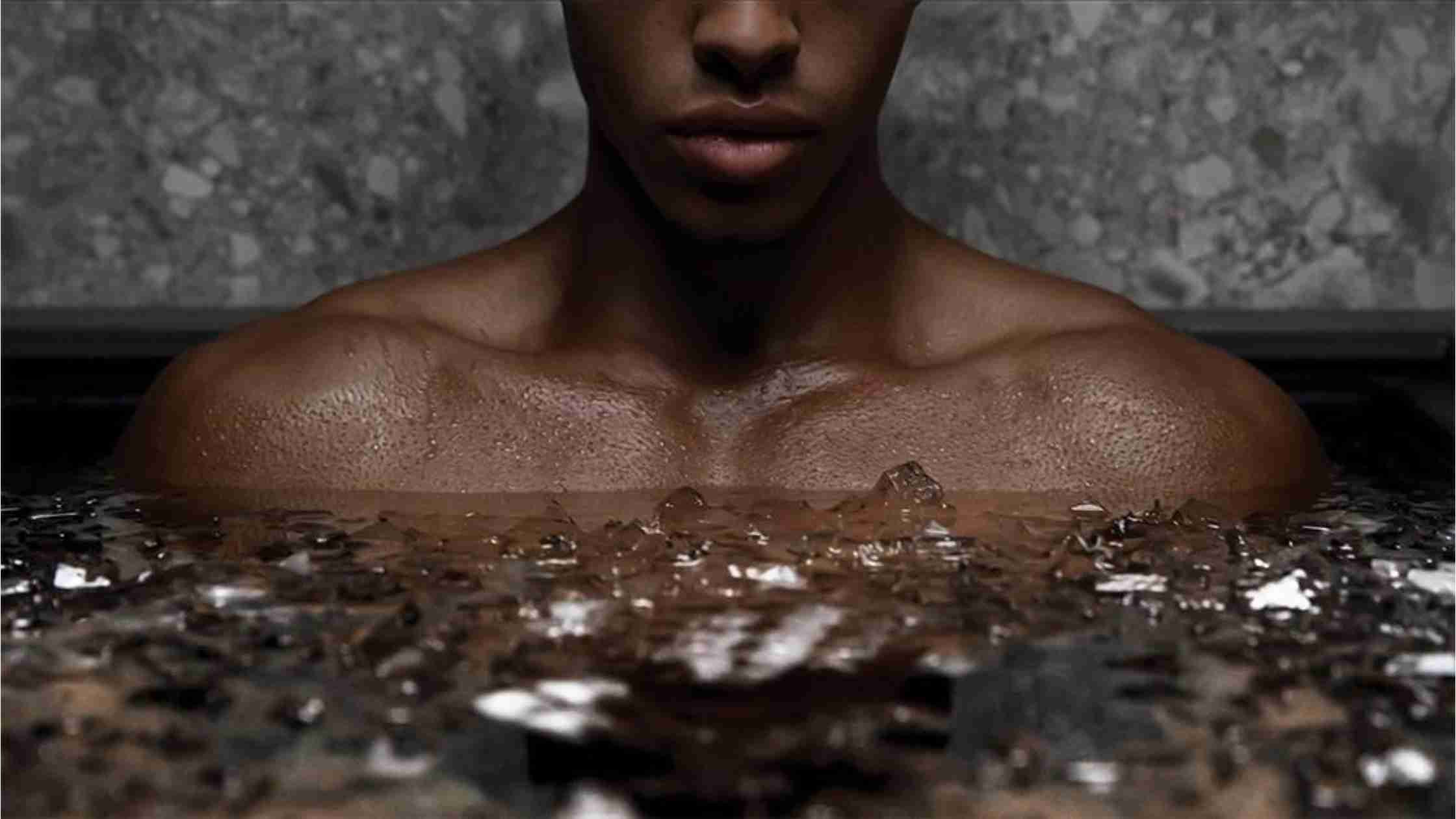

Cold Plunge

This is what a cold plunge does to your body Enthusiasts claim that swimming in icy water can do wonders for your blood pressure, metabolism, and mental health. We asked experts to weigh the evidence.

Susan Ringwood greets all guests at her Scottish cottage with a simple invitation: to join her in an ocean swim. Her offer isn’t limited to the summer months, either. Ringwood and her husband Gary swim in the North Atlantic year-round, enjoying the tranquility and solitude that accompanies their endeavors.

“To me, it’s about the water. It’s an immersive experience,” she says.

Ringwood simply calls her hobby “swimming,” but wellness influencers and winter aficionados alike have begun to promote polar plunges and cold-water swimming as an antidote to everything from depression to diabetes.

While cold plunges have a long history and a newfound enthusiasm, physiologists say that there’s not much evidence supporting the claims of these health benefits.

Nor is the activity without risk. Extreme temperature shifts and strain on the cardiovascular system can potentially trigger heart attacks, even death, says François Haman, a physiologist at the University of Ottawa in Canada.

“It’s actually extremely dangerous, mainly because everything most people know is from social media. There's very little knowledge around it,” Haman says. “It’s the biggest jolt a human can experience—like a bolt of lightning. That’s how dangerous it is. You can go into cardiac arrest.”

