International Monetary Fund

"IMF" redirects here. For other uses, see IMF (disambiguation).

International Monetary Fund

Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

AbbreviationIMFFormation27 December 1945; 78 years agoTypeInternational financial institutionPurposePromote international monetary co-operation, facilitate international trade, foster sustainable economic growth, make resources available to members experiencing balance of payments difficulties, prevent and assist with recovery from international financial crises[1]Headquarters700 19th Street NW, Washington, D.C., U.S.Coordinates 38°53′56″N 77°2′39″WRegionWorldwideMembership190 countries (189 UN countries and Kosovo)[2]Official languageEnglish[3]Managing DirectorKristalina GeorgievaFirst Deputy Managing DirectorGita Gopinath[4]Chief EconomistPierre-Olivier Gourinchas[5]Main organBoard of GovernorsParent organization

38°53′56″N 77°2′39″WRegionWorldwideMembership190 countries (189 UN countries and Kosovo)[2]Official languageEnglish[3]Managing DirectorKristalina GeorgievaFirst Deputy Managing DirectorGita Gopinath[4]Chief EconomistPierre-Olivier Gourinchas[5]Main organBoard of GovernorsParent organization Budget (2022)$1.2 billion USD[8]Staff2,400[1]Website

Budget (2022)$1.2 billion USD[8]Staff2,400[1]Website

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 190 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of last resort to national governments, and a leading supporter of exchange-rate stability. Its stated mission is "working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world."[1][9] Established on December 27, 1945[10] at the Bretton Woods Conference, primarily according to the ideas of Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, it started with 29 member countries and the goal of reconstructing the international monetary system after World War II. It now plays a central role in the management of balance of payments difficulties and international financial crises.[11] Through a quota system, countries contribute funds to a pool from which countries can borrow if they experience balance of payments problems. As of 2016, the fund had SDR 477 billion (about US$667 billion).[10]

The IMF works to stabilize and foster the economies of its member countries by its use of the fund, as well as other activities such as gathering and analyzing economic statistics and surveillance of its members' economies.[12][13] IMF funds come from two major sources: quotas and loans. Quotas, which are pooled funds from member nations, generate most IMF funds. The size of members' quotas increase according to their economic and financial importance in the world. The quotas are increased periodically as a means of boosting the IMF's resources in the form of special drawing rights.[14]

The current managing director (MD) and chairwoman of the IMF is Bulgarian economist Kristalina Georgieva, who has held the post since October 1, 2019.[15] Indian-American economist Gita Gopinath, previously the chief economist, was appointed as first deputy managing director, effective January 21, 2022.[16] Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas was appointed chief economist on January 24, 2022.[17]

Functions

Board of Governors International Monetary Fund (1999)

Board of Governors International Monetary Fund (1999)

According to the IMF itself, it works to foster global growth and economic stability by providing policy advice and financing the members by working with developing countries to help them achieve macroeconomic stability and reduce poverty.[18] The rationale for this is that private international capital markets function imperfectly and many countries have limited access to financial markets. Such market imperfections, together with balance-of-payments financing, provide the justification for official financing, without which many countries could only correct large external payment imbalances through measures with adverse economic consequences.[19] The IMF provides alternate sources of financing such as the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility.[20]

Upon the founding of the IMF, its three primary functions were:

- to oversee the fixed exchange rate arrangements between countries,[21] thus helping national governments manage their exchange rates and allowing these governments to prioritize economic growth,[22] and

- to provide short-term capital to aid the balance of payments[21] and prevent the spread of international economic crises.

