URBAN PLANNING IN BARCELONA

LOCATION

•Barcelona, situated in the northeast corner of the Iberian Peninsula, is bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the east, the Collserola Mountains to the west with its highest peak, Tibidabo (512m), the Besòs River to the north, and the Llobregat River to the south. Its carefully defined and thus easily defensible terrain serves as the most accessible gateway to Europe from the rest of the peninsula.

In the 5th century AD, following the fall of the Roman Empire, the city witnessed a series of conquests. During the Middle Ages, it evolved as the center of a region known as Catalonia, becoming more intricate. In 1260, expanded walls were constructed, and in the 15th century, further expansions included the Raval district. The area outside the walls, known as the plain, was dedicated to agricultural activities to sustain the city's livelihood.

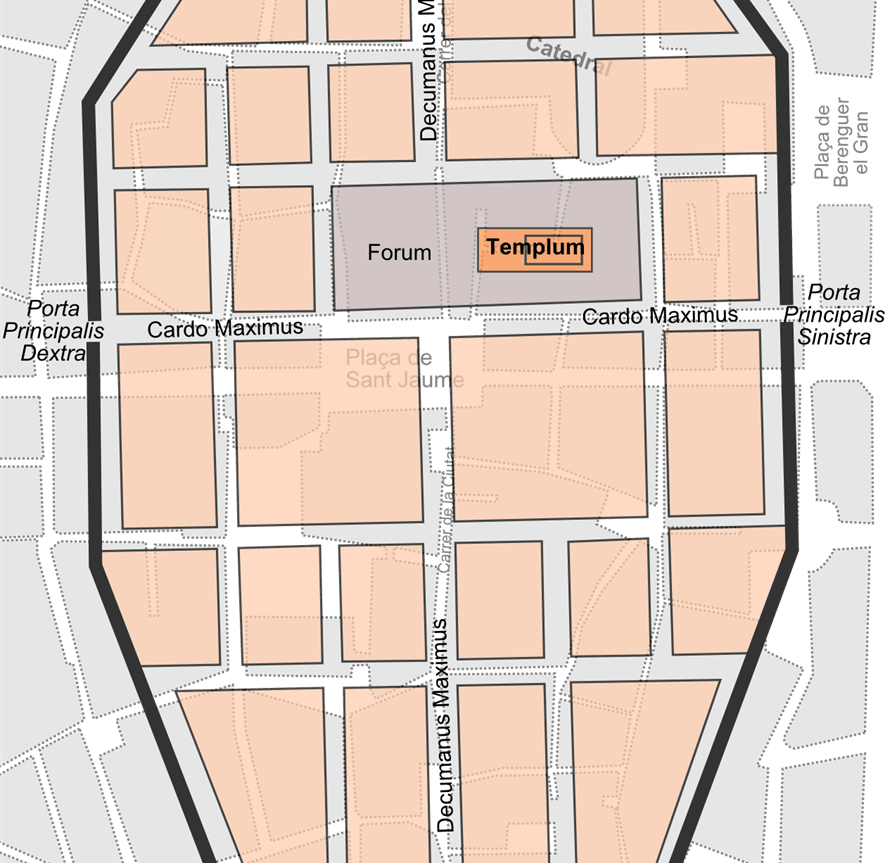

According to information obtained from archaeological remains, human settlement has existed in the region since around 5000 BC. The origins of the city trace back to the establishment of a small medieval town with a grid plan called Barcino by the Romans in 15 BC.

The Emergence of the Need for Urban Renewal

•Barcelona has never been able to escape invasions since its foundation. Therefore, the city has been frequently surrounded by walls for protection. The construction of city walls began in the Roman period, and as the city grew, new walls were built (in the 13th century, the city was surrounded by a total of 5,000 meters of walls). However, especially in 1714, Philip V surrounded the city with very tight walls both to control the city and to protect it from external attacks. Additionally, he established strong fortresses (Ciutadella) at two points to both keep the city under surveillance and monitor potential external threats. During this period, speaking Catalan was prohibited in the city, Catalan universities were closed, and many restrictions were imposed on cultural life. In this era, the development outside the city walls was strictly forbidden. This was not only to better protect the city from external attacks but also, perhaps more importantly, to keep the population under control. In the area outside the walls, even agriculture was not allowed; it was kept entirely as vacant space.

Cerdà’s utopian plan for Barcelona

•As soon as the wall’s demolition was announced, plans began for an expansion of the city. In 1855, the central Spanish government approved a plan by architect Ildefons Cerdà.

•

•Cerdà was horrified by the conditions of the working class in Barcelona and set out to make his extension of the city — the Ensanche in Spanish, or in Catalan, as the district is still known today, the Eixample — a model of orderly, clean, safe, hygienic urban living.

•First, he took what was, for the time, an exceptionally holistic view of urban quality. He wanted to ensure that each citizen had, on a per capita basis, enough water, clean air, sunlight, ventilation, and space. His blocks were oriented northwest to southeast to maximize daily sun exposure.

•

•And second, his plan embodied what is — then and today — a striking egalitarianism. Each block (manzana) was to be of almost identical proportions, with buildings of regular height and spacing and a preponderance of green space. Commerce was to take place on the ground floor, the bourgeoisie were to live on the floor above (rather than in mansions at the edge of town), and the workers were slated for the upper floors. In this way, they would all share the same streets and public spaces, exposed to the same hygienic conditions, reducing social distance and inequality.

•Originally, each of Cerdà’s blocks was to have buildings on just two sides (sometimes three), occupying less than 50 percent of the total area, with the bulk of the interior space devoted to gardens and green space. The buildings were to be low enough (no more than 20 meters tall and 15 to 20 meters deep) to allow for almost continuous sunlight in the interiors during the day.

•The goal was to combine the advantages of rural living (green space, fresh air and food, community) with the advantages of urban living (commerce, culture, free flow of goods and ideas).

What happened to Cerda’s plan?

•In its initial form, it won approval from the (progressive) Spanish government and Barcelona city hall. But in 1856, a conservative shift in government led to the appointment of a new city council, which ignored the plan and held a competition to select its own plan.

•

•Even as, in 1859, the royal government was approving Cerdà’s plan, the city government announced the winner: a plan by architect Antoni Rovira.

•The Rovira plan reflected the conservative tastes of the city’s wealthy and powerful. It was more traditional, built around the Old Town center, with a hierarchy of wider to smaller streets. It made room for grand monuments and architecture. And it segregated the bourgeoisie in the center from the workers on the periphery. The Spanish government ignored Rovira’s plan and pushed forward with Cerdà’s, but in Barcelona, the Catalan-friendly city government and the working classes alike saw it as an imposition from outside. Buildings were often built on all four sides of the blocks’ interiors, rather than two. By 1890, the buildings occupied an average of 70 percent of the block’s area. By 1958, the total volume of space on the manzanas occupied by buildings had grown from Cerdà’s envisioned 67,200 square meters to 294,771. The blocks have only been built up further since.

•In recent years, Barcelona has been grappling with the consequences of its spiraling success, familiar to many growing cities: It is overrun by tourists, real estate prices are rising due to foreign speculation, gentrification is pushing out longtime residents, and there are too many cars, bringing with them noise, air pollution, and congestion.