Great Photographers of the 20th Century

The heart of 20th century photography is inescapably in its reportorial and documentary images. Photo reporting revolutionized media. The Leica, the Rolleiflex, then the Nikon F. Photographic reporting infiltrated every square mile of the accessible world. The greatest of these reporters combined artistic vision with a photographic mission.

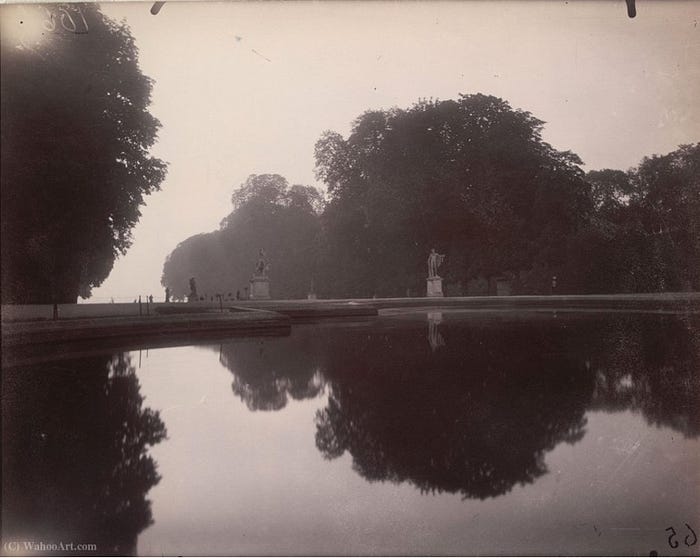

Eugene Atget (1857–1927)

Empty Street

Empty Street

You could almost call Eugene Atget the first stock photographer, but that would be selling him terribly short. Unknown and unheralded for most of his career, he sold pictures of the vanishing old Paris, often for use as references for painters. He amassed thousands of images over his career, all with a compositional sensitivity and immediacy that remains dynamic even today. Berenice Abbot first visited him in 1925, along with Man Ray, and promoted his work for the rest of her life, eventually selling her collection of Atget pictures to the Museum of Modern Art in 1968.

Atget is placed in the canon largely because of Abbott’s championship of him, which attained him recognition and influence while basically an amateur. He used photography with great artistry to pursue a mission.

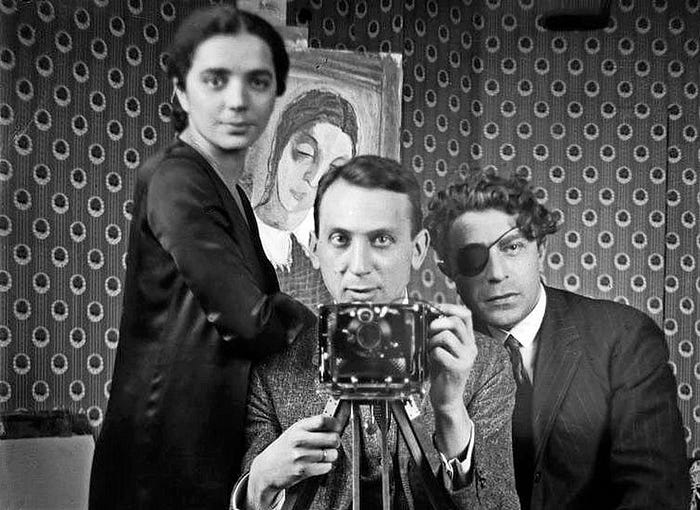

Andre Kertesz (1894–1985)

The Eiffel Tower, 1929

The Eiffel Tower, 1929 Self-portrait with friends, Paris, 1928

Self-portrait with friends, Paris, 1928

Andor Kertész was raised in Hungary. He left for Paris in 1925 to study photography, where he changed his name to André and became involved with a circle of other Hungarians and a network of prominent artists — Chagall, Mondrian, the writer Colette and filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein.

He then migrated to the U.S., where he lived for the next 55 years working as a professional photographer. He nevertheless described himself as an amateur: “I am an amateur and intend to remain one my whole life long. I attribute to photography the task of recording the real nature of things, their interior, their life.” In fact, that is what he was: an amateur at heart. He spoke through his photography, never really mastering either French or English. Photography was his all-encompassing language.

Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894–1986)

Bobsled Race, 1906

Bobsled Race, 1906 Sleep Club

Sleep Club

Jacques Henri Lartigue — his name a combination he adopted from his father’s and his own given name — was, in a way, a child photographer for his entire life. His work has an innocence, freshness and enthusiasm that no other 20th century photographer can imitate. He started taking pictures at age 7 and lived to be 92. At the age of 69, his boyhood pictures came to the attention of John Szarkowski, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art. His exhibit in 1963 made his name for the century.

Like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Lartigue was born to a prosperous family. Like Cartier-Bresson, he was also a painter. In middle age, he had to sell his paintings to make a living.

He evidently loved women. So many of his pictures are intimate and adoring images of all aspects of the female persona, from his nannies, to glamorous fashion models, to social matrons and his mistresses. There is no one like him in the century.

Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004)

Lourdes, France, 1958

Lourdes, France, 1958 A Propos de Paris

A Propos de Paris

Reporting and documentary work were the heart of 20th century photography, and Henri Cartier-Bresson is generally acknowledged as the finest of the photo-reporters.

For Harold Bloom, Shakespeare was the center of the Western literary canon. To me, Cartier-Bresson is Shakespeare’s counterpart for 20th century photography. Like Shakespeare, he was one the century’s finest pure artists. And, like Shakespeare, he covered the entire spectrum of the human condition, from war, to human disasters, to politics, to the arts. From the rich of high society, to the poor and forgotten. His work combines the precise, sophisticated compositions of a classically taught painter (he was trained as a boy in painting and sculpture) with a deep humanism and conscious libertarianism.

Cartier-Bresson’s focus on The Decisive Moment was, of course, his hallmark. The term was originally the English title of his first book (supplied by Dick Simon of Simon & Schuster), published in French as “Images à la Sauvette “ — more literally Images on the Run or Stolen Images. But he adopted the ‘decisive moment’ for himself. In his second book, The World of Henri Cartier-Bresson, he notes, “Of all forms of expression, photography is the only one which seizes the instant in its flight.” Critics have called him a “marksman” — not in the sense of the aggressive paparazzi, but more in the sense of someone who pinpoints the exact moment, and the exact vantage point, at which to press the shutter.

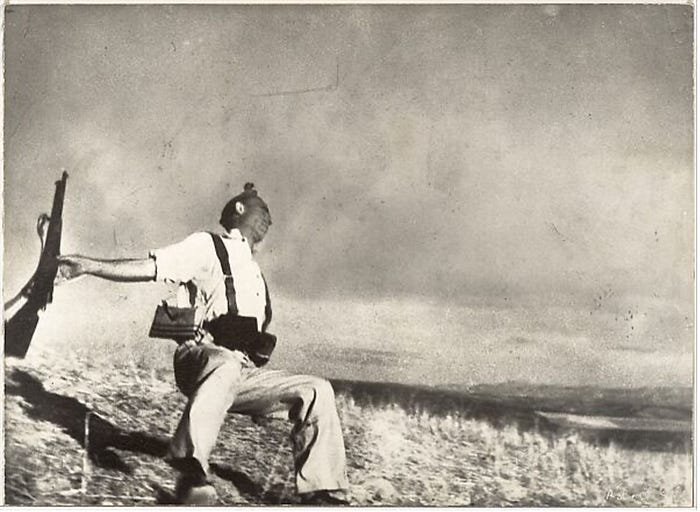

Robert Capa (1913–1954)

Death of a Loyalist Solider, 1936

Death of a Loyalist Solider, 1936 D-Day, 1944

D-Day, 1944

War photography is a universe of its own. In the 20th century, it was transformed from the sober, static documentation of Matthew Brady into the daring and intimate work of Robert Capa and his peers. Capa’s work, however, is probably the most iconic and memorable. From his coverage of the Spanish Civil War (including the controversial Death of a Loyalist Soldier, which evidence suggests was probably staged) to his D-Day work (he apparently took 111 shots, but only 11 survived), his photographs are essential to 20th century history. Capa co-founded the Magnum Photos, a cooperative agency for freelance photographers, with Henri Cartier-Bresson and others. His work is emblematic of the modern war photographer — immediate, present in the fighting, and emotionally charged. Capa died by stepping on a land mine in Indochina in 1954. He was 40 years old.

