Being in Nature, For What?

Why Being in Nature Makes You Smarter, According to Neuroscientists

The scientific evidence is overwhelmingly clear: spending time outdoors boosts your brain function. So what are you waiting for?

Hendrix Prather had a rough entry to school. When the now nine-year-old started kindergarten, he struggled to focus on his ABCs and counting, chafing against the expectation that he sit still and be quiet. First grade brought more of the same. “There was a lot of discussion with his teachers about his participation in class, keeping him engaged and staying focused,” says his mother, Lindsay Prather. “He was capable, but couldn’t focus to move forward. He was labeled a problem kid.”

Lindsay pulled him out of his public school and homeschooled him for two years. Then, when Hendrix asked to return to a classroom for fourth grade, she enrolled him at a very different kind of institution: Woodson Branch Nature School in Marshall, North Carolina where she now serves as the school’s director of education. There, he spends the morning working on reading and math in the classroom, then moves outdoors for nature-based art projects, engineering assignments involving branches and rocks, and planting projects in the school garden. Best of all, though, “Now I have an hour of forest time out in nature, and I get to go to a different place every day,” Hendrix says. “It helps me focus more and get my energy out.”

“Now he’s extremely focused during his academic time,” Lindsay says. “He’s just thriving academically.”

The Evidence Is Clear

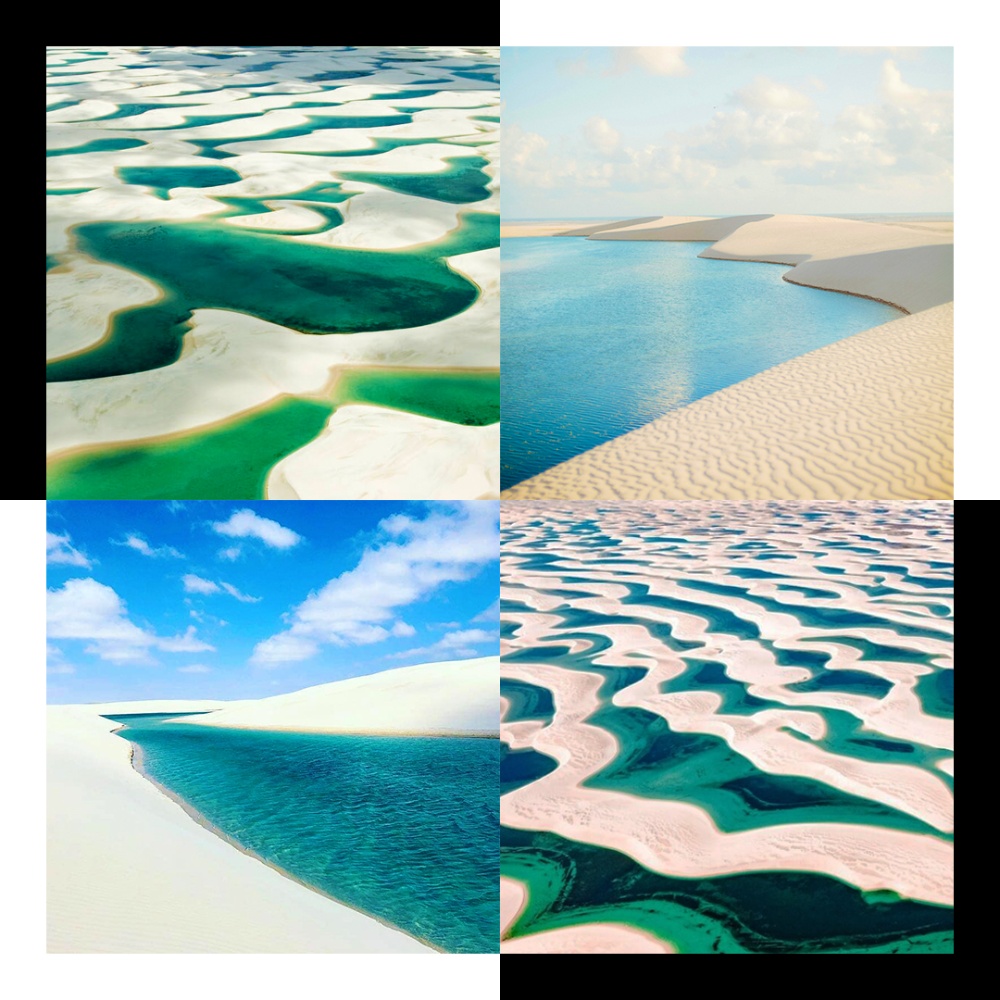

At Woodson Branch Nature School, the mission is to grow healthier communities by providing the most effective childhood education through physically engaging lessons and ample time in nature.(Photos: Courtesy Woodson Branch Nature School)

Search the scientific literature, and you’ll find paper after paper reporting on nature’s cognitive benefits. Interacting with nature improves our ability to pay attention and complete difficult mental tasks. Urban environments have the opposite effect. The nature effect is largely true across multiple studies—even with short exposures to nature or when subjects just looked at photos of wild places. Green spaces around homes and schools correlate to better cognitive development in kids and better mental function in adults. Researchers have even documented physical changes to the brain with MRI scans: One study found kids with more access to green spaces had more gray matter, which is linked to higher-level thinking and processing. Another reported that simply showing people photos of nature improved connectivity between different parts of the brain.

