Crowds are terrible predictors. Here’s what you can do about it.Biases and fallacies lead to

Image courtesy of smartandrelentless.com

Image courtesy of smartandrelentless.com

Erdoğan will definitely lose.

On Saturday afternoon, a family member sent me an article about the Turkish presidential election, which was taking place the next day. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the headline said, was about to lose power after twenty years in charge.

I’d heard something similar on the radio a few hours before. Journalists and pundits confidently predicted a loss for Erdoğan, and gave a sequence of obituaries to his two decades in power, as if his exit from government was a foregone conclusion. Media largely predicted a loss for Erdoğan in the presidential election.

Media largely predicted a loss for Erdoğan in the presidential election.

I checked the betting odds for the election. They predicted that Erdoğan would lose with 70% probability, or odds of 3/7. In other words, if Erdoğan won the voting round, you would more than treble your money.

Now, I’m no expert in Turkish politics. The radio pundits, columnists and journalists surely knew much more about the topic than I did.

But I went ahead and bet on a win for Erdoğan. In the rest of this article, I’ll explain why.

By the way, If you’re interested in the financial markets, I recommend joining us at Sharestep — a tool I created that transforms the stock market into a marketplace of ideas.

Opinions are like experts.

I didn’t bet on Erdoğan because I thought he would win, and certainly not because I wanted him to win. I have no special information or expertise in Turkish politics, and my feelings on the president are, at best, neutral.

But I did have one insight that could give me an advantage.

I knew that, as we’ve seen in recent years, mass narratives lead to distorted expectations of important events — and therefore, the odds of an Erdoğan victory were probably attractive.

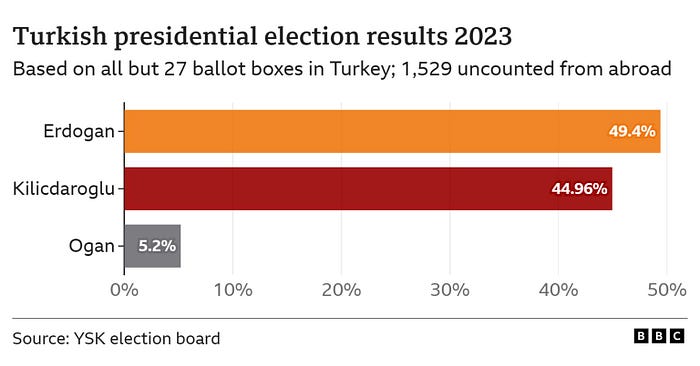

As it turned out, he won the first round ballot by a comfortable margin of two million votes, and is expected to gain a parliamentary majority in Turkey. The odds of him remaining president now sit at around 85%.

Let’s get into the details of what’s going on here — specifically, let’s look at how I used the narratives of crowds to my advantage. Erdoğan won the first round by roughly 2 million votes. Courtesy of bbc.co.uk

Erdoğan won the first round by roughly 2 million votes. Courtesy of bbc.co.uk

Everyone gets it wrong together.

This was not my first encounter with mass prediction errors. I’ve been following political odds for many years. In the past, foolishly, I believed that market odds reflected the most likely outcome. In other words, I believed in the Efficient Markets Hypothesis.

Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH): share prices reflect all information, and consistently beating the market is impossible.

The EMH views markets as collections of independent, rational participants. Market prices are a reflection of many people thinking very carefully, and putting their money where their mind is. A huge ensemble of participants should get as close as we can to an accurate market price. Right? Efficient Markets Hypothesis. Courtesy of open.edu

Efficient Markets Hypothesis. Courtesy of open.edu

I was in Soho in New York on the eve of the Brexit vote in 2016. That evening, the betting markets predicted a resounding vote for the United Kingdom to remain in the European Union, with odds close to 90%.

Neither was there doubt in the press. Even pro-Brexit columnists were convinced that the UK would remain. But later that night, it turned out to be folly, and the United Kingdom voted to exit the EU.

Similarly, in 2015, the betting markets predicted a comfortable victory for Hillary Clinton against Donald Trump in the U.S. presidential election. Then too, as we now know, both public discourse and the markets failed to predict the outcome.

As we’ll see later, increasingly, market unanimity gives us almost no information about eventual outcomes. Market unanimity is an unreliable predictor. Courtesy of corporatefinanceinstitute.com

Market unanimity is an unreliable predictor. Courtesy of corporatefinanceinstitute.com

The financial markets are different.

