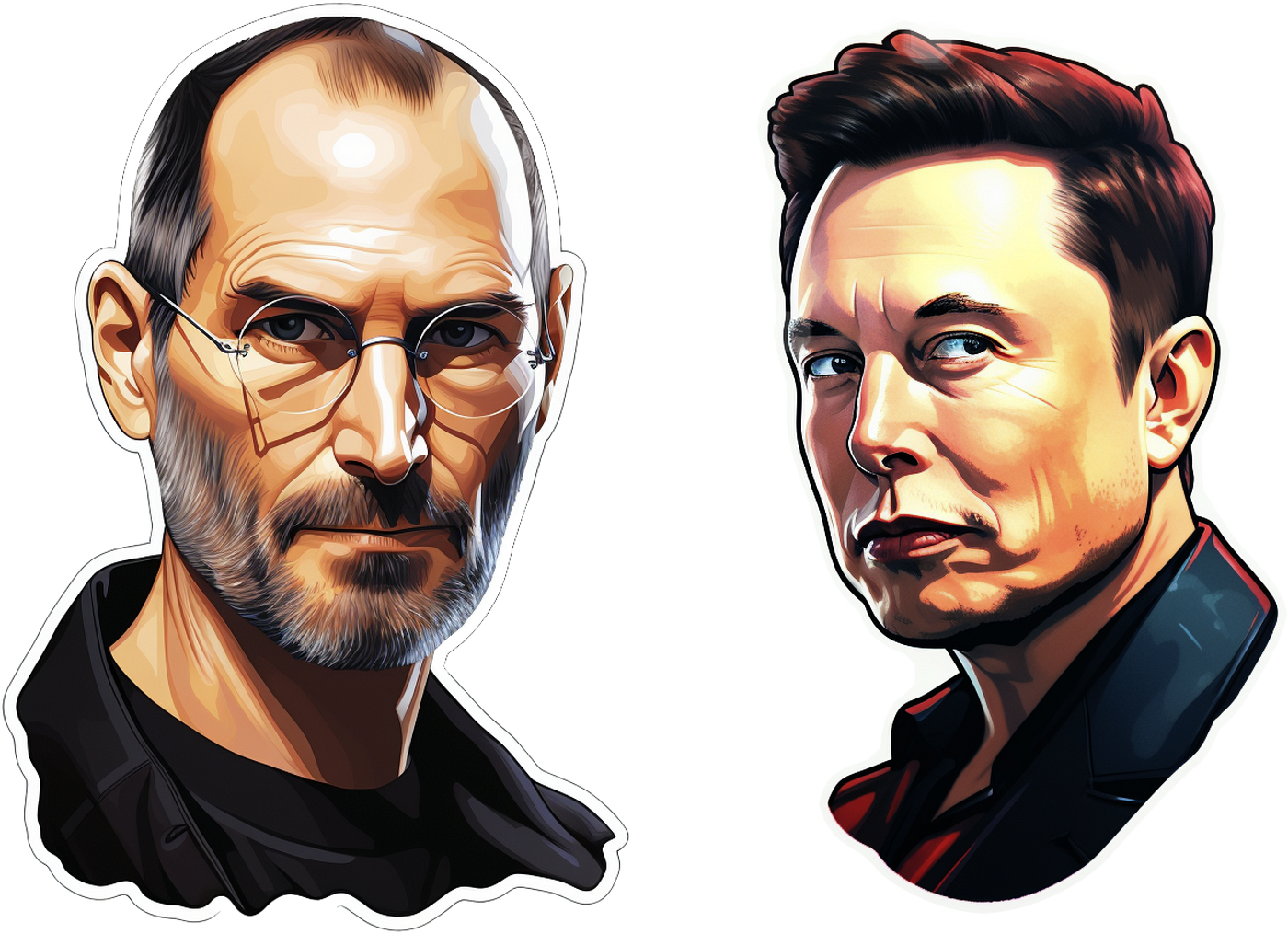

I know I said there were three factors, but I think there’s a quiet fourth one that underlies it all — culture. We collectively glorify the (usually white male) dictatorial genius — Ford, Morgan, Welch, Murdoch, Ellison, Jobs, Musk…

We accept the version of reality those dictators give us, that their gut is an irreplaceable oracle of brilliance. And so we allow for, even encourage them to set up structures that treat their own intuition like the very air we breathe. We train generations of new product leaders to think of themselves as the sun, or the singularity, giving them toxic patterns to follow.

These cultural tropes have become so ingrained that they even show up in the market — case in point, when Tesla’s 2023 investor day highlighted a variety of other talented and knowledgeable leaders at the company. The market took it as a sign that Musk might be stepping back and the stock dropped 6%. There’s plenty to admire in Jobs and Musk, but as leaders they mostly give us examples NOT to follow.

There’s plenty to admire in Jobs and Musk, but as leaders they mostly give us examples NOT to follow.

Conveniently, there’s no counterfactual. We’ll never know for sure what those leaders could have done if they’d not become product dictators. They’ll never know either, which allows dictators to maintain the fantasy that it was all for the better, a success, required, inevitable.

But what if, for example, the incredible progress of talented teams at Tesla and SpaceX is a floor, not a ceiling? I often ask myself about how much more could have been done if Elon Musk had actual leadership capabilities rather than (mostly) a willingness to operate purely on his intuition, a ruthless whip, and a lot of money.

Before Musk, though, there was also Steve Jobs — perhaps the most revered among tech product dictators. But the truth is that in spite of his brilliance, Jobs was a toxic leader. Certainly there is a lot admire in Jobs and even in Musk. But I worry that the recent rise of product dictators means too many have learned the wrong lessons.

The Fall

Sooner or later, the current fad around product dictatorship will be crushed under its own weight. <yes, that was a black hole pun>

In today’s environment (early 2024) it may be easier for product dictators to justify their approach. But the pendulum will swing the other way. It’s simply too obvious that product dictatorships do less with more, waste talent, slow velocity, and limit innovation. Certainly there is good research to support this, but anyone who’s had first-hand experience inside one of these organizations can feel it in their (scorched) bones.

By virtue of market forces, profound realization, or effective coaching, product leaders can learn to do better. And the solution is simple but not easy. Leaders need to ease back from the dictatorship, and set up effective product strategy, planning, and development structures that provide clear, unified direction. They need to provide direction and appropriate oversight to prevent things like misalignment, stagnation, and bloat. And they need to communicate effectively and predictably, while at the same time trusting and supporting leaders around them.

There is no one-size-fits all product model that I know of, but there are many successful paths towards a productive balance of directive and empowering. See, e.g. Marty Cagan’s excellent trio of books — INSPIRED, EMPOWERED, and TRANFORMED.

The main purpose of this article is to try to understand the rise of the product dictator — both the social psychology of the leader and the consequences for their company.

But also, hopefully, to give pause to anyone out there looking at people like Jobs and Musk as models to follow. You, my friend, are no Steve Jobs. And trust me, that’s a good thing.