Broadband in the EU Member States PART-1

Hello everyone,

Despite progress, not all the Europe 2020 targets will be met

About the report

Broadband, meaning faster, better quality access to the internet, is becoming increasingly important not only for business competitiveness, but also for helping social inclusion. As part of its Europe 2020 strategy, the EU has set targets for broadband, including fast broadband availability for all Europeans by 2020. To support these objectives, the EU has made some 15 billion euro available to Member States in the period 2014-2020. We found that broadband coverage has generally been improving across the EU, but that the Europe 2020 targets will not all be achieved. Rural areas, where there is less incentive for the private sector to invest, remain less well connected than cities, and take up of ultra-fast broadband is significantly behind target.

Executive summary;

About broadband

- Broadband is the common term used to mean faster internet speeds and other technical characteristics that make it possible to access or deliver new content, applications and services. An increase in the importance of digital data now means that good internet connections are essential not only for European businesses to remain competitive in the global economy, but also more widely for promoting social inclusion.

- As part of its Europe 2020 strategy, in 2010 the EU set three targets for broadband: by 2013, to bring basic broadband (up to 30 Megabits per second, Mbps) to all Europeans; by 2020, to provide all Europeans with fast broadband (over 30 Mbps); and by 2020, to ensure take-up by 50 % or more of European households to ultra-fast broadband (over 100 Mbps). To support these objectives, the EU has implemented a series of policy and regulatory measures and has made some 15 billion euro available to Member States in the period 2014-2020, through a variety of funding sources and types, including 5.6 billion euro in loans from the European Investment Bank (EIB).

How we conducted our audit;

- We addressed the effectiveness of action taken by the European Commission and the Member States to achieve the Europe 2020 broadband objectives.

- The audit covered the 2007-2013 and the 2014-2020 programme periods and all the EU funding sources, including support provided by the EIB. Our audit work extended to all those parts of the Commission with significant roles to play in broadband, and the EIB. For a more detailed understanding of the national issues, we focused on five Member States: Ireland, Germany, Hungary, Poland and Italy. We also visited a range of other stakeholders (such as National Regulatory Authorities, business and telecommunications associations, consumer associations and trade unions).

What we found

- We found that broadband coverage has generally been improving across the EU, but that the Europe 2020 targets will not all be achieved. Rural areas, where there is less incentive for the private sector to invest in broadband provision, remain less well connected than cities, and take-up of ultra-fast broadband is significantly behind target.

- In terms of the three targets, while nearly all Member States achieved the basic broadband coverage target by 2013, this will most likely not be the case for the 2020 target for fast broadband. Rural areas remain problematic in most Member States: by mid-2017 14 had coverage in rural areas of less than 50 %. For the third target, take-up of ultra fast broadband, only 15 % of households had subscribed to internet connections at this speed by mid-2017, against a target of 50 % by 2020. Despite these problems, if their plans are implemented as intended, three of the five examined Member States may be in good position to achieve the Commission’s objectives for 2025, one of which is that all households should have access to ultra-fast broadband, upgradable to 1 Gbps. The Commission’s support was positively assessed by the Member States but the monitoring is uncoordinated across Directorates-General.

- All Member States had developed broadband strategies, but there were weaknesses in the ones we examined. Some Member States were late in finalising their strategies, and their targets were not always consistent with those in Europe 2020. Not all the Member States had addressed the challenges related to their legacy internet infrastructure (their telephone infrastructure), with potential implications for adequate speed in the medium and long term.

- Various factors limited Member States’ progress towards meeting their broadband targets. Financing in rural and sub-urban areas was not properly addressed in three of the Member States we examined, and a major EIB project supported through the European Fund for Strategic Investments did not focus on those areas where public sector support is most needed. We found that the legal and competitive environments posed problems in two Member States. In addition, we found a lack of coordination across programme periods in one Member State.

