Commodity trading strategies - Part 2

Due to storage and carry costs, the more distant months usually trade at premium to the near-month contract which means that the curve is typically in contango. That’s why contango is also known as a normal market. Though backwardation is relatively rare in commodity markets, occasionally it does occur. One of the reasons for this is short-term supply shortages of the commodity. When there is a fear that supplies may not be sufficient, traders will prefer to pay a premium to buy a commodity now rather than at some future period. We see that backwardation implies scarcity. As an investor we want to long the commodities trading in backwardation to benefit from the potential price increase.

Many research studies found out that going long commodities with backwardated term structures leads to statistically significant profits. For example, Humphreys and Shimko (1995) showed that it is possible to design a profitable strategy by trading energy futures when their curves are in backwardation. Illmanen also in his excellent book called “Expected Returns”, notes that commodities trading in backwardation (nikel, sugar, oils) have historically earned positive excess returns. Conversely, excess returns of commodities with contango term structure and negative roll yield were negative.

Some large weather events, such as frosts and droughts, can affect commodities markets through reducing the supply of a commodity. This is the reason why these commodity futures can have “weather fear premia” embedded in their prices. Investors are willing to pay a premium for these futures because of the uncertainty and magnitude of the weather event. The trading idea is that one can profit from this by shorting these overpriced commodities. Though sometimes these undesirable weather events happen and thus shorting traders will experience rare large losses, profits from the strategy are high enough to compensate for the losses.

One example of weather fear premia is coffee futures. In Brazil, the largest coffee producer in the world, the harvest season of coffee is from April through August which includes the beginning of winter season in the Southern hemisphere (note that winter begins in June in the Southern hemisphere). Coffee futures will have built-in weather risk premia in their prices because of harvest’s susceptibility to winter frosts.

Till and Eagleye (2006) look at coffee futures prices data from 1980 to 2004 and conclude that their prices did, in fact, decrease “coming into the Brazilian winter”. However, one should be careful enough to close the short position before winter begins because as mentioned above sometimes extreme weather conditions will be experienced.

Some caveats against weather risk premia built-in coffee futures. First, with Vietnam increasing its share in international coffee trade, the strategy based on Brazilian winter may lose its edge over time. Second, these strategies with their frequent small profits and infrequent large losses are not much different from shorting options. Since strategies with similar payoff profiles resulting in big losses can wipe out a portfolio, an investor should allocate only a small part of his portfolio to them.

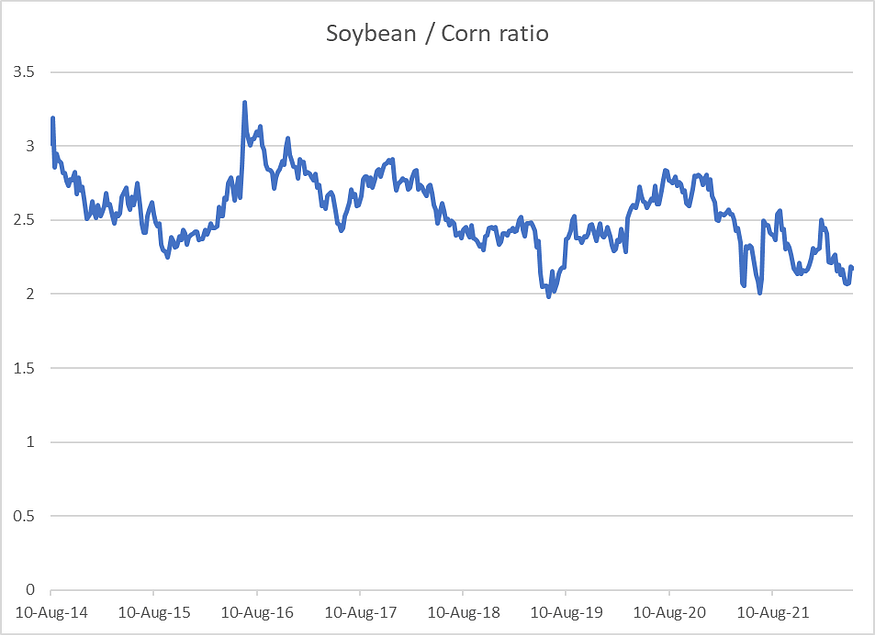

We can also design relative value trades in commodities. Alike commodities tend to be highly correlated which can be exploited profitably. For example, historically soybean traded at premium to corn with the ratio of 2.5.

Farmers will choose which crop to grow on their acreage. When the soybean to corn ratio is near or at 2, it then reverses to its historical average which means soybean appreciates more in value than corn. The pattern is not just a statistical one but follows supply-demand laws. When the ratio is high (at or near 3), it implies that soybean is more profitable than corn. That’s why farmers will plant more soybeans which will depress soybean prices. The opposite is true when the ratio is at or near 2; corn being more profitable for farmers will be followed by taking more corn than soybean to the markets which in turn will decrease corn prices.

I looked at data going back to 2014; there’s a pattern that when the soybean/corn ratio is near 2, buying soybean and selling corn was profitable. Conversely, when soybean price was three times higher than that of corn, selling soybean and buying corn offered a more attractive return. soybean / corn ration (my calculations)

soybean / corn ration (my calculations)

From the chart we can observe that in 2019 summer and 2021 summer, the ratio fell to 2 which then in both cases was followed by its reaching to historical mean of 2.5 after approximately two months.

Here is another trading opportunity related to soybean. Soybean prices tend to go down and bottom in early October. The reason why this seasonal price bottom occurs in October is that many farmers sell their crop in the harvest season.

Soybean is harvested once a year; during the remaining months the harvested crop is stored. In the US, one of largest soybean producers in the world, a big volume of soybeans is sold by farmers to generate revenue. When the supply of a commodity increases, this tends to decrease prices because supply concerns subside during this period. This causes a downward pressure on soybean prices. When this pressure abates, the market takes off. Now it should be clear why soybean tends to make its annual low in October. Given this information, how can we exploit it and build a trading strategy around it?

George Kleinman in his book “The New Commodity Trading Guide: Breakthrough Strategies for Capturing Market Profits”, looks at historical soybean futures prices data from 1968 through 2008. He compares the results of buying a July futures contract (of the following year). Out of 40 years that Kleinman’s database covers, 38 years were profitable which means that price went up from October lows. During the two unlucky years, October prices were highest for July soybean contracts.

This gives an idea for a successful trading strategy. Just buying and holding July soybean futures in October sounds too good to be true. However, by incorporating fundamental information on supply and demand (e.g, acreage, demand forecast, inventories) we can increase our odds.