The evidence that nature boosts brain power is “extremely strong,” says Marc Berman, director of the Environmental Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of Chicago. “Our interaction with nature improves working memory performance and executive attention performance—those are the ones that keep replicating,” he says.

Executive attention, also known as executive functioning, simply means our ability to complete higher-level thinking. Being able to plan ahead, work toward goals, weigh complicated decisions, maintain focus, and keep control of emotions—all of these skills fall under executive function. Neuroscientists think these skills originate in the prefrontal cortex, the front part of the brain that was the last to develop, evolution-wise (and individually, too—a person’s prefrontal cortex isn’t fully developed until about age 25).

Rejuvenate Your Brain

The Stress Reduction Theory, proposed by researcher Roger Ulrich 1991, says that nature promotes relaxing physiological effects in the body, like lowered heart rate and blood pressure. And when people are less stressed, they they’re able to be more focused and creative in complex tasks. (Photos: Courtesy Woodson Branch Nature School)

Every school day, Hendrix spends his forest time in a creek, on a hill, or in the woods on Woodson Branch’s 30-acre campus. “You play in the creek–today I built a dam,” he says. “There are really good climbing trees, and you can build bridges. There’s also a big hill that’s really good for hide and seek.”

The case for nature’s benefits on the brain is so strong, Berman says, that the major research question has changed: “Now it’s about nailing down why.”

As anyone who’s spent too long staring at math problems or balance sheets knows: concentrating on something gets exhausting. Not only that, but daily life for most of us is also full of distractions—everything from an officemate’s cell phone pinging to a flashing banner ad online to email alerts piling up to a screeching garbage truck out on the street—that grab our attention, often inadvertently. Switching attention from one thing to another is also cognitively taxing, says Jason Duvall, concentration advisor and lecturer at the University of Michigan’s Program in the Environment. “We don’t really do multitasking, we do task switching,” he says. “In order to do that, we have to keep each of those things active in the brain, so it can be recalled and we can return. For every task that we add, we get worse at any other subsequent task.”

The outdoors, on the other hand, is in many ways the opposite of the busy, distraction-packed world we live in. One of the leading explanations, Attention Restoration Theory, first introduced by University of Michigan environmental psychologists Stephen and Rachel Kaplan in 1989, posits that the outdoors allows the overtaxed prefrontal cortex to rest and replenish. Attention Restoration Theory says that nature inherently brings us to a state of “soft fascination”: We find natural settings interesting and pleasurable, but they don’t require a lot of mental effort. “We think nature puts your brain into a rest state, that allows you to rejuvenate your attention resources and get back to work again,” says Berman.

Does time in nature make you smarter?

There may be other things going on, all of which could be complementing Attention Restoration Theory. Researcher Roger Ulrich proposed the Stress Reduction Theory in 1991, which says that nature promotes relaxing physiological effects in the body, like lowered heart rate and blood pressure. “When people are less stressed, they tend to be more expansive and creative in their thinking,” says Duvall.

There’s also a concept called perceptual fluency. “The idea is that elements of the natural environment tend to be easy for our visual system to process,” Duvall explains. “One explanation is that natural features have fractal patterns, or repeating patterns at different scales,” like snowflakes or tree branches. “From an information-processing perspective, the brain has an easier time making sense of what’s going on. That may explain why people feel more refreshed after those experiences—the cognitive load is lessened in natural environments.”

The why is important, but perhaps less critical than the simple fact that it just works: If a mountain of neuroscientific evidence tells us that regular nature exposure optimizes brain function, well, we should listen. Whether that means an hour of forest time at school, a daily bike ride, or a lunchtime walk around the park, getting outside is a lot more than just fun or relaxing. It’s essential.

Source

https://www.outsideonline.com/health/wellness/nature-makes-you-smarter/

https://raleighnc.gov/parks/services/nature-parks-preserves-and-programs/did-you-know-nature-can-make-your-child-smarter#:~:text=%E2%80%9CWe%20found%20strong%20evidence%20that,been%20shown%20to%20improve%20learning.%E2%80%9D

https://fullfocus.co/nature-going-outdoors/

https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_nature_makes_you_kinder_happier_more_creative

https://mayasmart.com/being-in-nature-make-kids-smarter/

https://purehealthhub.com/nature-and-the-brain-how-nature-makes-us-happier-smarter-and-kinder/