Berenice Abbott (1898–1991)

Blossom Restaurant, 1935

Blossom Restaurant, 1935 Penn Station, New York, 1936

Penn Station, New York, 1936

Berenice Abbot moved to New York at the age of 20, where she studied painting and sculpture for three years before moving to Paris. There she was a darkroom assistant at Man Ray’s portrait studio. Impressed by her work, Ray let her use his studio for her portraits, which were the legacy of her Paris years. She exhibited with Ray and Andre Kertész. Ray also introduced her to Eugène Atget’s work, and in 1927 she convinced Atget to sit for a portrait. Atget died soon afterward, and Abbott acquired a large part of his prints and negatives. She championed his work for the rest of her life.

Seeking a publisher for Atget’s images, she returned to New York City in 1929. She soon realized that New York was as great a subject as Atget’s Paris, but for opposite reasons: Atget photographed the disappearing old Paris, while Abbott decided to photograph the transformative era of New York, then emerging as a world center.

She remained in New York for the rest of her life. Her images are unadorned “straight photography.” She went so far as to dismiss Steiglitz’s work as “superpictorial,” the opposite of the “photo-documents” she wanted to create. She was also an innovator in the craft of photography itself, and interested in scientific photography. For MIT, she created textbook illustrations of waveforms and stroboscopic images of moving objects. The range and quality of her work established her as preeminent in the American mid-century.

W. Eugene Smith (1918–1978)

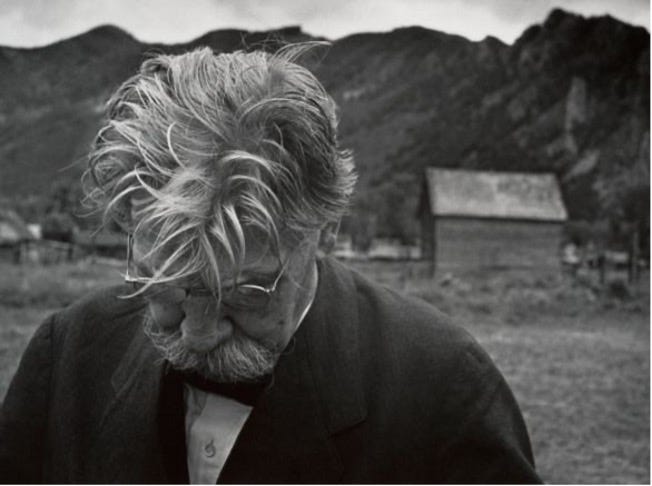

Albert Schweitzer, 1954

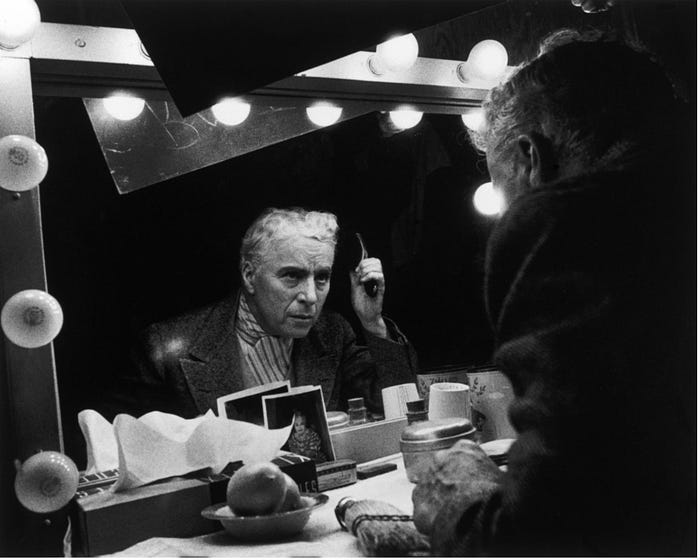

Albert Schweitzer, 1954 Charlie Chaplin during the shooting of Limelight, 1952

Charlie Chaplin during the shooting of Limelight, 1952

Gene Smith was a difficult, quirky personality. Fired from several major jobs, he persisted as one of the leading photographers of social conscience. Most importantly, perhaps, he was the exemplar of the reportorial photo essay. His work for Life Magazine — which as an institution could itself qualify as a leading member of the 20th century canon — is perhaps his great legacy.