What we recommend

- Digital data via the internet is playing an increasingly large role in the lives of citizens, government and business. For Europe to remain competitive in the global economy, good levels of internet speed and access, as provided by broadband, are essential. For example:

- an increase of 10 % in broadband connections in a country could result in 1 % increase in GDP per capita per year1;

- a 10 % increase in broadband connections could raise labour productivity by 1.5 % over the next five years2; and

- investments in broadband will also help deliver quality education, promote social inclusion and benefit rural and remote regions.

Some stakeholders3 consider that broadband is so important that it should be seen as an essential utility, alongside other utilities such as road, water, electricity and gas.

2.The term ‘broadband’, in the context of internet access, does not have a specific technical meaning but is used to refer to any infrastructure for high-speed internet access that is always on and faster than traditional dial-up access. The Commission has defined three categories of download speeds:

- ‘Basic broadband’ for speeds between 144 Kbps and 30 Mbps;

- ‘Fast broadband’ for speeds between 30 and 100 Mbps; and

- ‘Ultra-fast broadband’ for speeds higher than 100 Mbps.

3.A broadband access network is generally made of three parts: the backbone network, middle mile and the last mile connections to the end users (see Figure 1)4.

Figure 1

Segments of a broadband network

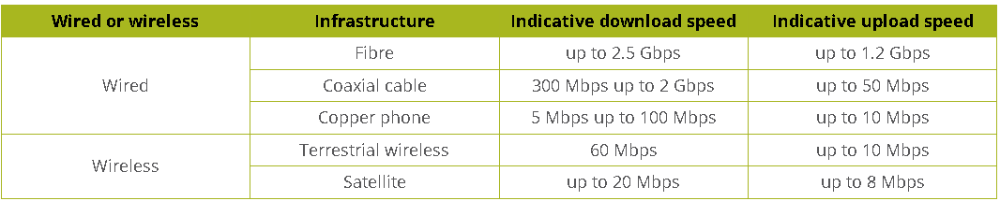

4.In assessing internet speed, there is an important distinction between download and upload speeds. Download speed refers to the rate data is received from a remote system, such as when browsing the internet or streaming videos; upload speed refers to the rate data is sent to a remote system, such as when video-conferencing. Other technical characteristics are becoming increasingly relevant for the provision of certain services (such as videoconference, cloud computing, connected driving and e-health). The type of infrastructure used defines the upper limit of the connection speed. There are five types of infrastructure that can deliver broadband services: optical fibre lines, coaxial cable, copper phone lines, terrestrial wireless (antenna sites/towers) and satellite (see Table 1). Due to rapid technological development, other technologies are also becoming capable of delivering fast broadband services (see Box 1).

Table 1

Broadband infrastructure types and current commercial technology

Source: ECA analysis based on Acreo Swedish ICT.

Box 1 Technological developments

- Hybrid internet solutions combine the copper phone network and the 4G mobile network to increase speed to customers, using a specific gateway (a type of modem). This solution is already in use in Belgium and the Netherlands with speeds of 30 Mbps in previously under-served areas.

- The satellite industry is currently delivering the next-generation satellite broadband. Two recent innovations are the high-throughput satellites and the non-geostationary orbit satellites. By using these types of satellites, connections over 30 Mbps may be offered in the future to a larger number of rural or remote customers.

- 5G, 5th generation mobile networks are the next wireless telecommunications standards. 5G planning aims at higher capacity than current 4G, allowing a higher density of mobile broadband users, and supporting device-to-device, more reliable, and massive machine communications. 5G has three elements: (1) enhanced mobile broadband, (2) massive Internet of Things, (3) mission critical services (such as self-driving cars). 5G requires a middle mile infrastructure based on fibre making 5G a complement to, but not a replacement for, high speed broadband networks close to the end user.

5.Each of these technologies has its own characteristics, as well as costs and benefits, with existing copper phone being the cheapest technology for a lower speed, and fibre delivering the highest speed at a higher cost. Future applications related to the Internet of Things (see Box 2) will require higher speeds, scale and reliability from these networks5. In general, the roll out of technology which provides higher speeds is more expensive than technology delivering lower speeds although maintenance costs are lower. In addition, operators’ management costs are also likely to be reduced progressively as legacy networks are decommissioned.

