On central banking and monetary policy

Debt-deflation dynamics

FED’s actions during the GFC

FED’s policy response to the 2007–2008 crisis proved to be effective. (Here we don’t discuss the long-term consequences of FED’s policy which can be debated). If Bernanke was successful in his actions, it was because he was standing on the shoulders of a giant, namely Milton Friedman’s. Friedman’s analysis of the Great Depression of 1929–1933 showed that the central bank had not been accommodative enough to avoid the dramatic fall in the money multiplier. Banks were so frightened that they preferred saving up their reserves instead of lending them. The result is infamously known today: the money supply collapsed, and the US economy fell into deflation.

Since Bernanke’s knowledge drew upon Friedman’s research, he knew what to do under these circumstances. Before the crisis the money multiplier was 8; during the crisis it decreased to 3 which was less than its precrisis value. (By the way, money multiplier of 3 means that a dollar of base money in the banking system supported $3 of money supply in the overall economy).

FED was aware how chaotic and violent the deleveraging process could be. Fortunately, learning from history helped them and the economy — they created an environment where the deleveraging occurred in a relatively benign manner. By being able to offset the collapse in the money multiplier, they saved the US economy from much worse consequences. For example, while during the Great Depression unemployment peaked at 25%, during the GFC it was “only” 10 percent.

The problem FED faced was exacerbated by the fact that it was not only banks stashing reserves. Corporation hoarded huge amount of cash which were sitting idly on their balance sheets. Therefore, the velocity of money, which is the ratio of nominal GDP to the money supply was decreasing during the period beginning from the mid-1990s. The velocity of money refers to the frequency at which one dollar (or one unit of currency) buys goods and services included in GDP within a given time period. Falling velocity of money means entities prefer to borrow and hoard money rather than lending it out. The slow of velocity of money was the reason why money supply growth rate being higher than GDP growth rate during this period didn’t result in inflation.

The slow of velocity of money was the reason why money supply growth rate being higher than GDP growth rate during this period didn’t result in inflation. What (inverted) yield curve means

What (inverted) yield curve means

When the yield curve inverts, the rate of ten-year Treasure bonds falls below the overnight Fed funds rate which makes liquidity more expensive. Since short-term rates are higher than long-term rates, banks pay more for funding relative to long-term rates. This decreases profits of banks so that lending slows down.

Inverted yield curve is historically associated with recessions. So, for investing purposes flattening or inverted yield curve means to get out of the stock market. This is because corporate profits tend to fall during a recession which is reflected in equity prices. Add to this tight credit conditions which lead to an increase in corporate defaults, and you have strong reasons for the bearish stock market.

This is in line with the author’s thesis that the yield curve has been a more accurate gauge of the monetary policy than the level of interest rates. What I mean here is that though increasing (decreasing) interest rates are associated with tight (easy) monetary policy, it is not always the case. The author gives an example of the US inflation during the 1970s and Fed’s response to it by increasing the rates. Monetary policy at that time was considered to be tight because interest rates were increasing. But inflation didn’t fall in response to the Fed’s actions which doesn’t happen if the monetary policy is really tight. In contrast to nominal rates, real interest rates were dropping because inflation rate was increasing faster than Fed was raising the policy rate.