His best work includes his essay on Albert Schweitzer, his two-year essay on the steel industry in Pittsburgh, and of course his late work documenting the industrial mercury poisoning in Minamata, Japan. He died at the age of 60.

In advancing the art of photography itself, aside from his genius for the photo essay, Smith’s printing was one of his greatest strengths. But he hated the darkroom. As he wrote Press in 1977, “…I absolutely despise printing… I know the print I want, and know I’ll probably get it, but it’s sheer drudgery. My formula for successful printing remains ordinary chemicals, an ordinary enlarger, music, a bottle of Scotch, and stubbornness.”

Diane Arbus (1923–1971)

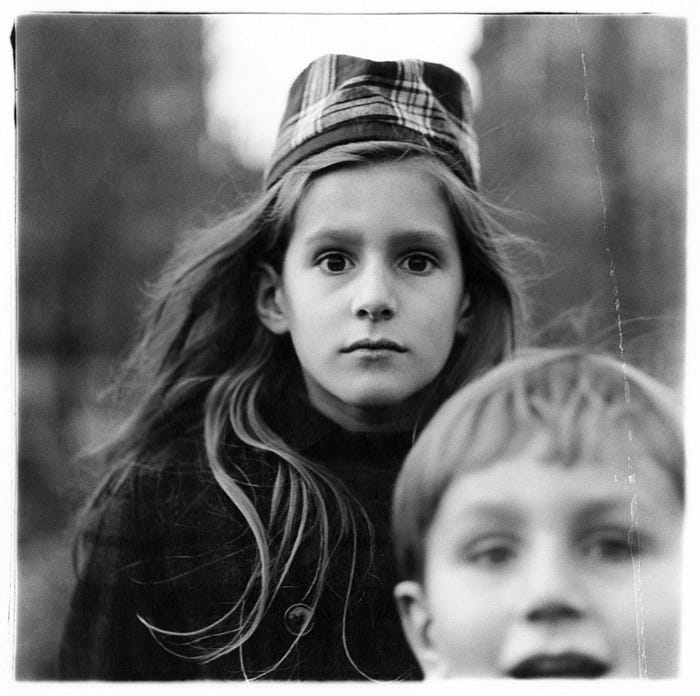

Untitled

Untitled Girl in a Watch Cap, NYC, 1965

Girl in a Watch Cap, NYC, 1965

In 1972, the Museum of Modern Art mounted a one-woman retrospective show of Diane Arbus’s work, producing the inverse effect of Edward Steichen’s Family of Man in 1956. Instead of the shared humanity of a globalizing world, her work, in Sontag’s opinion, atomized humanity and revealed it as horror. Arbus went out of her way to find the misfits, the emotionally distressed, the ugly. She didn’t photograph them on the sly — she addressed them directly and unassumingly, letting them reveal themselves, usually looking straight into the camera. The paradox here is how this interior world, apparently full of pain and alienation, is all around us. The question is, why and how does Arbus see it to the exclusion of all else? See it when we do not see it? She is canonical in this ability — her talent for finding this subject matter where others do not, for using the camera to reveal her inner self and her compulsions.

She famously wrote, “Photography was a license to go where I wanted to go and do what I wanted to do.” That place was not one that many would like to follow, but her work shows the camera’s ability to discover almost anything. Arbus suffered from depression throughout her life. She killed herself in 1971.

