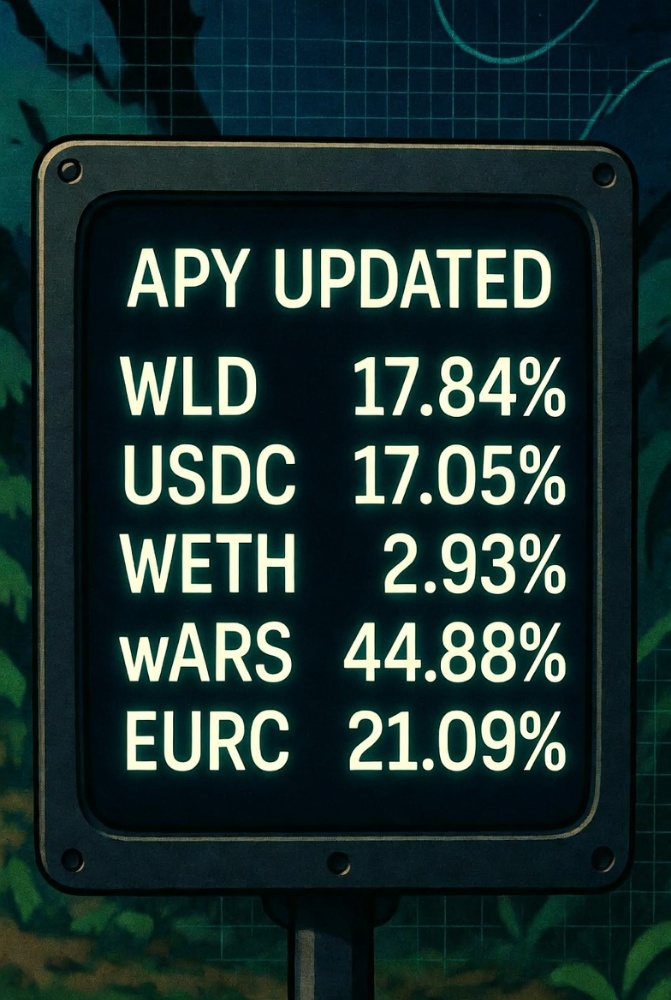

Dividend yield and 10-year Treasury yield

Dividend yield and 10-year Treasury yield

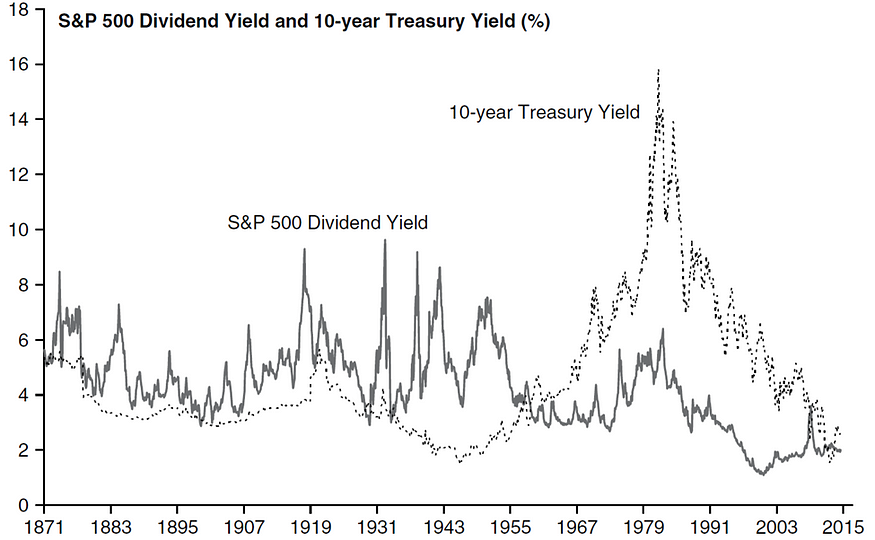

There has been a relationship between bond yields and dividend yields historically. The chart below shows that the dividend yield has been higher than 10-year yield until 1960s when the relationship changed. The anchor for equity valuation during that period was the dividend yield: when the yield was higher than the bond yield, it would make sense to buy equities because they were considered undervalued. As already explained, in the pre-Keynesian world bond yield volatility was insignificant because inflation was close to zero. However, in the era of fiat money inflation soared which was much worse for bonds than equities. In the late 1950s 10-year yield rose above the dividend yield. Though this signaled that equities were overvalue, it this was followed by one of the strongest stock bull markets. It means that something changed in the dividend yield — Treasury yield relationship.

In the late 1950s 10-year yield rose above the dividend yield. Though this signaled that equities were overvalue, it this was followed by one of the strongest stock bull markets. It means that something changed in the dividend yield — Treasury yield relationship.

Pre-World War II world, when a deflation was not an occasional phenomenon, the source of yield for investors was the dividend yield. Since deflation is detrimental to the stock market, investors couldn’t rely on the stock price appreciation. So, to incentivize investors to invest in equities, the dividend yield had to be higher than the bond yield.

Another factor explaining the shift in this relationship is how equities and bonds change their value in a highly inflationary environment. Bonds will depreciate more in real value because their maturity is fixed. This implies that the bond yield has to increase to offset the loss due to inflation. Conversely, dividends don’t have an expiry date. Therefore, they can rise as response to inflation. Stock prices can also increase in an inflationary environment which suggests that the dividend yield can remain the same and still compensate investors for inflationary losses. The result is what we already stated above — the dividend yield remained constant while the Treasury yield rose in the Keynesian world.