- to help mend the pieces of the international economy after the Great Depression and World War II[23] as well as to provide capital investments for economic growth and projects such as infrastructure.[citation needed]

The IMF's role was fundamentally altered by the floating exchange rates after 1971. It shifted to examining the economic policies of countries with IMF loan agreements to determine whether a shortage of capital was due to economic fluctuations or economic policy. The IMF also researched what types of government policy would ensure economic recovery.[21] A particular concern of the IMF was to prevent financial crises, such as those in Mexico in 1982, Brazil in 1987, East Asia in 1997–98, and Russia in 1998, from spreading and threatening the entire global financial and currency system. The challenge was to promote and implement a policy that reduced the frequency of crises among emerging market countries, especially the middle-income countries which are vulnerable to massive capital outflows.[24] Rather than maintaining a position of oversight of only exchange rates, their function became one of surveillance of the overall macroeconomic performance of member countries. Their role became a lot more active because the IMF now manages economic policy rather than just exchange rates.[citation needed]

In addition, the IMF negotiates conditions on lending and loans under their policy of conditionality,[21] which was established in the 1950s.[22] Low-income countries can borrow on concessional terms, which means there is a period of time with no interest rates, through the Extended Credit Facility (ECF), the Standby Credit Facility (SCF) and the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF). Non-concessional loans, which include interest rates, are provided mainly through the Stand-By Arrangements (SBA), the Flexible Credit Line (FCL), the Precautionary and Liquidity Line (PLL), and the Extended Fund Facility. The IMF provides emergency assistance via the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) to members facing urgent balance-of-payments needs.[25]

Surveillance of the global economy

The IMF is mandated to oversee the international monetary and financial system and monitor the economic and financial policies of its member countries.[26] This activity is known as surveillance and facilitates international co-operation.[27] Since the demise of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in the early 1970s, surveillance has evolved largely by way of changes in procedures rather than through the adoption of new obligations.[26] The responsibilities changed from those of guardians to those of overseers of members' policies.[citation needed]

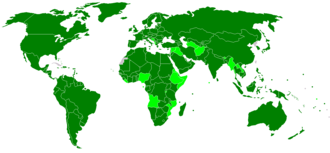

The Fund typically analyses the appropriateness of each member country's economic and financial policies for achieving orderly economic growth, and assesses the consequences of these policies for other countries and for the global economy.[26] For instance, The IMF played a significant role in individual countries, such as Armenia and Belarus, in providing financial support to achieve stabilization financing from 2009 to 2019.[28] The maximum sustainable debt level of a polity, which is watched closely by the IMF, was defined in 2011 by IMF economists to be 120%.[29] Indeed, it was at this number that the Greek economy melted down in 2010.[30] IMF Data Dissemination Systems participants:

IMF Data Dissemination Systems participants:

IMF member using SDDS

IMF member using GDDS

IMF member, not using any of the DDSystems

non-IMF entity using SDDS

non-IMF entity using GDDS

no interaction with the IMF

In 1995, the International Monetary Fund began to work on data dissemination standards with the view of guiding IMF member countries to disseminate their economic and financial data to the public. The International Monetary and Financial Committee (IMFC) endorsed the guidelines for the dissemination standards and they were split into two tiers: The General Data Dissemination System (GDDS) and the Special Data Dissemination Standard (SDDS).[31]

The executive board approved the SDDS and GDDS in 1996 and 1997, respectively, and subsequent amendments were published in a revised Guide to the General Data Dissemination System. The system is aimed primarily at statisticians and aims to improve many aspects of statistical systems in a country. It is also part of the World Bank Millennium Development Goals (MDG) and Poverty Reduction Strategic Papers (PRSPs).[citation needed]

The primary objective of the GDDS is to encourage member countries to build a framework to improve data quality and statistical capacity building to evaluate statistical needs, set priorities in improving timeliness, transparency, reliability, and accessibility of financial and economic data. Some countries initially used the GDDS, but later upgraded to SDDS.[citation needed]

Some entities that are not IMF members also contribute statistical data to the systems:

- Palestinian Authority – GDDS

- Hong Kong – SDDS

- Macau – GDDS[32]

- Institutions of the European Union:

- The European Central Bank for the Eurozone – SDDS

- Eurostat for the whole EU – SDDS, thus providing data from Cyprus (not using any DDSystem on its own) and Malta (using only GDDS on its own)[citation needed]