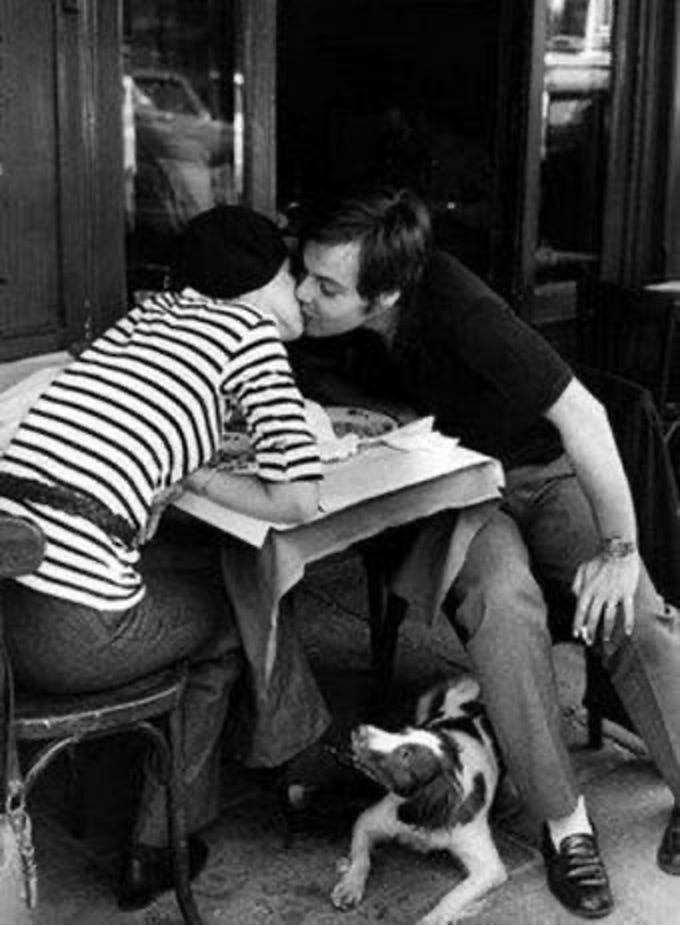

Robert Frank (1924–2019)

Couple, Paris, 1952

Couple, Paris, 1952 New Orleans Trolley, The Americans, 1958

New Orleans Trolley, The Americans, 1958

Born in Zurich, Robert Frank left in 1947 because he outgrew what he called “the smallness of Switzerland.” He worked for a while at Harper’s Bazaar, but the job wore him out and he went on to independent work, back and forth from still photography to video.

He had an outsider’s temperament his entire life. Things were going fairly smoothly in the evolution of photography’s worldview when Frank threw a rock through the glass in 1958. His publication of The Americans, funded by a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation, is generally considered the most influential single photography book of the century.

The Americans violated all the rules. Pictures were fuzzy, horizons tilted. Practical Photography dismissed it all as “meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons and general sloppiness.” Most important, Frank challenged the American myth itself, revealing the social disparities, loneliness and suspicions behind the façade of American exceptionalism. He was a Swiss Alexis de Tocqueville with a camera.

Unlike photojournalism to this point, Frank’s pictures lend themselves to literary deconstruction. In the trolley photo above, for instance, not only is segregation graphically obvious, but the generational transmission of prejudice is clear — from the sneering adult on the left to the innocent white children next to her. A white hand and a black hand hang from the open windows. The four central passengers look at us questioningly. This is a world out of equilibrium.

Frank’s sour vision is different from Diane Arbus’s. Arbus’s pictures reveal a dystopia that seems to be visible only to her. Frank pulls the curtain back on a part of the world that we all share, but would prefer to keep hidden.

Apologies

This article is just a first cut at a subject far larger than anything I can do justice to. Looking back at it, I feel a little apologetic to have made the attempt — in the mode of, “I don’t know anything about art, but I know what I like.”

I have left out dozens of my favorites, including Aaron Siskind, Harry Callahan, Alfred Eisenstadt, Margaret Bourke-White, Bill Brandt, Bruce Davidson, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Robert Doisneau, Elliot Erwitt, Bill Wegman, Fan Ho, Irving Penn, Marc Riboud, Minor White… The list goes on. And what about the great non-professional images? The picture of the earth rising above the rim of the moon, taken by astronaut William Anders in 1958? Harold Bloom concluded his Western Canon with 37 pages of names of other writers whom he didn’t include in his canon.

So the question is, is this a fruitless effort, in the sense of, could it ever reach a resolution? Is it misguided, in the sense of asking the wrong questions?

One reason I think it may be valuable is because of the implied next question: Could we create a canon of 21st century photographers? To me, the 20th century mapped out the basic territory of what still imagery can do with photography as a print-on-paper medium. Despite the explosion of digital photography, serious photography today seems simply to be wearing deeper ruts in the paths laid down from 1901 to 2000. Looking back at the last century, the explorers of this new art were the trailblazers who opened up another new world. We continue to populate that world, but all its territory seems to have been mapped already.

This does not diminish the value and pleasure that we all get by taking pictures, of course. Photography as the art of seeing is now as permanent an undertaking as writing, painting or any of the other arts. For most of us, we do for its own sake, and always will.