Box 2 The Internet of Things

The Internet of Things is a network of physical devices with the ability to transfer data without the need for human-to-human or human-to-computer interaction. Examples are: Smart homes (e.g. controlling thermostat, lights, music), Smart cities (e.g. controlling street lights, traffic lights, parking), self-driving cars, Smart farming (combining data on soil moisture or pesticide usage with advanced imaging).

EU policies for broadband

6.Launched in 2010, Europe 2020 is the EU’s long-term strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth6. It contains seven flagship initiatives. One of these, “A Digital Agenda for Europe”7, sets out targets for fast and ultra-fast internet to maximise the social and economic potential of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), most notably the internet, for EU citizens and businesses. The Digital Agenda, updated in 20128, sets out three objectives for broadband:

- by 2013, to bring basic broadband to all Europeans;

- by 2020, to ensure coverage of all Europeans with fast broadband (> 30 Mbps); and

- by 2020, to ensure take-up of 50 % or more of European households to ultra-fast broadband (> 100 Mbps).

The first two targets focus on supplying certain speeds, while the third relates to the demand by users. These targets have become a reference for public policy throughout the EU, and have given direction to public and private investment. The comparable target for the USA is in Box 3.

Box 3 Broadband targets in the USA

In the USA, the National Broadband Plan “Connecting America" was adopted in March 2010 and recommended that the country adopt and track six goals for 2020, the first of which was "At least 100 million U.S. homes should have affordable access to actual download speeds of at least 100 megabits per second and actual upload speeds of at least 50 megabits per second". Thus the objectives did not include 100 % of the population and the targets specified actual upload and download speeds.

7.In 2010, the Commission also set out a common framework for action at EU and Member State levels to meet these targets. Requirements for Member States included the need to: (i) develop and make operational national broadband plans by 2012; (ii) take measures, including legal provisions, to facilitate broadband investment; and (iii) use fully the Structural and Rural Development Funds.

8.In September 2016, the Commission identified in a Communication commonly known as the ‘Gigabit Society for 2025’9 three strategic objectives for 2025 that complement those set out in the Digital Agenda for 2020:

- Connectivity of at least 1 gigabit10 for all main socio-economic drivers (such as schools, transport hubs and the main providers of public services);

- all urban areas and all major terrestrial transport paths to have uninterrupted 5G coverage; and

- all European households, rural or urban, to have access to internet connectivity offering a download speed of at least 100 Mbps, upgradable to Gigabit speed.

EU financial support to broadband infrastructures

9.The European Commission estimated in 2013 that up to 250 billion euro will be required to achieve the 2020 broadband targets11. However, the re-use of existing infrastructure and effective implementation of the Cost Reduction Directive12 could bring down these costs13.

10.The telecommunication sector is the major private investor in broadband infrastructures. Some segments of the market, such as rural areas, are not attractive to private investors. Financing from the public sector, whether national, regional or municipal, is required to provide acceptable broadband connectivity in these areas. The EU is an additional source of financing complementing other sources of public funding (national regional or local) in areas subject to market failure. In some Member States it can constitute the main source of public funding.

11.For the 2014-2020 programme period, almost 15 billion euro, including 5.6 billion in EIB loans, is available to Member States from the EU for supporting broadband, a significant increase over the 3 billion euro for the 2007-2013 period. This represents around 6 % of the total investment needed. There are five main sources of funding (see Table 2).

Table 2

Summary of funding sources for the programme periods 2007-2013 and 2014-2020

EFSI amounts are as of end of June 2017.

Source: ECA analysis based on Commission and EIB data.

12.The Commission, together with the Member States, manages the Structural Funds (ERDF, EAFRD). The Commission also provides a guarantee in support of projects financed by the EIB. The EIB is responsible for the management of its own loans and, the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI). The Commission manages the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) and part of the available funding for broadband under CEF is envisaged to be invested in the Connecting Europe Broadband Fund (CEBF). The CEBF will be managed by an independent Fund Manager and mandated to act according to the terms of reference agreed by the EIB, the Commission and the other funding partners.

