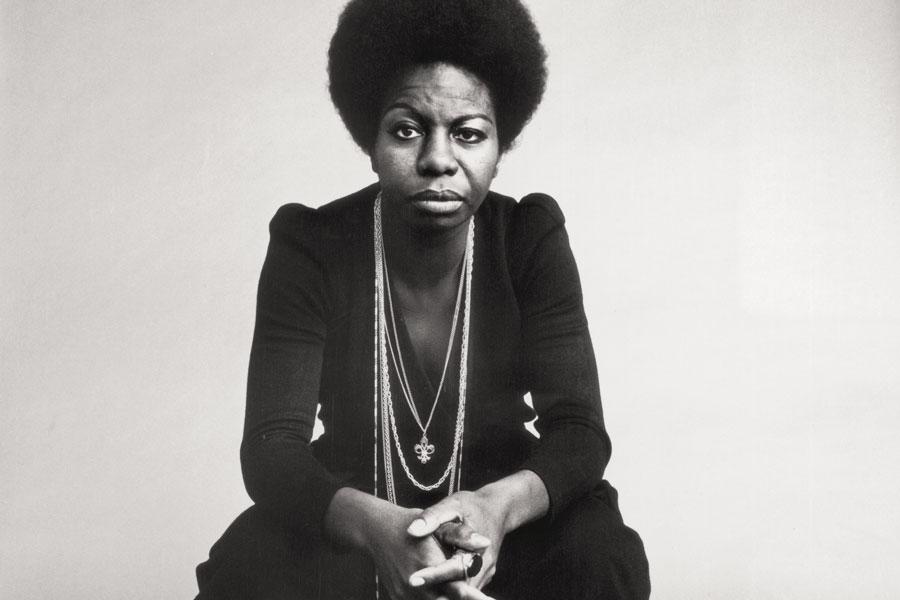

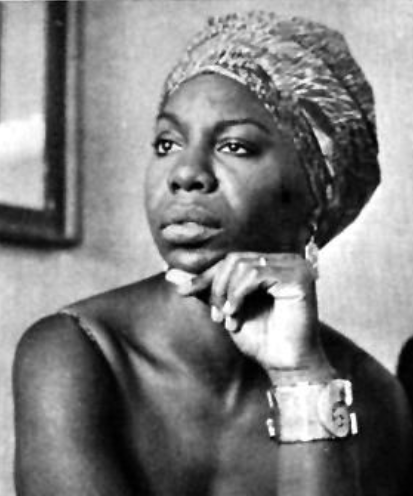

Nina Simone

Nina Simone

Simone was born on February 21, 1933, in Tryon, North Carolina. Her father, John Divine Waymon, worked as a barber and dry-cleaner as well as an entertainer, and her mother, Mary Kate Irvin, was a Methodist preacher. The sixth of eight children in a poor family, she began playing piano at the age of three or four; the first song she learned was "God Be With You, Till We Meet Again". Demonstrating a talent with the piano, she performed at her local church. Her concert debut, a classical recital, was given when she was 12. Simone later said that during this performance, her parents, who had taken seats in the front row, were forced to move to the back of the hall to make way for white people. She said that she refused to play until her parents were moved back to the front, and that the incident contributed to her later involvement in the civil rights movement. Simone's music teacher helped establish a special fund to pay for her education. Subsequently, a local fund was set up to assist her continued education. With the help of this scholarship money, she was able to attend Allen High School for Girls in Asheville, North Carolina.

After her graduation, Simone spent the summer of 1950 at the Juilliard School as a student of Carl Friedberg, preparing for an audition at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. Her application, however, was denied. Only 3 of 72 applicants were accepted that year, but as her family had relocated to Philadelphia in the expectation of her entry to Curtis, the blow to her aspirations was particularly heavy. For the rest of her life, she suspected that her application had been denied because of racial prejudice, a charge the staff at Curtis have denied. Discouraged, she took private piano lessons with Vladimir Sokoloff, a professor at Curtis, but never could re-apply. At the time, the Curtis Institute did not accept students over 21. She took a job as a photographer's assistant, found work as an accompanist at Arlene Smith's vocal studio, and taught piano from her home in Philadelphia.

To fund her private lessons, Simone performed at the Midtown Bar & Grill on Pacific Avenue in Atlantic City, New Jersey. The owner insisted that she sing as well as play the piano, which increased her income to $90 a week. In 1954, she adopted the stage name "Nina Simone". "Nina", derived from niña, was a nickname given to her by a boyfriend named Chico, and "Simone" was taken from the French actress Simone Signoret, whom she had seen in the 1952 movie Casque d'Or. Knowing her mother would not approve of playing "the Devil's music," she used her new stage name to remain undetected. Simone's mixture of jazz, blues, and classical music in her performances at the bar earned her a small but loyal fan base.