A 2021 study found that the IMF's surveillance activities have "a substantial impact on sovereign debt with much greater impacts in emerging than high-income economies".[33]

World Economic Outlook

World Economic Outlook is a survey, published twice a year, by International Monetary Fund staff, which analyzes the global economy in the near and medium term.[34]

Conditionality of loans

IMF conditionality is a set of policies or conditions that the IMF requires in exchange for financial resources.[21] The IMF does require collateral from countries for loans but also requires the government seeking assistance to correct its macroeconomic imbalances in the form of policy reform.[35] If the conditions are not met, the funds are withheld.[21][36] The concept of conditionality was introduced in a 1952 executive board decision and later incorporated into the Articles of Agreement.

Conditionality is associated with economic theory as well as an enforcement mechanism for repayment. Stemming primarily from the work of Jacques Polak, the theoretical underpinning of conditionality was the "monetary approach to the balance of payments".[22]

Structural adjustment

Further information: Structural adjustment

Some of the conditions for structural adjustment can include:

- Cutting expenditures or raising revenues, also known as austerity.

- Focusing economic output on direct export and resource extraction,

- Devaluation of currencies,

- Trade liberalisation, or lifting import and export restrictions,

- Increasing the stability of investment (by supplementing foreign direct investment with the opening of facilities for the domestic market),

- Balancing budgets and not overspending,

- Removing price controls and state subsidies,

- Privatization, or divestiture of all or part of state-owned enterprises,

- Enhancing the rights of foreign investors vis-a-vis national laws,

- Improving governance and fighting corruption,

These conditions are known as the Washington Consensus.

Benefits

These loan conditions ensure that the borrowing country will be able to repay the IMF and that the country will not attempt to solve their balance-of-payment problems in a way that would negatively impact the international economy.[37][38] The incentive problem of moral hazard—when economic agents maximise their own utility to the detriment of others because they do not bear the full consequences of their actions—is mitigated through conditions rather than providing collateral; countries in need of IMF loans do not generally possess internationally valuable collateral anyway.[38]

Conditionality also reassures the IMF that the funds lent to them will be used for the purposes defined by the Articles of Agreement and provides safeguards that the country will be able to rectify its macroeconomic and structural imbalances.[38] In the judgment of the IMF, the adoption by the member of certain corrective measures or policies will allow it to repay the IMF, thereby ensuring that the resources will be available to support other members.[36]

As of 2004, borrowing countries have had a good track record for repaying credit extended under the IMF's regular lending facilities with full interest over the duration of the loan. This indicates that IMF lending does not impose a burden on creditor countries, as lending countries receive market-rate interest on most of their quota subscription, plus any of their own-currency subscriptions that are loaned out by the IMF, plus all of the reserve assets that they provide the IMF.[19]

History

Plaque Commemorating the Formation of the IMF in July 1944 at the Bretton Woods Conference

Plaque Commemorating the Formation of the IMF in July 1944 at the Bretton Woods Conference IMF "Headquarters 1" in Washington, D.C., designed by Moshe Safdie

IMF "Headquarters 1" in Washington, D.C., designed by Moshe Safdie The Gold Room within the Mount Washington Hotel, where the Bretton Woods Conference attendees signed the agreements creating the IMF and World Bank

The Gold Room within the Mount Washington Hotel, where the Bretton Woods Conference attendees signed the agreements creating the IMF and World Bank First page of the Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund, 1 March 1946. Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs archives.

First page of the Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund, 1 March 1946. Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs archives.

The IMF was originally laid out as a part of the Bretton Woods system exchange agreement in 1944.[39] During the Great Depression, countries sharply raised barriers to trade in an attempt to improve their failing economies. This led to the devaluation of national currencies and a decline in world trade.[40]

This breakdown in international monetary cooperation created a need for oversight. The representatives of 45 governments met at the Bretton Woods Conference in the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in the United States, to discuss a framework for postwar international economic cooperation and how to rebuild Europe.