The astute reader might have some reservations by this point. “Sure, but those are betting markets. Gamblers don’t know what they’re doing. The financial markets are different.”

Surely, in the capital markets, the level of sophistication and rigour is superior to the prediction markets. After all, finance professionals are responsible for tens of trillions of dollars of the world’s wealth.

Let’s test this by seeing how the financial markets performed, again, in the weekend election in Turkey.

Erdoğan has not been a great friend of the capital markets in recent years. His unorthodox approach, some claim, has led to runaway inflation, which sits at around 42% currently, as well as a large debasement of the Lira. Therefore, a fresh face in the Turkish presidential office would be favoured by markets.

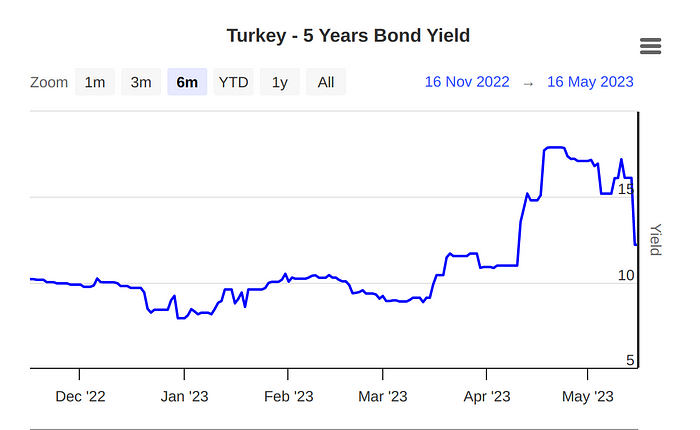

And, as it turns out, markets were also betting on a new regime in Turkey. The 5-year-bond yield showed increased optimism in the months of March through May (when government bond yields rise, it’s often a sign of positive economic sentiment). Bond managers, alas, made the same mistake as everyone else by betting on a loss for Erdoğan. Turkish 5-year bond yield. Since the weekend, yields have fallen.

Turkish 5-year bond yield. Since the weekend, yields have fallen.

Indeed, the last thirty years of history are full of mass failures to predict. To name a few, in 1987, 1998, 2000, 2008, 2011 and 2018, many major capital markets experienced unpredicted downturns. Market downturns have seldom been predicted. Courtesy of tradebrains.in

Market downturns have seldom been predicted. Courtesy of tradebrains.in

The Inefficient Imagination Hypothesis.

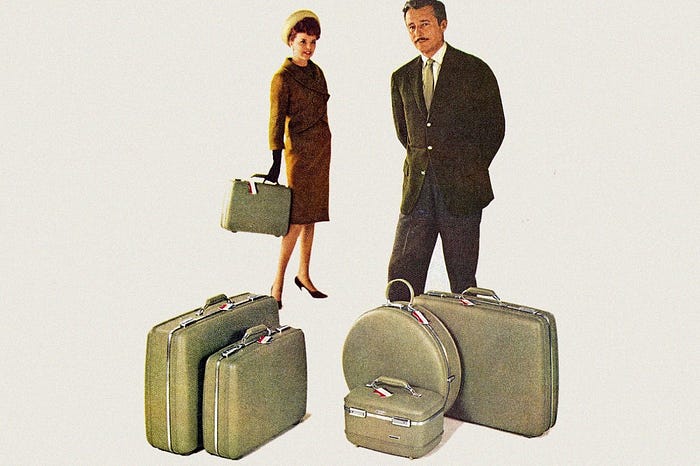

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, in his fantastic book Antifragile, pointed out an interesting anecdote. The common suitcase is an ancient invention, but it started to resemble the modern travel accessory in the 18th century.

However, it took hundreds of years, until 1970, for someone to create a suitcase with wheels on it. This is a remarkable delay in imagination. In the meantime, millions of travellers had to carry their luggage against gravity.

In hindsight, the wheeled suitcase is not the only invention that saw inexplicable historical delays. The electric car was feasible in the early 20th century. The photovoltaic technology in solar panels was invented in the 19th century. So why are the results of these discoveries only manifesting now? Suitcases in the 1960s. Courtesy of ultraswank.net

Suitcases in the 1960s. Courtesy of ultraswank.net

Maybe the marketplace for inventions, just like the betting markets and the financial markets, is inefficient. It is, after all, another marketplace of ideas. It could be that biases, delays and distortions also appear in the inventions marketplace.

