The Memory Keepers

In Millbrook Haven, every birth came with a gift - or a curse, depending on who you asked. Dr. Sarah Chen had delivered hundreds of babies during her fifteen years at the town's only hospital, and she'd documented every single one of their first words, which invariably weren't "mama" or "dada," but rather names of people they'd never met and places they'd never been.

Today's delivery was no different. As she handed the newborn boy to his mother, Jessica Walsh, she prepared her recorder. It would take anywhere from three to six months before the memories would surface, manifesting in impossible knowledge and strange habits that belonged to someone else's life.

"He's beautiful," Jessica whispered, cradling her son. Her husband Thomas stood nearby, a mixture of joy and apprehension on his face. Like all Millbrook Haven parents, they knew what was coming.

"Have you decided on a name?" Sarah asked, though she knew most parents these days waited until the memories emerged. It helped avoid awkward situations like the Martinez baby who turned out to have memories of a 19th-century Scottish shepherd and refused to respond to anything but "Hamish" for years.

"We're waiting," Thomas replied, squeezing his wife's hand.

Four months later, Sarah received the call she'd been expecting. The Walsh baby had spoken his first words: "Terminal 4, Heathrow." The memories had begun to surface.

Maya Patel ran the Memory Registry, a converted Victorian house on Maple Street where every child's "inherited" memories were documented and cross-referenced. Her office walls were lined with filing cabinets containing decades of records, each telling the story of a stranger's life living inside a child's mind.

"He remembers being a baggage handler," Jessica Walsh explained, bouncing seven-month-old Peter on her knee. They'd named him after her grandfather, hoping family ties might help anchor him to his own life. "He gets upset when we pack suitcases wrong. Yesterday, he started crying when I put my shoes in the same compartment as my clothes."

Maya nodded, her fingers flying across her keyboard. "Any other memories?"

"He hums this song sometimes - Thomas looked it up. It's a Hindi prayer his mother used to sing..." Jessica paused. "Not his mother. The other person's mother."

"Rajesh Kumar," Maya said, pulling up a file. "Born 1962 in Mumbai, died 2019 in London. Worked at Heathrow Airport for thirty-two years." She turned her screen to show them a photograph of a middle-aged Indian man with kind eyes and a mustache. "This is who Peter remembers being."

Jessica studied the photo, trying to reconcile this stranger with her blue-eyed, fair-haired baby. "Will it... will it affect who he becomes?"

Maya had heard this question hundreds of times. "The memories are just one part of who he'll be. Think of them like an extra set of experiences he can draw from. Some kids barely notice them after a while. Others find them useful. Remember Claire Henderson? Her memories of that civil war nurse helped her become one of the best trauma surgeons in the state."

Dr. Chen's own daughter, Lily, was thirteen now and carried the memories of a lighthouse keeper from Nova Scotia. She'd never seen the ocean, but she could describe in perfect detail the way storm waves looked crashing against rocks at midnight, and she knew how to calculate tide tables in her head.

"Mom," Lily said one morning over breakfast, "do you think Margaret would have liked me?"

Sarah looked up from her coffee. Margaret Collins was the name of the woman whose memories lived in Lily's mind. "What makes you ask that?"

"Sometimes I feel guilty, like I'm carrying around pieces of her life without her permission. Like I stole something precious."

Sarah considered this. The ethical implications of their town's unique situation had been debated endlessly since the first documented case in 1952. "I think," she said carefully, "that memories are meant to be preserved. They're meant to teach us something. Margaret's life has helped shape yours, but you're still you, Lily."

The phenomenon had turned Millbrook Haven into a research hub. Scientists came from around the world to study the children, trying to understand how memories could transfer from the recently deceased to the newly born. Some theorized it was quantum entanglement, others suggested cellular memory passed through some unknown mechanism. None of the theories quite explained it.

The town had adapted. The school curriculum included "Memory Integration" classes alongside math and reading. There were support groups for parents and children, and an annual Memory Festival where kids could celebrate and share the lives they remembered. Some families moved away, unable to handle the complexity of raising children with double lives in their heads. Others moved in, fascinated by the possibility.

Peter Walsh was three when he started drawing detailed diagrams of airplane cargo holds. At five, he could direct passengers to their gates in seven different languages. His parents learned to balance nurturing his own interests with acknowledging the skills and memories he'd inherited.

"The trick," Thomas told other parents at support group meetings, "is to treat it like having a very knowledgeable imaginary friend. Sometimes Peter wants to talk about Rajesh's life, and we listen. Other times, he's just our little boy who loves dinosaurs and wants to build rocket ships."

Maya Patel's research had shown that the memories began to fade around puberty, though they never disappeared completely. They became more like old photographs - still there, but less vivid, less immediate. This allowed the teenagers to develop their own identities more fully, while retaining the wisdom and skills they'd inherited.

She documented every case meticulously, noting patterns and correlations. Children who received memories from people who died peacefully tended to be more serene. Those who inherited memories from people who died suddenly often developed acute awareness of danger and strong protective instincts. It wasn't always easy - there were children who struggled with inherited trauma, who needed extra support to process memories of loss or hardship that weren't their own.