There were two views on the role the IMF should assume as a global economic institution. American delegate Harry Dexter White foresaw an IMF that functioned more like a bank, making sure that borrowing states could repay their debts on time.[41] Most of White's plan was incorporated into the final acts adopted at Bretton Woods. British economist John Maynard Keynes, on the other hand, imagined that the IMF would be a cooperative fund upon which member states could draw to maintain economic activity and employment through periodic crises. This view suggested an IMF that helped governments and act as the United States government had during the New Deal to the great depression of the 1930s.[41]

The IMF formally came into existence on 27 December 1945, when the first 29 countries ratified its Articles of Agreement.[42] By the end of 1946 the IMF had grown to 39 members.[43] On 1 March 1947, the IMF began its financial operations,[44] and on 8 May France became the first country to borrow from it.[43]

The IMF was one of the key organizations of the international economic system; its design allowed the system to balance the rebuilding of international capitalism with the maximization of national economic sovereignty and human welfare, also known as embedded liberalism.[22] The IMF's influence in the global economy steadily increased as it accumulated more members. Its membership began to expand in the late 1950s and during the 1960s as many African countries became independent and applied for membership. But the Cold War limited the Fund's membership, with most countries in the Soviet sphere of influence not joining until 1970s and 1980s.[40][45][46]

The Bretton Woods exchange rate system prevailed until 1971 when the United States government suspended the convertibility of the US$ (and dollar reserves held by other governments) into gold. This is known as the Nixon Shock.[40] The changes to the IMF articles of agreement reflecting these changes were ratified in 1976 by the Jamaica Accords. Later in the 1970s, large commercial banks began lending to states because they were awash in cash deposited by oil exporters. The lending of the so-called money center banks led to the IMF changing its role in the 1980s after a world recession provoked a crisis that brought the IMF back into global financial governance.[47]

In the mid-1980s, the IMF shifted its narrow focus from currency stabilization to a broader focus of promoting market-liberalizing reforms through structural adjustment programs.[48] This shift occurred without a formal renegotiation of the organization's charter or operational guidelines.[48] The Ronald Reagan administration, in particular Treasury Secretary James Baker, his assistant secretary David Mulford and deputy assistant secretary Charles Dallara, pressured the IMF to attach market-liberal reforms to the organization's conditional loans.[48]

During the 20th century, the IMF shifted its position on capital controls. Whereas the IMF permitted capital controls at its founding and throughout the 1970s, IMF staff increasingly favored free capital movement from 1980s onwards.[49] This shift happened in the aftermath of an emerging consensus in economics on the desirability of free capital movement, retirement of IMF staff hired in the 1940s and 1950s, and the recruitment of staff exposed to new thinking in economics.[49]

Response and analysis of coronavirus

In late 2019, the IMF estimated global growth in 2020 to reach 3.4%, but due to the coronavirus, in November 2020, it expected the global economy to shrink by 4.4%.[69][70]

In March 2020, Kristalina Georgieva announced that the IMF stood ready to mobilize $1 trillion as its response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[71] This was in addition to the $50 billion fund it had announced two weeks earlier,[72] of which $5 billion had already been requested by Iran.[73] One day earlier on 11 March, the UK called to pledge £150 million to the IMF catastrophe relief fund.[74] It came to light on 27 March that "more than 80 poor and middle-income countries" had sought a bailout due to the coronavirus.[75]

On 13 April 2020, the IMF said that it "would provide immediate debt relief to 25 member countries under its Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT)" programme.[76]

Member countries

IMF member states

IMF member states

IMF member states not accepting the obligations of Article VIII, Sections 2, 3, and 4[77]

Former IMF states/non-participants/no data available

Not all member countries of the IMF are sovereign states, and therefore not all "member countries" of the IMF are members of the United Nations.[78] Amidst "member countries" of the IMF that are not member states of the UN are non-sovereign areas with special jurisdictions that are officially under the sovereignty of full UN member states, such as Aruba, Curaçao, Hong Kong, and Macao, as well as Kosovo.[79][80] The corporate members appoint ex-officio voting members, who are listed below. All members of the IMF are also International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) members and vice versa.[81]