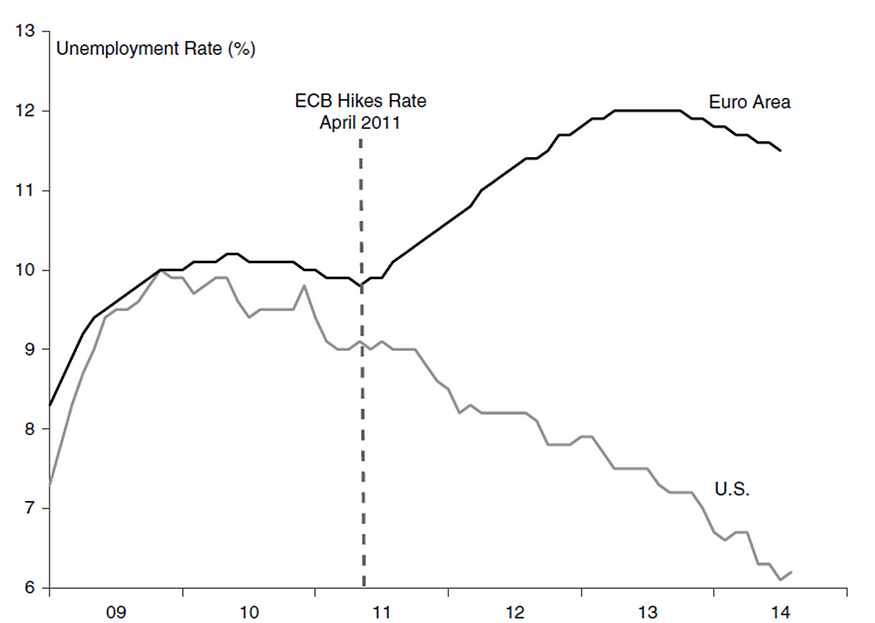

European Central Bank’s (ECB) response to the consequences of the 2007–2008 financial crisis provides another example which demonstrates that interest rates are not a reliable measure of the monetary policy being accommodative or tight. During the early-2010s the market participants were thinking of ECB policy being accommodative because interest rates were low. But as the chart below shows the credit in the Eurozone continued to shrink throughout the period despite the interest rates being very low. As R. McGee says, the relationship of low interest rates with accommodative money policy doesn’t work in a deflationary environment. The contraction of the whole banking system, the fall in the inflation and money growth rate are the signs showing that monetary policy is not accommodative but tight.

As R. McGee says, the relationship of low interest rates with accommodative money policy doesn’t work in a deflationary environment. The contraction of the whole banking system, the fall in the inflation and money growth rate are the signs showing that monetary policy is not accommodative but tight.

Debt-deflation dynamics

Since none of the advanced economies, excluding Japan, fell to deflation after World War II, most central banks don’t see it as risk and have “anti-inflation bias”. In countries experiencing hyperinflation, such as Germany, this bias is especially strong because inflation fears are still in the “social psyche”.

What Japanese economy went through in the 1990s challenged this central bank “folklore”. The point is that debt-deflation environment requires a different monetary policy response even if that response would be considered prodigal under normal economic circumstances. Large fiscal deficits and highly accommodative monetary policy are usually avoided by central banks in a normal economy with the stable inflation rate. However, in a debt-deflation environment easy monetary policy and fiscal deficit are required to offset the dramatic fall in money multiplier.

This is especially salient when we look at FED’s and ECB’s actions post-crisis. Fiscal profligacy of the US continued until 2013. Only after the economy was into recovery several years, fiscal austerity was implemented. On the other hand, ECB started to pursue austerity in the second quarter of 2011. Hiking rates in 2011 April sent European economy into another recession by the end of the year. The diametrically opposite fiscal policies affected the economy which is glaring when we look at the labor market. When ECB raised the rate in 2011, Europe’s unemployment rate, though still higher than US’s, but was close to it. ECB’s austere fiscal policy damaged European economy, and as a result, unemployment rate increased. At the end of 2013, unemployment rate of 6% in the US was half of that in Europe.

The diametrically opposite fiscal policies affected the economy which is glaring when we look at the labor market. When ECB raised the rate in 2011, Europe’s unemployment rate, though still higher than US’s, but was close to it. ECB’s austere fiscal policy damaged European economy, and as a result, unemployment rate increased. At the end of 2013, unemployment rate of 6% in the US was half of that in Europe.

This once again confirms the main point. When you are facing deflation, and not inflation, aggressive monetary and fiscal policy is what the economy needs. This is the environment where flooding the economy with the money is not irresponsible but prudent. This is the point when the expansion of central bank balance sheet and massive money printing are required.