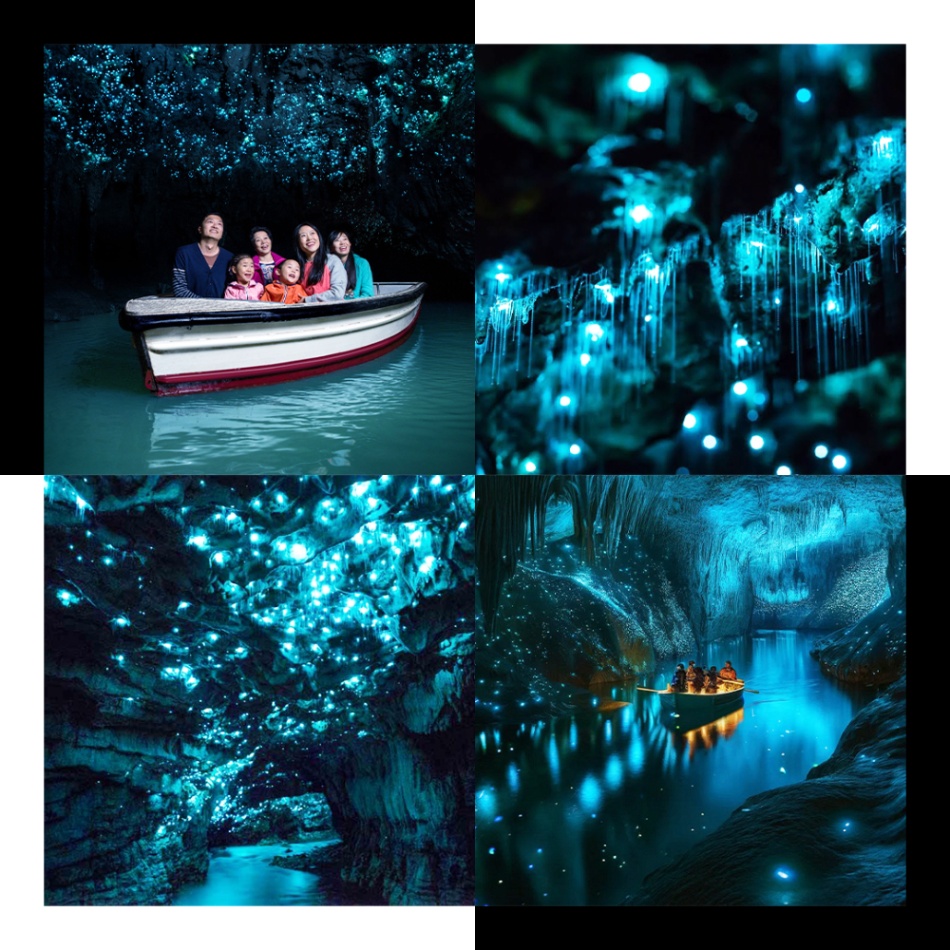

When Peter turned seven, his parents took him to London. They stood outside Heathrow's Terminal 4, watching planes take off and land.

"It looks different now," Peter said softly. "They've changed the employee entrance." Then he pointed to a bench near the taxi stand. "That's where he used to eat lunch every day. He could see the planes from there."

Jessica squeezed his hand. "Would you like to sit there for a while?"

Peter nodded. As they sat on the bench, he pulled out a small container of curry his mother had packed - Rajesh's favorite recipe, which Peter had recited to her from memory.

"Sometimes," Peter said between bites, "I think Rajesh would be happy that I remember him. He didn't have any children of his own, but he loved his job. He loved helping people find their way home."

The Memory Registry had a wall of photographs - hundreds of faces of the remembered ones, paired with pictures of the children who carried their memories. Maya often stood before this wall, contemplating the strange tapestry of interconnected lives.

"We're all just stories in the end," she told a reporter once. "In most places, when someone dies, their personal memories - the small details that made up their daily lives - die with them. Here, they live on. Every baby born in Millbrook Haven ensures that someone's story continues."

Dr. Chen recorded it all: Peter's first words about Heathrow, his early aptitude for languages, the way he arranged his toys with careful precision. She added his file to the thousands of others, each documenting this remarkable inheritance of memory.

One day, she knew, scientists might understand the mechanism behind it all. But for now, Millbrook Haven remained a place where death wasn't quite an ending and birth wasn't quite a beginning. It was a place where memories flowed like water between vessels, where the boundaries between lives blurred and reformed, where every child carried within them the gift of another's lifetime.

As she watched Peter growing up, balancing his own personality with Rajesh's memories, she thought about how each generation in their town was a bridge between past and present. These children were memory keepers, story carriers, living libraries of human experience.

And perhaps that was the real gift - not the memories themselves, but the understanding they brought: that every life, no matter how ordinary it might seem, was worth remembering. That every person's story deserved to be carried forward, to be honored and preserved in the most human way possible - through the laughter, tears, and wonder of a child.

In Millbrook Haven, no one's story ever truly ended. They just became part of a larger narrative, passed down like precious heirlooms, shaping new lives while honoring those that came before. And in this way, the town itself became a living memory, a place where the past and present danced together in an eternal, beautiful choreography of remembered lives.