In general, we could call what they have in common the Inefficient Imagination Hypothesis, and define it like this:

Inefficient Imagination Hypothesis (IIH): the collective human imagination, being subject to irrational biases and fallacies, is not an efficient price setting system.

So what is going on under the hood? Why, as a collective, are we so bad at arriving at the right idea, at the right time?

Psychological fallacies of individual predictors.

There are a number of reasons why individual predictors rarely hit the mark. For one, the future is inherently random and unpredictable. When we try to make predictions out of the swelling, chaotic systems of human civilisation, the task is often not simpler than trying to predict the weather a week ahead.

What’s more, the so-called narrative fallacy leads us to simplify complexity into concise narratives we can understand, but that often don’t reflect the truth of what underlies them. These simplified narratives then become memetic chains which circulate through the population, causing further distortions (more on that later).

Narrative fallacy: the tendency for people to favour simple narratives when seeking to explain phenomena.

The narrative fallacy. Courtesy of ianhathaway.org

The narrative fallacy. Courtesy of ianhathaway.org

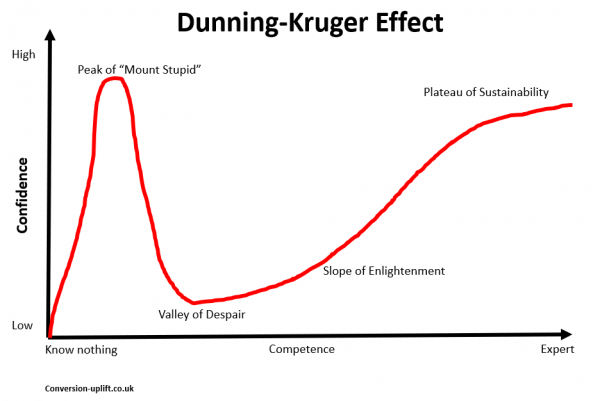

There are other psychological fallacies and biases that impede our ability to forecast accurately. The Dunning-Kruger effect leads us to believe we know more about a given topic than we actually do. In other words, the less we know, the more confidently we predict.

Dunning-Kruger Effect: a lack of knowledge about a particular topic leads people to over-estimate, rather than under-estimate, their understanding of it.

The Dunning-Kruger effect. Courtesy of conversion-uplift.co.uk

The Dunning-Kruger effect. Courtesy of conversion-uplift.co.uk

What’s more, in psychology research, there is something known as the recency bias. The recency bias, discovered by psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, leads us to think that something that happened recently, is likely to happen again. For instance, if someone has burgled your house, you will spend some time over-estimating the probability of another burglary.

Recency bias: when an event occurs, a person is more likely to temporarily over-estimate the probability of it happening again.

The recency bias causes havoc in speculative markets. Recent stock rises predict further stock rises. Recent wars predict further wars. Recent unseated strongmen predict further unseated strongmen. And so on. The recency bias. Courtesy of technology-signals.com

The recency bias. Courtesy of technology-signals.com

The familiarity bias and mass error in crowds.

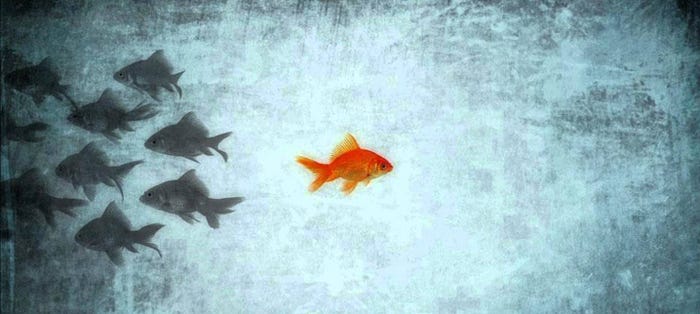

We’ve described some sources of error in individual participants. But what happens at the collective level, with information travelling constantly between market participants, pundits, commentators and influencers?

It turns out that biases, fallacies and distortions make it even harder to predict well, when submitted to the influence of mass information and large crowds.

Enter the familiarity bias, discovered by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Psychology experiments have shown that people are more likely to believe a statement is true, merely because they have heard the statement before, regardless of the objective truth of the statement.

Familiarity bias: a person is more likely to believe a statement is true if they’ve heard it previously.

When you read news headlines, opinion columns and social media commentary, you are subjected to repetitive arguments constantly (just consider the nature of the “re-tweet”). Repetition makes you receptive to narratives, and makes you more likely to think they are true. In the cases when those narratives are inaccurate, more information equals less accuracy.