Audit scope and approach

13.The audit addressed the effectiveness of the action taken by the Commission, the Member States and the EIB to achieve the Europe 2020 broadband objectives. This is particularly relevant as the 2020 deadline is approaching and as the Commission has communicated new objectives for 2025. To do this, we examined:

- whether the Member States are likely to achieve the Europe 2020 broadband objectives and whether the Commission monitored these achievements;

- whether the Member States had developed appropriate strategies to achieve these objectives; and

- whether the Member States had effectively implemented their strategies – including the measures and financing sources chosen (including the EIB) and the regulatory, competitive and technological environments established.

We also examined the Commission’s support in relation to these three topics.

14.This audit covered all the funding sources listed in Table 2: ERDF, EAFRD, CEF, EFSI, EIB loans and CEBF. It focused on five Member States: Ireland, Germany, Hungary, Poland and Italy. These Member States represent around 40 % of the EU population, and were selected to provide reasonable balance in terms of geographical spread and aspects of broadband coverage, such as rurality and subscription cost. The audit covered the 2007-2013 and the 2014-2020 programme periods.

15.At EU level, the audit covered all the Commission Directorates-General with significant roles in broadband14, as well as the EIB with regard to the EFSI and the CEBF. The audit team visited various relevant stakeholders and NGOs in Brussels and the Member States: telecommunication associations, consumer associations and enterprise associations. Visits in the Member States examined included ministries responsible for setting up and implementing the broadband strategy, bodies responsible for managing the programmes funded through the ESI funds, Broadband Competence Offices, and National Regulatory Authorities. We also benefited from the input of telecommunication experts on the observations, conclusions and recommendations of this report.

Observations

Although broadband coverage is improving across the EU, some Europe 2020 targets are unlikely to be achieved

16.We reviewed the progress achieved by the Member States since 2010 against the three Digital Agenda targets (see paragraphs 6 and 7). We also took account of whether Members States were likely to achieve the 2025 targets, and assessed the Commission’s monitoring and its support to the Member States

All Member States achieved the basic broadband coverage target by 2016

Target 1: by 2013, to bring basic broadband to all Europeans

17.At the end of 2013, all Member States except the three Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) had achieved the target for basic broadband coverage. By the end of June 2016, virtually all citizens in the EU had access to basic broadband networks and 98 % of the households had access to fixed broadband connections.

Two of the five examined Member States may achieve the 30 Mbps coverage target by 2020 but rural areas remain problematic in most Member States

Target 2: by 2020, to ensure coverage of all Europeans with fast broadband (> 30 Mbps)

18.For this target, we found significant improvement in most Member States. Across the EU, the proportion of households with access to fast broadband increased from 48 % in 2011 to 80 % in June 2017. At that date, Malta had already achieved the target. However, there remain important differences between Member States: Greece and France had achieved about 50 % coverage, and a further seven Member States remained below 80 % (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

30 Mbps coverage in all Member States in 2011 and in 2017

Source: ECA analysis based on Commission data.

19.In the five audited Member States, the trend was also for increased coverage between 2011 and 2017 (see Figure 3). Through a combination of private and public investments, Hungary, Ireland and Italy have significantly increased their fast broadband coverage since 2011. In addition, these three Member States have plans to increase further this coverage in rural and sub-urban areas.

20.However, in the cases of Ireland and Italy, based on past progress and current plans, it is unlikely that the 30 Mbps will be available to all citizens by 2020. Two Member States, Hungary and Germany, could still achieve 100 % coverage of the population at 30 Mbps by 2020, based on their deployment plans. In Poland, at the end of 2017, the deployment plans did not include the coverage of 13 % of the households by 2020, primarily in sub-urban and rural areas (see paragraph 57).

Figure 3

Evolution of 30 Mbps coverage in the five examined Member States from 2011 to 2017

21.This general increase in fast broadband coverage hides a significant discrepancy between coverage in urban and rural areas. Across the EU, coverage in rural areas was 47 % of the households in 2016, against the overall average of 80 %15. Only three, relatively small or urbanised Member States, Malta, Luxembourg and the Netherlands had coverage in their rural areas equivalent to the urban areas (see Figure 4). In many Member States, rural coverage is far below the total coverage and for 14 Member States the high speed broadband coverage in rural areas is less than 50 %. Without good broadband coverage, the risk is that rural areas miss out on the economic and social benefits that can flow (see paragraph 1).