Former members are Cuba (which left in 1964),[82] and Taiwan, which was ejected from the IMF[83] in 1980 after losing the support of the then United States President Jimmy Carter and was replaced by the People's Republic of China.[84] However, "Taiwan Province of China" is still listed in the official IMF indices.[85]

Apart from Cuba, the other UN states that do not belong to the IMF are Liechtenstein, Monaco and North Korea. However, Andorra became the 190th member on 16 October 2020.[86][87]

Poland withdrew in 1950—allegedly pressured by the Soviet Union—but returned in 1986. The former Czechoslovakia was expelled in 1954 for "failing to provide required data" and was readmitted in 1990, after the Velvet Revolution.[88]

Qualifications

Any country may apply to be a part of the IMF. Post-IMF formation, in the early postwar period, rules for IMF membership were left relatively loose. Members needed to make periodic membership payments towards their quota, to refrain from currency restrictions unless granted IMF permission, to abide by the Code of Conduct in the IMF Articles of Agreement, and to provide national economic information. However, stricter rules were imposed on governments that applied to the IMF for funding.[22]

The countries that joined the IMF between 1945 and 1971 agreed to keep their exchange rates secured at rates that could be adjusted only to correct a "fundamental disequilibrium" in the balance of payments, and only with the IMF's agreement.[89]

Benefits

Member countries of the IMF have access to information on the economic policies of all member countries, the opportunity to influence other members' economic policies, technical assistance in banking, fiscal affairs, and exchange matters, financial support in times of payment difficulties, and increased opportunities for trade and investment.[90]

Personnel This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "International Monetary Fund" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Board of Governors

The board of governors consists of one governor and one alternate governor for each member country. Each member country appoints its two governors. The Board normally meets once a year and is responsible for electing or appointing an executive director to the executive board. While the board of governors is officially responsible for approving quota increases, special drawing right allocations, the admittance of new members, compulsory withdrawal of members, and amendments to the Articles of Agreement and By-Laws, in practice it has delegated most of its powers to the IMF's executive board.[91]

The board of governors is advised by the International Monetary and Financial Committee and the Development Committee. The International Monetary and Financial Committee has 24 members and monitors developments in global liquidity and the transfer of resources to developing countries.[92] The Development Committee has 25 members and advises on critical development issues and on financial resources required to promote economic development in developing countries.

The board of governors reports directly to the managing director of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva.[92]

Executive Board

24 Executive Directors make up the executive board. The executive directors represent all 189 member countries in a geographically based roster.[93] Countries with large economies have their own executive director, but most countries are grouped in constituencies representing four or more countries.[91]

Following the 2008 Amendment on Voice and Participation which came into effect in March 2011,[94] seven countries each appoint an executive director: the United States, Japan, China, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and Saudi Arabia.[93] The remaining 17 Directors represent constituencies consisting of 2 to 23 countries. This Board usually meets several times each week.[95] The board membership and constituency is scheduled for periodic review every eight years.[96]

show

List of Executive Directors of the IMF, as of February 2019

Managing Director

The IMF is led by a managing director, who is head of the staff and serves as chairman of the executive board. The managing director is the most powerful position at the IMF.[97] Historically, the IMF's managing director has been a European citizen and the president of the World Bank has been an American citizen. However, this standard is increasingly being questioned and competition for these two posts may soon open up to include other qualified candidates from any part of the world.[98][99] In August 2019, the International Monetary Fund has removed the age limit which is 65 or over for its managing director position.[100]

In 2011, the world's largest developing countries, the BRIC states, issued a statement declaring that the tradition of appointing a European as managing director undermined the legitimacy of the IMF and called for the appointment to be merit-based.[98][101]

List of Managing Director

TermDatesNameCitizenshipBackground16 May 1946 – 5 May 1951Camille Gutt BelgiumPolitician, Economist, Lawyer, Economics Minister, Finance Minister23 August 1951 – 3 October 1956Ivar Rooth