The familiarity bias is sometimes misinterpreted to mean just a sense of comfort with what you know. Here, we’re pointing out something more nuanced. Just the act of hearing or reading something, increases your sense that it’s true. The more you hear it, the greater the sense.

For example, reading the statement “Paul Bradsheen was good at polo” increases your belief in its truth. I’ll leave it up to you to decide if the statement is true or not. In marketing, repetition is key. Courtesy of businessgrowthguys.com

In marketing, repetition is key. Courtesy of businessgrowthguys.com

At the level of mass participation, we can start to see what happens. Simple, repetitive arguments, aided by the narrative fallacy, attach themselves to people, and are then strengthened by the familiarity bias. Soon, a majority of participants are in agreement about the narrative.

Erdoğan will obviously lose. The Nasdaq is obviously about to crash. Amazon is obviously going to post earnings in line with expectations. Herd stampede. Courtesy of corporatefinanceinstitute.com

Herd stampede. Courtesy of corporatefinanceinstitute.com

Acting efficiently in inefficient markets.

Predicting the future is hard — usually impossible. But betting against crowds is often a good idea. So how can we use this knowledge in speculative markets — financial, political, inventive, or otherwise?

Let’s conclude with a few heuristics worth remembering.

1/ Bet against unanimity.

Because of the familiarity bias, the Dunning-Kruger effect, the narrative fallacy, and other related sources of error, mass markets often overshoot in confidence. In other words, when the market predicts unanimously, the other side of the bet is better priced.

This point is important — even if the market is betting on the most likely outcome, it has probably overshot in confidence. Even if Erdoğan was at risk of losing on Sunday, the 70% probability of him losing was overstated. The odds for a win were still the best bet.

Betting against unanimity almost always has a more attractive price, than betting alongside it. Betting against the market is usually the best bet. Courtesy of mettelray.com

Betting against the market is usually the best bet. Courtesy of mettelray.com

2/ Disconnect from sources of errors.

As we saw, more information equals less accuracy (because of the familiarity bias). In today’s world of repetitive, memetic media, our brains are tricked into believing all kinds of things, whether or not they’re true.

The solution to this is self-evident: disconnect from information sources that are vulnerable to mass error. This isolates you from errors of collective judgement.

Instead, use information sources that are independent in time. Books, for example. Current events, after all, can’t change the contents of a book. This can give a more nuanced view of things, and help you make better predictions, and spot mass errors more easily.

In a nutshell: read fewer newspapers, watch less expert analysis, engage in fewer social media discussions, and read more books. Books are not influenced by changing crowd narratives. Courtesy of influencemagazine.com

Books are not influenced by changing crowd narratives. Courtesy of influencemagazine.com

3/ The I don’t know heuristic.

Socrates was fond of saying that he knew nothing. Indeed, he saw this as the source of his wisdom. Questioning how much you actually know about a subject under discussion can be a useful aid. By asking yourself whether you know enough to have an opinion, you limit your chances of being fooled by the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Recall that when I bet on Erdoğan, it wasn’t because I knew anything special about Turkish politics, or the current election. All I knew is that most participants didn’t know much more than I did, and that, therefore, they had overloaded the other side of the bet.

You could call this the I don’t know heuristic. Or in old fashioned terms, being humble. Socrates was fond of saying that he knew nothing. Courtesy of philosophymt.com

Socrates was fond of saying that he knew nothing. Courtesy of philosophymt.com

In conclusion.

Most of the time, betting with the market is foolish. As I’ve tried to show, it is often a better idea to bet against others’ predictions, especially when the market is unanimous in its consensus. And often, gaining insights from disconnected information sources can put you in a stronger position than plugging yourself into the errors of crowds.

These are some of the reasons I created Sharestep, an AI tool that transforms the stock-market into a marketplace of ideas. It’s a tool that allows investors to find stocks that match exactly what they think is going on in the world. There are no stock pickers, commentators, experts or analysts getting in the way. Sharestep’s users depend on themselves to pick the best ideas and gain an advantage.

For example, with Sharestep, it’s trivially easy to search the stock-market for investments in topics like “lower inflation” or “rare earth metals”. You can search for investments related to just about any topic you can think of.

What’s more, it’s free to try, and if you like the tool, a subscription costs £4.99 (about $6.00) a month, the price of a sandwich.

In any case — thanks for reading, and see you next time.