22.In France, the updated national broadband plan of 2013 aimed at a coverage of the whole population at speeds of 30 Mbps by 2022, with a coverage of 80 % of the population through fibre. However, in a report of January 2017, the French Court of Auditors questioned the relevance of the use of fibre in certain areas, since the costs of fibre are high and the implementation timing too long. France is now considering the use of other technologies such as 4G fixed wireless connections in certain areas.

Figure 4

30 Mbps coverage in rural areas compared to total coverage in 2017

Source: ECA analysis based on Commission data.

While most of the examined Member States are not likely to achieve the take-up target by 2020 …

Target 3: by 2020, to ensure take-up of 50 % or more of European households to ultrafast broadband (> 100 Mbps)

23.The availability of ultra-fast broadband is a pre-requisite for households subscribing to 100 Mbps services. However, take-up is also driven by demand and depends on multiple variables such as population age and education, subscription price, and purchasing power. Target 3 remains very challenging for all Member States. Although take-up has increased since 2013, in 2017 it remained under 20 % in 19 Member States, a long way short of the 50 % target. Across the EU, only 15 % of European households had subscribed to connections of at least 100 Mbps mid 2017 (see Figure 5). We note that Gigabit Society targets for 2025 (paragraph 8) do not include a target for take-up.

Figure 5

100 Mbps subscriptions in 2013 and 2017

Source: ECA analysis based on Commission data.

24.In the five Member States examined, take-up ranged from under 5 % to nearly 30 % in 2017. For these five Member States, with the exception of Hungary, the rate of increase in take-up exhibited since 2013 would not be sufficient to achieve the 50 % take-up target by 2020 (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

100 Mbps subscription evolution in the five examined Member States from 2013 to 2017

Source: ECA analysis based on Commission data.

… three of the examined Member States may, based on their current plans, be in good position to achieve the 2025 targets

25.The Commission’s communication of 2016 on the Gigabit Society set three strategic objectives to achieve for 2025. These objectives complement those laid down in the Digital Agenda for 2020 and require speeds of 100 Mbps up to 1 Gbps.

26.As explained above (see paragraph 20), Ireland and Italy are unlikely to achieve the 100 % coverage at 30 Mbps by 2020. However, if their current plans are implemented as intended, together with Hungary, Ireland and Italy will be better placed to achieve the 2025 targets. In these Member States, the technologies used to increase the coverage, mainly coaxial cable and fibre, enable speeds of over 100 Mbps, in some cases upgradable to 1 Gbps. The other two Member States will have to adapt their plans to reflect the 2025 targets.

The Commission’s support was positively assessed by the Member States but its monitoring is uncoordinated across Directorates-General

27.We examined whether the Commission provided the Member States with guidance on broadband and supported the Member States in the practical implementation of their plans. We assessed whether the Commission supported the Member States in monitoring their achievements, including whether the Commission encouraged the Member States to address shortcomings in relation to their achievement of broadband objectives.

The Commission’s guidance and support covered multiple issues and was continuously rolled out to improve implementation

28.The Commission provided a wide range of guidance, covering a number of different topics. This included Communications (such as the EU Guidelines for the application of State aid rules in relation to the rapid deployment of broadband networks16), explanatory guides in different fields, prepared by third parties for the Commission (such as the “Guide to High-Speed Broadband Investment”17 and “The broadband State aid rules explained, An eGuide for Decision Makers”18), as well as the dissemination of good practice. An example of helpful guidance provided by the Commission is in Box 4.

Box 4 Broadband Mapping

Mapping is a key element of planning broadband networks and provides the basis for EU State aid assessment of these projects. The mapping of broadband networks helps to target funding more effectively and facilitates planning. Poor mapping on the other hand can result in poor financial viability of both public and private investment.