In 1958, she befriended and married Don Ross, a beatnik who worked as a fairground barker, but quickly regretted their marriage. Playing in small clubs in the same year, she recorded George Gershwin's "I Loves You, Porgy" (from Porgy and Bess), which she learned from a Billie Holiday album and performed as a favor to a friend. It became her only Billboard top 20 success in the United States, and her debut album Little Girl Blue followed in February 1959 on Bethlehem Records. Because she had sold her rights outright for $3,000, Simone lost more than $1 million in royalties (notably for the 1980s re-release of her version of the jazz standard "My Baby Just Cares for Me") and never benefited financially from the album's sales.

After the success of Little Girl Blue, Simone signed a contract with Colpix Records and recorded a multitude of studio and live albums. Colpix relinquished all creative control to her, including the choice of material that would be recorded, in exchange for her signing the contract with them. After the release of her live album Nina Simone at Town Hall, Simone became a favorite performer in Greenwich Village. By this time, Simone performed pop music only to make money to continue her classical music studies and was indifferent about having a recording contract. She kept this attitude toward the record industry for most of her career.

Simone married Andrew Stroud, a detective with the New York Police Department, in December 1961. In a few years, he became her manager and the father of her daughter Lisa, but later he abused Simone psychologically and physically.

In 1964, Simone changed record distributors from Colpix, an American company, to the Dutch Philips Records, which meant a change in the content of her recordings. She had always included songs in her repertoire that drew on her African-American heritage, such as "Brown Baby" by Oscar Brown and "Zungo" by Michael Olatunji on her album Nina at the Village Gate in 1962. On her debut album for Philips, Nina Simone in Concert (1964), for the first time, she addressed racial inequality in the United States in the song "Mississippi Goddam". This was her response to the June 12, 1963, murder of Medgar Evers and the September 15, 1963, bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed four young black girls and partly blinded a fifth.

She said that the song was "like throwing ten bullets back at them," becoming one of many other protest songs written by Simone. The song was released as a single, and it was boycotted in some southern states. Promotional copies were smashed by a Carolina radio station and returned to Philips. She later recalled how "Mississippi Goddam" was her "first civil rights song" and that the song came to her "in a rush of fury, hatred and determination". The song challenged the belief that race relations could change gradually and called for more immediate developments: "me and my people are just about due." It was a key moment in her path to Civil Rights activism. "Old Jim Crow," on the same album, addressed the Jim Crow laws. After "Mississippi Goddam," a civil rights message was the norm in Simone's recordings and became part of her concerts. As her political activism rose, the rate of release of her music slowed.

Simone performed and spoke at civil rights meetings, including at the Selma to Montgomery marches. Like Malcolm X, her neighbor in Mount Vernon, New York, she supported black nationalism and advocated violent revolution rather than Martin Luther King Jr.'s non-violent approach. She hoped that African Americans could use armed combat to form a separate state, though she wrote in her autobiography that she and her family regarded all races as equal.

In 1967, Simone moved from Philips to RCA Victor. She sang "Backlash Blues" written by her friend, Harlem Renaissance leader Langston Hughes, on her first RCA album, Nina Simone Sings the Blues (1967). On Silk & Soul (1967), she recorded Billy Taylor's "I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free" and "Turning Point". The album 'Nuff Said! (1968) contained live recordings from the Westbury Music Fair of April 7, 1968, three days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. She dedicated the performance to him and sang "Why? (The King of Love Is Dead)," a song written by her bass player, Gene Taylor. In 1969, she performed at the Harlem Cultural Festival in Harlem's Mount Morris Park. The performance was recorded and is featured in Questlove's 2021 documentary Summer of Soul.

Simone and Weldon Irvine turned the unfinished play To Be Young, Gifted and Black by Lorraine Hansberry into a civil rights song of the same name. She credited her friend Hansberry with cultivating her social and political consciousness. She performed the song live on the album Black Gold (1970). A studio recording was released as a single, and renditions of the song have been recorded by Aretha Franklin (on her 1972 album Young, Gifted and Black) and Donny Hathaway. When reflecting on this period, she wrote in her autobiography, "I felt more alive then than I feel now because I was needed, and I could sing something to help my people."

