How McDonald's Earn Money?

By all appearances, McDonald's is a world famous hamburgers and fries joint. Encased within this business model, however, lies a brilliant real estate framework of long-term financing and variable operating agreements. The soul of McDonald's is its 36,000 properties, paid for with fries. McDonald’s is ubiquitous. No matter which country or major city you go to, you are bound to find a McDonald’s outlet. As of 2020, the company was operating 39,198 restaurants worldwide and held the title of ‘The World’s Largest Restaurant Company’. But what if, I told you, McDonald’s is a real estate empire hiding under the guise of a fast-food chain?

By all appearances, McDonald's is a world famous hamburgers and fries joint. Encased within this business model, however, lies a brilliant real estate framework of long-term financing and variable operating agreements. The soul of McDonald's is its 36,000 properties, paid for with fries. McDonald’s is ubiquitous. No matter which country or major city you go to, you are bound to find a McDonald’s outlet. As of 2020, the company was operating 39,198 restaurants worldwide and held the title of ‘The World’s Largest Restaurant Company’. But what if, I told you, McDonald’s is a real estate empire hiding under the guise of a fast-food chain?

In its 2020 Financial Report, the company reported 41 billion dollars worth of assets in property & equipment before accounting for depreciation, making it the 7th largest real estate company in the world even if we were to deduct the 3.5 billion dollars worth of equipment from the total $41 billion figure. McDonald’s real estate assets are the main reason behind its phenomenal and sustained success and what makes it a super interesting business case study.

So how did what seems like a restaurant come to hold 41 billion dollars of real estate, and how do these landholdings fit in the overall scheme of McDonald’s business model?

The impetus for the McDonald's real estate business model originated in the 1950's when then CFO Harry Sonneborn recognized that the real value for McDonald's would be found in its real estate, not its hamburgers. Sonneborn came up with the idea for the company to own the land and building underlying each franchise restaurant and then leasing that land and building to the franchisee. Because this freed franchisees from funding the land and property, this business model attracted more franchisees and led to the explosive growth of McDonald’s.

The McDonald's Franchise Realty Corporation was launched in 1956 with the goal of purchasing cheap property along well-traveled byways for eventual McDonald's concept franchising.

Initially, headquarters leased the land and buildings and then subleased this package to franchisees who paid as much as a 40% markup on the root lease or 5% of sales, whichever was greater. This model eventually morphed into mortgages for the properties equating to corporate ownership of both the land and building.

The franchisee's initial deposit, originally as low as $950, was used as the down payment. After setting up the franchisee to manage the business, corporate management could theoretically sit back and collect the royalty and rent checks, allowing the franchisees to purchase the property for the company.

As of Dec. 2015, McDonald's gross property, plant, and equipment totaled $37.7 billion on its balance sheet and represented just over 99% of the company's total assets.

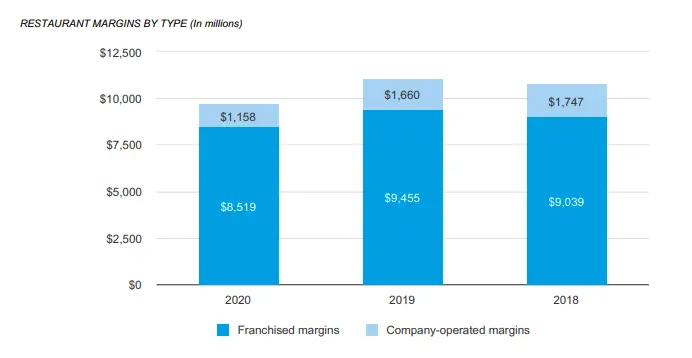

The genius of the Sonneborn financial model is that the company financed the property using long-term, fixed rates but passed along variable fees to the franchisees. As sales and prices inevitably rose over the years, the franchisee's payments to corporate as a percent of sales inflated, while the company's costs remained virtually flat. This model turned McDonald's into a cash flow powerhouse and is still the backbone of the company today. If we break up McDonald’s franchise-operated revenue further, we see that rent contributes way more to the bottom line than royalties, proving the brilliance of McDonald’s real estate model. Out of the $10.7 billion McDonald’s collected in fees from restaurants in 2020, $6.89 billion came from rent, and $3.8 billion came from franchise royalties.

If we break up McDonald’s franchise-operated revenue further, we see that rent contributes way more to the bottom line than royalties, proving the brilliance of McDonald’s real estate model. Out of the $10.7 billion McDonald’s collected in fees from restaurants in 2020, $6.89 billion came from rent, and $3.8 billion came from franchise royalties.

There was a cash flow from its leasing activities allowed McDonald’s to reinvest profits to acquire other properties. Cash flow is the ultimate arrow in the ultra-wealthy and institutional investor’s quiver for creating wealth.

Unlike traditional asset classes like stocks and bonds that rely solely on appreciation for returns on investment, cash-flowing investment properties generate consistent profits from leases that can be used to acquire more properties. You get the picture. Growth can be exponential as Sonneborn and McDonald’s proved.

Sonneborn knew that appreciation would be key to securing the company’s financial future. He was right. McDonald’s present-day real estate holdings represent $37.7 billion on its balance sheet, about 99% of all of the company’s assets.

These strong financials give McDonald’s the added benefit of negotiating the lowest loan rates and best terms available – rates and terms other borrowers only dream of – further padding the company’s pockets by lowering its borrowing costs.

Real estate appreciation is essential because even while prices fluctuate over time, in the long-run real estate values have historically always gone up – and always far ahead of inflation.

By owning the land and building, McDonald’s reaped all the tax benefits for itself. Tax benefits such as depreciation enhance the real rates of return on real estate investments, putting more money in McDonald’s pockets and boosting its bottom line.

McDonald’s reported $1.39 billion in depreciation in 2016. That’s a lot of tax savings.

Through leveraging bank financing, Sonneborn was able to expand its real estate holdings and McDonald’s operations by multiples. Conventional and unconventional real estate financing allows investors like McDonald’s to leverage their investment capital (generated from cash flow) to acquire multiple properties instead of just one, allowing for accelerated wealth creation and growth.

By diversifying its revenue stream by adding real estate across multiple geographic locations, McDonald’s shielded itself from downturns in specific markets. Revenue drops from layoffs in Pittsburgh could be absorbed by the other thousands of franchises across the world.

This model later came to known as Sonneborn Business Model.