BelgiumPolitician, Economist, Lawyer, Economics Minister, Finance Minister23 August 1951 – 3 October 1956Ivar Rooth SwedenEconomist, Lawyer, Central Banker321 November 1956 – 5 May 1963Per Jacobsson

SwedenEconomist, Lawyer, Central Banker321 November 1956 – 5 May 1963Per Jacobsson SwedenEconomist, Lawyer, Academic, League of Nations, BIS41 September 1963 – 31 August 1973Pierre-Paul Schweitzer

SwedenEconomist, Lawyer, Academic, League of Nations, BIS41 September 1963 – 31 August 1973Pierre-Paul Schweitzer FranceLawyer, Businessman, Civil Servant, Central Banker51 September 1973 – 18 June 1978Johan Witteveen

FranceLawyer, Businessman, Civil Servant, Central Banker51 September 1973 – 18 June 1978Johan Witteveen NetherlandsPolitician, Economist, Academic, Finance Minister, Deputy Prime Minister, CPB618 June 1978 – 15 January 1987Jacques de Larosière

NetherlandsPolitician, Economist, Academic, Finance Minister, Deputy Prime Minister, CPB618 June 1978 – 15 January 1987Jacques de Larosière FranceBusinessman, Civil Servant, Central Banker716 January 1987 – 14 February 2000Michel Camdessus

FranceBusinessman, Civil Servant, Central Banker716 January 1987 – 14 February 2000Michel Camdessus FranceEconomist, Civil Servant, Central Banker81 May 2000 – 4 March 2004Horst Köhler

FranceEconomist, Civil Servant, Central Banker81 May 2000 – 4 March 2004Horst Köhler GermanyPolitician, Economist, Civil Servant, EBRD, President97 June 2004 – 31 October 2007Rodrigo Rato

GermanyPolitician, Economist, Civil Servant, EBRD, President97 June 2004 – 31 October 2007Rodrigo Rato SpainPolitician, Businessman, Economics Minister, Finance Minister, Deputy Prime Minister101 November 2007 – 18 May 2011Dominique Strauss-Kahn

SpainPolitician, Businessman, Economics Minister, Finance Minister, Deputy Prime Minister101 November 2007 – 18 May 2011Dominique Strauss-Kahn FrancePolitician, Economist, Lawyer, Businessman, Economics Minister, Finance Minister115 July 2011 – 12 September 2019Christine Lagarde

FrancePolitician, Economist, Lawyer, Businessman, Economics Minister, Finance Minister115 July 2011 – 12 September 2019Christine Lagarde FrancePolitician, Lawyer, Finance Minister121 October 2019 – presentKristalina Georgieva

FrancePolitician, Lawyer, Finance Minister121 October 2019 – presentKristalina Georgieva BulgariaPolitician, Economist

BulgariaPolitician, Economist On 28 June 2011, Christine Lagarde was named managing director of the IMF, replacing Dominique Strauss-Kahn.

On 28 June 2011, Christine Lagarde was named managing director of the IMF, replacing Dominique Strauss-Kahn.

Former managing director Dominique Strauss-Kahn was arrested in connection with charges of sexually assaulting a New York hotel room attendant and resigned on 18 May. The charges were later dropped.[102] On 28 June 2011 Christine Lagarde was confirmed as managing director of the IMF for a five-year term starting on 5 July 2011.[103][104] She was re-elected by consensus for a second five-year term, starting 5 July 2016, being the only candidate nominated for the post of managing director.[105]

France

France

IMF staff

IMF staff have considerable autonomy and are known to shape IMF policy. According to Jeffrey Chwieroth, "It is the staff members who conduct the bulk of the IMF's tasks; they formulate policy proposals for consideration by member states, exercise surveillance, carry out loan negotiations and design the programs, and collect and systematize detailed information."[120] Most IMF staff are economists.[121] According to a 1968 study, nearly 60% of staff were from English-speaking developed countries.[122] By 2004, between 40 and 50% of staff were from English-speaking developed countries.[122]

A 1996 study found that 90% of new staff with a PhD obtained them from universities in the United States or Canada.[122] A 1999 study found that none of the new staff with a PhD obtained their PhD in the Global South.[122]

- all 190 members' quotas will increase from a total of about XDR 238.5 billion to about XDR 477 billion, while the quota shares and voting power of the IMF's poorest member countries will be protected.