In an interview for Jet magazine, Simone stated that her controversial song "Mississippi Goddam" harmed her career. She claimed that the music industry punished her by boycotting her records. Hurt and disappointed, Simone left the US in September 1970, flying to Barbados and expecting her husband and manager Stroud to communicate with her when she had to perform again. However, Stroud interpreted Simone's sudden disappearance, and the fact that she had left behind her wedding ring, as an indication of her desire for a divorce. As her manager, Stroud was in charge of Simone's income.

When Simone returned to the United States, she learned that a warrant had been issued for her arrest for unpaid taxes (allegedly unpaid as a protest against her country's involvement with the Vietnam War) and fled to Barbados to evade the authorities and prosecution. Simone stayed in Barbados for quite some time and had a lengthy affair with the Prime Minister, Errol Barrow. A close friend, singer Miriam Makeba, then persuaded her to go to Liberia.

When Simone relocated, she abandoned her daughter Lisa in Mount Vernon. Lisa eventually reunited with Simone in Liberia, but, according to Lisa, her mother was physically and mentally abusive. The abuse was so unbearable that Lisa became suicidal, and she moved back to New York to live with her father Andrew Stroud. Simone recorded her last album for RCA, It Is Finished, in 1974, and did not make another record until 1978 when she was persuaded to go into the recording studio by CTI Records owner Creed Taylor. The result was the album Baltimore, which, while not a commercial success, was fairly well received critically and marked a quiet artistic renaissance in Simone's recording output. Her choice of material retained its eclecticism, ranging from spiritual songs to Hall & Oates' "Rich Girl". Four years later, Simone recorded Fodder on My Wings on a French label, Studio Davout.

During the 1980s, Simone performed regularly at Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club in London, where she recorded the album Live at Ronnie Scott's in 1984. Although her early on-stage style could be somewhat haughty and aloof, in later years, Simone particularly seemed to enjoy engaging with her audiences sometimes, by recounting humorous anecdotes related to her career and music and by soliciting requests. By this time, she lived in Liberia, Barbados, Switzerland, and eventually ended up in Paris. There she regularly performed in a small jazz club called Aux Trois Mailletz for relatively small financial reward. The performances were sometimes brilliant, and at other times, Nina Simone gave up after fifteen minutes. Often she was too drunk to sing or play the piano properly. At other times, she scolded the audience, so that manager Raymond Gonzalez, guitarist Al Schackman, and Gerrit de Bruin, a Dutch friend of hers, decided to intervene.:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2):format(webp)/Zoe-Saldana-Nina-Simone-58ade8d376ae43e4a0610be1d175b3e0.jpg)

In 1987, Simone scored a huge European hit with the song "My Baby Just Cares for Me". Recorded by her for the first time in 1958, the song was used in a commercial for Chanel No. 5 perfume in Europe, leading to a re-release of the recording. This stormed to number 4 on the UK's NME singles chart, giving Simone a brief surge in popularity in the UK and elsewhere.

In the spring of 1988, Simone moved to Nijmegen in the Netherlands. She bought an apartment next to the Belvoir Hotel with views of the Waalbrug and Ooijpolder, with the help of her friend Gerrit de Bruin, who lived with his family a few corners away and kept an eye on her. The idea was to bring Simone to Nijmegen to relax and get back on track. A daily caretaker, Jackie Hammond from London, was hired for her. She was known for her temper and outbursts of aggression. Unfortunately, the tantrums followed her to Nijmegen. Simone was diagnosed with bipolar disorder by a friend of De Bruin, who prescribed Trilafon for her. Despite the illness, it was generally a happy time for Simone in Nijmegen, where she could lead a fairly anonymous life. Only a few recognized her; most Nijmegen people did not know who she was. Slowly but surely her life started to improve, and she was even able to make money from the Chanel commercial after a legal battle. In 1991, Nina Simone exchanged Nijmegen for Amsterdam, where she lived for two years with friends and Hammond.

In 1993, Simone settled near Aix-en-Provence in southern France (Bouches-du-Rhône). In the same year, her final album, A Single Woman, was released. She variously contended that she married or had a love affair with a Tunisian around this time, but that their relationship ended because, "His family didn't want him to move to France, and France didn't want him because he's a North African." During a 1998 performance in Newark, she announced, "If you're going to come see me again, you've got to come to France because I am not coming back." She suffered from breast cancer for several years before she died in her sleep at her home in Carry-le-Rouet (Bouches-du-Rhône) on April 21, 2003.

Her Catholic funeral service at the local parish was attended by singers Miriam Makeba and Patti LaBelle, poet Sonia Sanchez, actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, and hundreds of others. Simone's ashes were scattered in several African countries. Her daughter Lisa Celeste Stroud is an actress and singer who took the stage name Simone, and who has appeared on Broadway in Aida.

