WATER FOR LIFE !

The Indians of the Andes call it Camanchaca, the wetting fog. When the cold air rising from the icy Humboldt current collides with the warm air over the sunbaked Chilean coast, it forms a thick, white ribbon of mist that hugs the high ridge above Chungungo, 600 kilometers north of Santiago. But the Camanchaca clouds never burst into rain - by afternoon, the sun burns them away and the landscape remains arid as any desert. The lack of rainfall made agriculture almost impossible, and even basic needs like drinking water and sanitation became luxuries. A shower was a rare luxury, and vegetables came from the market 80 kilometers away.

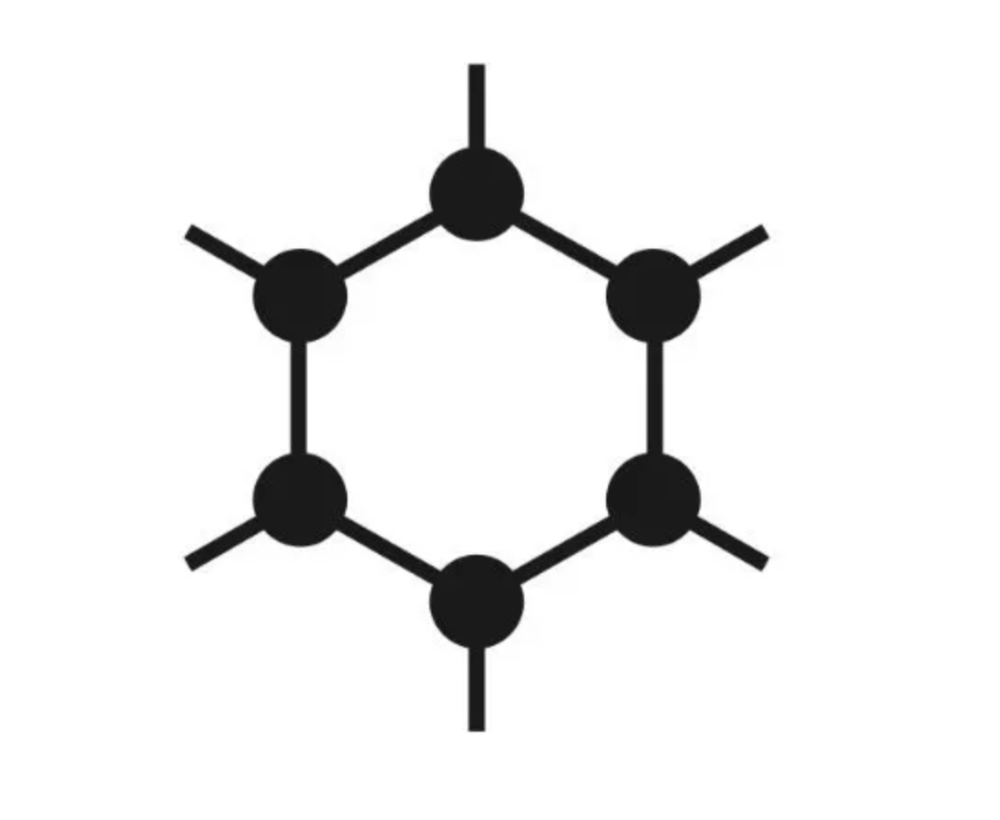

But fortunes have changed for Chungungo's 320 residents. It was no sudden climatic shift – the village still receives only about 40 centimeters of rain a year – but rather the adaptation of traditional technologies to harvest the Camanchaca. High on the ridge overlooking the town, near the abandoned El Tofo iron mine, several dozen pairs of wooden posts have been planted in the ground. Strung between them are giant nets made of fine polypropylene. Like great spider webs, these nets capture the fog, trapping pearls of water in the fine mesh. The droplets slowly trickle down the mesh into a plastic trough, and gravity does the rest. The troughs drain into rubber tubing, which transports the water through a series of small tanks and filters and finally to a 25,000-gallon storage tank 2,000 feet below, where it is treated with chlorine to kill germs. On a good day, the 'fog harvest' supplies 2,500 gallons of fresh water - all the water Chungungo can drink plus some for bathing and gardening. Flower and vegetable gardens have appeared in patches that were once only dust and gravel. Now, the residents wash clothes every day, grow their vegetables and take a bath any time they want.

Reaping the fog is hardly new. For centuries, the Quechua placed bowls below tree trunks to harvest fog water, and there is evidence that the practice dates back thousands of years. In the 1960s, Chilean scientists began to research ways to use the fog to help restore forests that had been levelled to stoke the wood-burning furnaces of iron mines like El Tofo. "But we never imagined supplying drinking water," said Waldo Canto Veras, director of the Chilean Forestry Agency, Conaf. With a $150,000 grant and technical help from Canada, Conaf succeeded in reaping the fog. The water is not only clean but half as expensive as hauling water over the mountain by truck, the only way to supply the village since an electrical train line that served the iron mine shut down when the mine closed in the 1960s.

This project has shown them that there are cheap, practical, environmentally friendly ways to bring water to poor communities. That message is resonating worldwide. Some 47 coastal locations in 30 countries have conditions similar to Chungungo's. Officials in Asia, Africa and other regions of Latin America have visited the town, which can supply a population of about 1,000, and begun research into their own coastal fog systems. In Chungungo, the ready supply of water has brought not only new uses like gardening and icemaking but also newcomers, increasing the strain on the new system. But that seems a small price to a people whose hopes, like their lands, dried up long ago.