Broadband mapping is the gathering and presentation of data related to the deployment of broadband. This mapping is not only linked to geo-referential visualisation; it comprises the entire process of data collection. This can be data on the deployment of broadband infrastructure itself, i.e. copper or fibre cable, and it can also be related to infrastructure, such as ducts and pipes. Additionally, broadband mapping needs to consider the actual supply of and demand for broadband services as well as existing and planned investments in broadband infrastructure.

A study for the Commission19 reviewed broadband and infrastructures mapping initiatives in Europe and around the world and developed four types of broadband mapping: infrastructure mapping; investment mapping; service mapping and demand mapping. Publicly available maps and statistics are the most visible outcomes of broadband mapping in EU Member States and are in most cases a combination of the four types of broadband mapping.

29.In addition to written guidance, the Commission provided practical technical support (e.g. JASPERS20), expertise and guidance to the Member States in different contexts (e.g. fulfilment of the ex-ante conditionalities, including mapping, as above21, and the implementation of the Operational Programmes). The Commission has also set up the European network of Broadband Competence Offices (see Box 5).

30.The five examined Member States reported to us that they assessed the formal and informal support provided by the Commission as positive.

Box 5 The European network of Broadband Competence Offices (BCO

In November 2015, the Commissioners of DG CNECT, DG AGRI and DG REGIO invited the Member States to take part, on a voluntary basis, in the setup of a network of BCOs. The intention was for each BCO to give advice to citizens and businesses and provide technical support to representatives of local and regional authorities on ways to invest effectively in broadband, including the use of EU funds.

The BCOs were set up by the end of 2016. In January 2017, the Commission set up a Support Facility which helps the BCOs in running events, workshops and training seminars, as well as managing and moderating web-based forums about relevant topics to the BCOs. The potential advantage of the BCO network is that BCOs are able to deal with a wider range of issues and tasks, including policy matters, than a technical specialist would be able to.

The Commission monitored regularly, but in an insufficiently coordinated manner

31.The Commission carries out regular monitoring on the state of play of broadband in the Member States and aggregates the information at EU level. However, there is no common monitoring across the Commission’s Directorates-General to support the achievements of the Europe 2020 broadband targets.

32.DG CNECT staff visits the Member States annually and produces market and regulatory reports such as the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) and the European Digital Progress Report (EDPR). These documents allow the Member States to compare their achievements over time and with other Member States. Although the Commission collects the relevant data and has been reporting it in the EDPR and its predecessors, the connectivity indicators reported in DESI do not include target 3 (50 % of households with subscriptions of over 100 Mbps).

33.DG REGIO’s monitoring is based on the indicators defined for each Operational Programme and takes place through the Monitoring Committees in which the Commission has an advisory role and the Annual Implementation Reports. The common output indicator defined by the Commission for ERDF spending does not allow progress against the achievement of all three Digital Agenda 2020 targets to be monitored, as it is defined as “Additional households with broadband access of at least 30 Mbps” and is not broken down between fast broadband (above 30 Mbps) and ultra-fast broadband (above 100 Mbps). This is also the case for the EAFRD, for which DG AGRI defined the output indicator as “Population benefiting from improved services/infrastructures (IT or others)”. Both for the ERDF and EAFRD, the common indicators do not distinguish between fast broadband and ultra-fast broadband.

34.Our examination of the selected Member States demonstrated a number of delays which affect the achievement of the EU 2020 targets. In the case of Ireland, since 2015 the National Broadband Plan implementation has encountered delays. In Germany, the negotiations on the virtual unbundled local access product (VULA) (paragraph 48) have been time consuming with potentially detrimental competitive effects. Finally, in the case of Poland, the Operational Programmes’ monitoring did not highlight the issue of under-use of the backbone infrastructure (paragraphs 76 to 78). At the time of the audit, none of these three shortcomings had been explicitly identified by the Commission’s monitoring, and no remedial action had been taken by the Member State authorities concerned.

https://european-union.europa.eu/index_en

![[Honest Review] The 2026 Faucet Redlist: Why I'm Blacklisting Cointiply & Where I’m Moving My BCH](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/4b90c949-f023-424f-9331-42c28b565ab0/1)