Simone's consciousness on racial and social discourse was prompted by her friendship with the playwright Lorraine Hansberry. Simone stated that during her conversations with Hansberry, "we never talked about men or clothes. It was always Marx, Lenin, and revolution – real girls' talk." The influence of Hansberry planted the seed for the provocative social commentary that became an expectation in Simone's repertoire. One of Nina's more hopeful activism anthems, "To Be Young, Gifted and Black," was written with collaborator Weldon Irvine in the years following the playwright's passing, acquiring the title of one of Hansberry's unpublished plays.

Simone's social circles included notable black activists such as James Baldwin, Stokely Carmichael, and Langston Hughes; the lyrics of her song "Backlash Blues" were written by Hughes.

Simone's social commentary was not limited to the civil rights movement; the song "Four Women" exposed the Eurocentric appearance standards imposed on Black women in America, as it explored the internalized dilemma of beauty experienced by four Black women with skin tones ranging from light to dark. She explained in her autobiography, I Put a Spell on You, that the purpose of the song was to inspire Black women to define beauty and identity for themselves without the influence of societal impositions. Chardine Taylor-Stone has noted that, beyond the politics of beauty, the song also describes the stereotypical roles that many Black women have historically been restricted to: the mammy, the tragic mulatto, the sex worker, and the angry Black woman.

Throughout her career, Simone assembled a collection of songs that became standards in her repertoire. Some were songs that she wrote herself, while others were new arrangements of other standards, and others had been written especially for the singer. Her first hit song in America was her rendition of George Gershwin's "I Loves You, Porgy" (1958), which peaked at number 18 on the Billboard magazine Hot 100 chart.

During that same period, Simone recorded "My Baby Just Cares for Me," which would become her biggest success years later, in 1987, after it was featured in a 1986 Chanel No. 5 perfume commercial. Well-known songs from her Philips albums include "Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood" on Broadway-Blues-Ballads (1964); "I Put a Spell on You", "Ne me quitte pas" (a rendition of a Jacques Brel song), and "Feeling Good" on I Put a Spell On You (1965); and "Lilac Wine" and "Wild Is the Wind" on Wild is the Wind (1966).

"Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood" and her takes on "Sinnerman" (Pastel Blues, 1965) and "Feeling Good" have remained popular in cover versions, sample usage, and their use on soundtracks for various movies, television series, and video games. "Sinnerman" has been featured in multiple films and TV series, and the song "Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood" was sampled by various artists. "See-Line Woman" was sampled by Kanye West for "Bad News" on his album 808s & Heartbreak. The 1965 rendition of "Strange Fruit," originally recorded by Billie Holiday, was sampled by Kanye West for "Blood on the Leaves" on his album Yeezus.

Simone's years at RCA spawned many singles and album tracks that were popular, particularly in Europe. In 1968, "Ain't Got No, I Got Life," a medley from the musical Hair from the album 'Nuff Said! (1968), became a surprise hit for Simone, reaching number 2 on the UK Singles Chart. In 2006, it returned to the UK Top 30 in a remixed version by Groovefinder.

The following single, a rendition of the Bee Gees' "To Love Somebody," also reached the UK Top 10 in 1969. "The House of the Rising Sun" was featured on Nina Simone Sings the Blues in 1967, but Simone had recorded the song in 1961, and it was featured on Nina at the Village Gate (1962).

Simone's bearing and stage presence earned her the title "the High Priestess of Soul". She was a pianist, singer, and performer, displaying these talents both separately and simultaneously. As a composer and arranger, Simone traversed genres from gospel to blues, jazz, and folk, incorporating elements of European classical styling. In addition to using Bach-style counterpoint, she drew inspiration from the virtuosity of 19th-century Romantic piano repertoire, including Chopin, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, and others. Jazz trumpeter Miles Davis spoke highly of Simone, impressed by her ability to play three-part counterpoint and seamlessly integrate it into pop songs and improvisation.

