Navigating Relationship Challenges: Finding Balance and Resilience

Let's say you're out with your partner and your partner is acting quite nervous. So let's say you're joking or you're smiling and your partner is being icy or responding in an angry way.

So you adjust yourself accordingly. Things deteriorate a little bit and it becomes a situation where you say the whole night is ruined.

But when that happens, you don't say the whole relationship is over. Although, if this happens often, you can get to that point.

In this case you can tell him "the whole night is ruined" and that probably means overreacting a little bit. if people behave in a way that is hard to bear, let him behave this way three times while you observe it. The third time when he behaves the same way, say, "Look, this is how you behave". When you say that, he will say, "No, I'm not behaving like that." And you say, "No, you are behaving like that. Look, you behaved like this here and here." In that case, he basically loses and you are a direct winner. But if it's just a one-time thing, it's better not to worry. If it happened once, you have no evidence that it was one time and not a specific problem. But if it happened three times, now you have strong evidence. In this way you strike a balance between being overreactive and standing your ground.

You don't want to be someone who reacts to everything, and you don't want to be someone who can be pushed around. So the three times rule works well for the balance between being too tolerant and being reactive and picking unnecessary fights.

Anyway, you are out with your partner and your partner is being quite annoying and you can't change his behavior. Instead of making jokes, maybe it makes more sense to look at your phone and let him/her calm down on his/her own. This way you don't undermine the framework you use to interact with him/her too much.

After all, the evening is more or less as planned and you can still use the perceptual structures and expectations that guide you.

Imagine this scenario. You're out with your partner and someone walks into the restaurant and comes to your table and says to your partner "hi, I didn't know you had a girlfriend/boyfriend. You didn't tell me about it when we met last week." Now this is a completely different scenario. Yes, you all laughed when you heard this scenario because you know it's really a completely different scenario.

So why the second scenario more shocking than the first scenario? If your assumptions about the world are in a sense organized in a hierarchy, the little little things you do are micro-details at the bottom of that hierarchy. When you get to the top of the hierarchy, abstract by abstract, there is an assumption that "I am in a loyalty-based relationship". Now there are other levels of hierarchy between being in a loyalty-based relationship and micro-details.

The higher up in the hierarchy the shake-up is, the more angry and stressed you get. An annoying partner may not be much of a problem, but a partner who cheats on you is a jolt at the top of the hierarchy. At this level the shaking makes you question your past and your future and maybe even who you really are and who the other person is.

Isn't this a real disaster? A catastrophe that shatters everything. This is the journey into the underworld that we were talking about earlier. Piaget had a similar idea, because Piaget's theory of the stages of development was marked by such ups and downs. As children build themselves upwards from the motor systems, they animate these little sub-elements that are their own and useful. But sometimes these tools, these sub-personalities that they are building, do not fulfill the desired results. For example, a 3-year-old child goes to kindergarten but has difficulty making friends.

This child comes home crying, angry and shaken, saying "nobody wants to play with me". You know that the child then he really cries. It is as if the child has been transported from a field in which he is competent to a field in which he is not competent. Emotions, especially negative emotions, signal that you have moved from a field in which you are competent to a field in which you are not competent.

If you cry, it is usually a sign of anxiety or pain. Sometimes anger makes you cry, but crying usually signals anxiety and pain. It means that you are in a situation where what you know is no longer enough to produce the results you desire. So you cry and you get help. People come and ask what is wrong and support you. Maybe they console you, maybe they give you advice on what you should do.

Or you, if you are an intelligent parent, you play with your child and you help him to develop his skills of social interaction with other people.

Or you take him to places where he can play more with other children, you observe him, you help him to develop these little sub-personalities and you give him more information, you give him more you make him sophisticated.

It is a combination of Piagetian ideas of Stage Theory. It is an upward progression punctuated by falls. It is the confusion caused by the previous structure no longer adapting well to the world, and the subsequent assimilation and adaptation.  Piaget used to think of assimilation and adaptation as opposites, but they are not exactly opposites, and this is a difficult thing to understand. But for Piaget, assimilation means that the human being is the information into the current structure and the structure into which the information is absorbed doesn't change much. Adaptation means that one absorbs a huge volume of information, usually negative information, and then rebuilds that structure by creating a big shake in the structure that you use to understand that information.

Piaget used to think of assimilation and adaptation as opposites, but they are not exactly opposites, and this is a difficult thing to understand. But for Piaget, assimilation means that the human being is the information into the current structure and the structure into which the information is absorbed doesn't change much. Adaptation means that one absorbs a huge volume of information, usually negative information, and then rebuilds that structure by creating a big shake in the structure that you use to understand that information.