- more than 6 percent of quota shares will shift to dynamic emerging market and developing countries and also from over-represented to under-represented members.

- four emerging market countries (Brazil, China, India, and Russia) will be among the ten largest members of the IMF. Other top 10 members are the United States, Japan, Germany, France, the United Kingdom and Italy.[125]

Effects of the quota system[edit]

The IMF's quota system was created to raise funds for loans.[22] Each IMF member country is assigned a quota, or contribution, that reflects the country's relative size in the global economy. Each member's quota also determines its relative voting power. Thus, financial contributions from member governments are linked to voting power in the organization.[124]

This system follows the logic of a shareholder-controlled organization: wealthy countries have more say in the making and revision of rules.[22] Since decision making at the IMF reflects each member's relative economic position in the world, wealthier countries that provide more money to the IMF have more influence than poorer members that contribute less; nonetheless, the IMF focuses on redistribution.[124]

Inflexibility of voting power[edit]

Quotas are normally reviewed every five years and can be increased when deemed necessary by the board of governors. IMF voting shares are relatively inflexible: countries that grow economically have tended to become under-represented as their voting power lags behind.[11] Currently, reforming the representation of developing countries within the IMF has been suggested.[124] These countries' economies represent a large portion of the global economic system but this is not reflected in the IMF's decision-making process through the nature of the quota system. Joseph Stiglitz argues, "There is a need to provide more effective voice and representation for developing countries, which now represent a much larger portion of world economic activity since 1944, when the IMF was created."[126] In 2008, a number of quota reforms were passed including shifting 6% of quota shares to dynamic emerging markets and developing countries.[127]

Overcoming borrower/creditor divide[edit]

The IMF's membership is divided along income lines: certain countries provide financial resources while others use these resources. Both developed country "creditors" and developing country "borrowers" are members of the IMF. The developed countries provide the financial resources but rarely enter into IMF loan agreements; they are the creditors. Conversely, the developing countries use the lending services but contribute little to the pool of money available to lend because their quotas are smaller; they are the borrowers. Thus, tension is created around governance issues because these two groups, creditors and borrowers, have fundamentally different interests.[124]

The criticism is that the system of voting power distribution through a quota system institutionalizes borrower subordination and creditor dominance. The resulting division of the IMF's membership into borrowers and non-borrowers has increased the controversy around conditionality because the borrowers are interested in increasing loan access while creditors want to maintain reassurance that the loans will be repaid.[128]

Use[edit]

A recent[when?] source revealed that the average overall use of IMF credit per decade increased, in real terms, by 21% between the 1970s and 1980s, and increased again by just over 22% from the 1980s to the 1991–2005 period. Another study has suggested that since 1950 the continent of Africa alone has received $300 billion from the IMF, the World Bank, and affiliate institutions.[129]

A study by Bumba Mukherjee found that developing democratic countries benefit more from IMF programs than developing autocratic countries because policy-making, and the process of deciding where loaned money is used, is more transparent within a democracy.[129] One study done by Randall Stone found that although earlier studies found little impact of IMF programs on balance of payments, more recent studies using more sophisticated methods and larger samples "usually found IMF programs improved the balance of payments".[39]

![[ℕ𝕖𝕧𝕖𝕣] 𝕊𝕖𝕝𝕝 𝕐𝕠𝕦𝕣 𝔹𝕚𝕥𝕔𝕠𝕚𝕟 - And Now What.... Pray To The God Of Hopium?](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/79e7827b-c644-4853-b048-a9601a8a8da7/1)

![[LIVE] Engage2Earn: Save our PBS from Trump](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/c23a1a05-c831-4c66-a1d1-96b700ef0450/1)