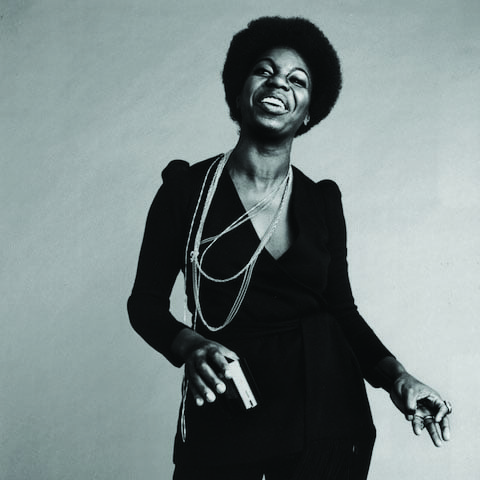

Onstage, Simone integrated monologues and dialogues with the audience into her performances and often employed silence as a musical element. Throughout most of her life and recording career, she was accompanied by percussionist Leopoldo Fleming and guitarist/musical director Al Schackman. Known for her attention to venue design and acoustics, she tailored her performances to individual locations. Rolling Stone once remarked that Simone could "channel every facet of lived experience." She was often credited for expressing an expansive emotional range in her music, ranging from immeasurable rage to limitless joy.

Simone was perceived as a sometimes difficult or unpredictable performer, occasionally admonishing the audience if she felt they were disrespectful. Schackman would try to calm Simone during these episodes, performing solo until she calmed offstage and returned to finish the engagement. Simone's early experiences as a classical pianist conditioned her to expect quiet and attentive audiences, and her frustration tended to surface in nightclubs, lounges, or other venues where patrons were less attentive. Schackman described her live appearances as hit or miss, either reaching heights of hypnotic brilliance or, on the other hand, mechanically playing a few songs and then abruptly ending concerts early.

Simone is widely regarded as one of the most influential recording artists in 20th-century jazz, cabaret, and R&B genres. According to Rickey Vincent, she was a pioneering musician characterized by "fits of outrage and improvisational genius." Simone's composition of "Mississippi Goddam" was seen as groundbreaking, showcasing her courage as "an established black musical entertainer to break from the norms of the industry and produce direct social commentary in her music during the early 1960s."

Rolling Stone noted that "her honey-coated, slightly adenoidal cry was one of the most affecting voices of the civil rights movement," highlighting her ability to "belt barroom blues, croon cabaret, and explore jazz—sometimes all on a single record." AllMusic's Mark Deming described her as "one of the most gifted vocalists of her generation, and also one of the most eclectic." Creed Taylor, in the liner notes for Simone's 1978 Baltimore album, praised her "magnificent intensity" that could turn even the simplest phrase into a radiant, poetic message. Jim Fusilli, a music critic for The Wall Street Journal, emphasized that Simone's music remains relevant today, with her vocal delivery, piano skills, and emotional performances still dazzling.

Maya Angelou wrote in 1970, "She is loved or feared, adored or disliked, but few who have met her music or glimpsed her soul react with moderation." However, Robert Christgau, who held a negative view of Simone, criticized her penchant for the mundane and described her intensity as bogus. He dismissed her piano playing as that of a "middlebrow keyboard tickler" and attributed his overall negative appraisal to Simone's consistent seriousness of manner, depressive tendencies, and classical background.

Simone was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in the late 1980s. Known for her temper and outbursts of aggression, she exhibited challenging behavior throughout her life. In 1985, Simone fired a gun at a record company executive, whom she accused of stealing royalties. While she admitted to trying to harm him, she claimed she missed. In 1995, while living in France, she shot and wounded her neighbor's son with an air gun after being disturbed by the boy's laughter. She perceived his response to her complaints as racial insults. Simone was sentenced to eight months in jail, a term that was suspended pending a psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

According to a biographer, Simone began taking medication in the mid-1960s, a fact known only to a small group of intimates. After her death, it was revealed that the medication was the anti-psychotic Trilafon. Simone's friends and caretakers sometimes mixed the medication into her food surreptitiously when she refused to follow her treatment plan. This information remained private until 2004 when a posthumous biography titled "Break Down and Let It All Out," written by Sylvia Hampton and David Nathan, was published. Singer-songwriter Janis Ian, a one-time friend of Simone's, recounted instances in her autobiography, including an incident where Simone forced a shoe store cashier at gunpoint to take back a pair of sandals she had already worn and another where Simone demanded a royalty payment from Ian, ripping a pay telephone out of its wall when refused.

References

- Nina Simone in the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary^ Jump up to:

- a b Simone & Cleary 2003, pp. 1–62

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Jazz Musicians – Nina Simone (Eunice Kathleen Waymon)". Jazz.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2013.^ Jump up to:

- a b c d Liz Garbus, 2015 documentary film, What Happened, Miss Simone?^ Jump up to:

- a b "The Nina Simone Foundation". Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- ^ Pierpont, Claudia Roth (August 6, 2014). "A Raised Voice: How Nina Simone turned the movement into music". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on August 6, 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ Simone & Cleary 2003, p. 23.

- ^ Simone & Cleary 2003, p. 91.