Piaget thinks of these as assimilation and adaptation, but it is easier to think of them as a continuum, with assimilation at the microbehavioral level. For example, you try to hold a fork but your hands are numb. You try to grasp the fork a few times but you can't. Then you change your grip and you can hold the fork. I mean, it's just a little bit frustrating, it's just that you look at the fork and you change your grip angle and the world doesn't come crashing down on you because of that. But if you get a dead mouse in your soup, it's much more frustrating, and again it's a hierarchical problem.

So at the lowest level, close to the motor movement structures, assimilation is easy: All you have to do is to make small changes to what I like to think of as a map, a map or a personality. I know the personality and the map seem to be distant things, but in fact they are very similar. Is it a matter of small adjustments or whether you should throw the whole structure in the trash. So the problem is solved by tightening the lug nut or by buying a new car. You can think of your levels as levels of difficulty.

There is another way of thinking about it.

You need to know this because you need to understand how you decide how stressed you are when something goes wrong. This is a very difficult question.

How much should you worry when you wake up one morning with a pimple on your face? We don't know. Maybe it's nothing, maybe six months later you are going to die of cancer. You don't know that. It's not so obvious how people adjust how stressed they get if something goes wrong. Because it's not so obvious how bad things go wrong.

Let's say you go out for dinner and your partner treats you badly. Does that mean you're going to break up in 2 weeks? Actually, maybe that's what it means.

So why don't you freak out that it's the end of the world? You know, some people they can really behave like that. These are people with high levels of negative emotions, that is, people with high emotional instability. These people behave as if they are about to suffer a catastrophe at the slightest abnormality, uncertainty, danger, absenteeism or unexpected situation, whereas an emotionally balanced person, when they are told "I want to leave", they look a bit sad and maybe even that doesn't bother them too much.

So if you drop down this hierarchy of motor movements from the lowest micro-behaviors to gradual abstractions, you can understand how you calculate how much anxiety you're going to feel when something goes wrong. You assume the problem is small and you check it at the lower level. If it is not solved at that level, you move up one level. When your car breaks down, you don't immediately buy a new car. First you check, for example, if the battery is dead. Because this is the way that will give you the least trouble. And it's also a good scheme for clearing the mind.

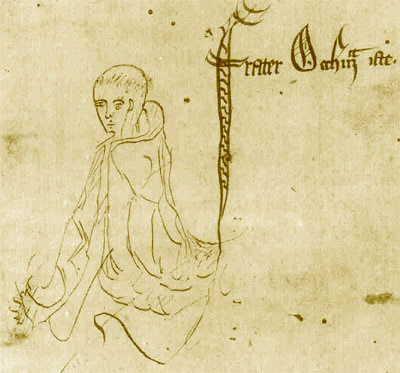

This is similar to the principle of Occam's Razor. You know Occam's Razor, right? You should know this. Occam's Razor is a principle put forward by the medieval thinker Occam. Occam says "don't multiply your explanatory principles more than necessary".  What does that mean? If you have 6 explanations for why something is going wrong, rank them from simple to complex and take the simplest explanation. If that explanation is insufficient, take the next simplest explanation and so on until the explanation is sufficient. Occam's Razor is a guiding principle often used in science. If you have a simple explanation, don't make it more difficult with a bunch of complicated assumptions. This may actually underline a deeper truth: any set of entities is unlikely to be in any configuration, but it is very unlikely to be in the least likely and most complex configuration.

What does that mean? If you have 6 explanations for why something is going wrong, rank them from simple to complex and take the simplest explanation. If that explanation is insufficient, take the next simplest explanation and so on until the explanation is sufficient. Occam's Razor is a guiding principle often used in science. If you have a simple explanation, don't make it more difficult with a bunch of complicated assumptions. This may actually underline a deeper truth: any set of entities is unlikely to be in any configuration, but it is very unlikely to be in the least likely and most complex configuration.

Anyway, I hope that's clear. You can mix all these ideas together. At the bottom of the personality hierarchy are behaviors; at the top are abstractions, like moral abstractions like "be a good person". When something unexpected happens to you, how much anxiety and pain you feel is proportional to the height in the hierarchy of the level that seems to be damaged. proportional. You will have to estimate this level somehow, and this estimation depends partly on your temperament. If you are a highly emotionally unstable person, you will guess that you have suffered a disaster, but if you are a low emotionally unstable person, you will think that it is okay. This prediction depends partly on how you perceive your own competence.

Even if you are an emotionally unstable person, if you are someone who has faced problems in the past, small and big, and solved them and learned from them, you will probably say "yes, this is a problem, but I am a problem solver, so this problem is not a problem", which is a good way of thinking about yourself. That is better than saying "there is no problem". Good luck anyway if you think like that. It is much more useful to say, "I am a person who can solve a problem successfully if I concentrate on the problem."

![[LIVE] Engage2Earn: Veterans Affairs Labor repairs](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/1cbacfad-83d7-45aa-8b66-bde121dd44af/1)