Here’s what the field’s leading experts have to say about the health risks and benefits of cold swimming and polar plunges, and how to participate safely.

When did cold plunges become a health trend?

Diving into cold water has a long history in Scandinavia, where people have touted the therapeutic benefits of these activities for centuries. Cold swimming really took off globally during the pandemic lockdowns of 2020.

“It was an activity that people could do relatively safely outdoors together, without having too much direct contact,” says James Mercer, a physiologist at the University of Tromsø in Norway. “For many people, it’s a social activity.”

On social media, many aficionados shared how the cold dips improved their mood and health—and a global phenomenon was born.

.png)

How does cold water affect your body?

When your body encounters cold water, it can be shocking—literally. Physiologists call this the “cold shock” response. Temperature receptors in your skin sense the frigid water, triggering the constriction of blood vessels in your extremities to preserve heat in the body’s core. This causes you to gasp for air and your heart rate to skyrocket.

“The first few moments after you enter the water, that’s probably the most dangerous part,” says Lee Hill, a former swim coach and exercise physiologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. “If you’re not ready for the cold shock, it can be really, really dangerous.”

It’s a powerful response, Haman agrees, and in his work with the military and special forces of several nations, he coaches participants to exhale as they hit the water, to counteract the primitive gasping response.

While the initial cold response leads to an increase in heart rate and blood pressure, those changes reverse after several minutes. Known as the mammalian diving response, breathing and blood pressure begin to slow down to below normal levels. It’s an ancient evolutionary response, and it’s been best studied in marine mammals that can dive to astonishing depths.

Physiologists believe this response helps to conserve oxygen— crucial when you’re holding your breath for long periods.

The diving response also helps conserve heat by continuing to push blood to the vital organs and away from the extremities.

“We call this vasoconstriction, and it’s the first line of defense when you get cold,” Mercer says.

Experts say that being in cold water is more dangerous than cold air. Water conducts heat much more effectively than air, meaning that it can draw the heat from your body more quickly and efficiently, Mercer says. You can become hypothermic swimming in any water that’s below your body’s natural temperature if you stay in long enough.

A person’s size, metabolism, and body fat percentage all play a role in how long someone can safely remain in cold water, Mercer says.

Are there health benefits of cold plunges?

According to proponents, cold plunges can improve blood pressure and insulin sensitivity, as well as decreasing inflammation, improving immunity, and benefitting metabolism. It might also help relieve arthritis pain.

But while there is some scientific research to back up these claims, Denis Blondin, a thermal physiologist at the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec, says that many of these studies included only a small number of participants who were overwhelmingly young men of European descent, which limits what scientists can say more broadly and in other populations.

There’s also a lot of variation in the temperature of the water used, duration of immersion, and the setting of the immersion (in a lab versus outdoors). All these differences make it hard to compare different studies, Blondin points out.

“There’s a lot that we don’t know, and I would say most of the stuff we see in podcasts and such are not things that are definitive and set in stone. We find they tend to over-extrapolate things,” he says.

Are there mental health benefits?

Ringwood says that going for a swim helps her mentally wash away her worries.

“It’s joyous. It takes all my stresses and puts them in the water. I let it wash concerns into the sea,” Ringwood says.

Haman agrees. He, too, finds the experience meditative, as do the armed forces members he has trained. The experience forces them to focus on their breathing and other sensations in the present moment, a habit that psychologists call mindfulness.

Studies have shown that activities like polar plunges and cold showers may help reduce depression. Even a single cold dunk has mood-boosting properties. Haman attributes this benefit not only to mindfulness, but also to increases in “feel-good” brain chemicals like dopamine that the brain produces during cold immersion. He says people also experience a post-polar reduction in the stress hormone cortisol.

What to consider when taking the plunge

Bundle up, experts say. This doesn’t necessarily mean wearing a wetsuit—to cold aficionados, it somewhat defeats the purpose—but wearing a warm hat and keeping dry clothes and towels ready for when you get out of the water. Ringwood also wears neoprene gloves to keep her hands more flexible, which enables her to change out of her swimsuit more quickly when she’s done.

For those new to the sport, Haman recommends starting slowly, getting used to colder water during the fall rather than jumping in during a deep freeze.

“Every human responds to cold differently,” he says. “Cold exposure is not one size fits all.”

And how do you know when it’s time to get out?

Your hands and feet are more cold-tolerant than your trunk, due to the high oxygen and nutrient needs of vital organs. As a result, the extremities can cool markedly without impacting the body’s core temperature. These reflexes and alterations are incredibly powerful, but even they have their limits. If the body’s inner temperature starts dropping, then it’s time to get out of the water and get warmed up—fast.

The best way to determine if you’ve hit this point is by understanding shivering. Mild shivering in the limbs—caused when your muscles rapidly tighten and relax—is an efficient way for the body to generate heat. Shivering from more central muscle groups is stronger and far more uncomfortable. This is a sign that you’re getting too cold and it’s crucial to start warming up before you lose muscle control.

“If you’ve stopped shivering, your ability to actually generate heat has now stopped,” Hill says. “A light bulb should go off that something is starting to go a little bit south.”

Source

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/10/08/1204411415/cold-plunge-health-benefits-how-to

https://www.forbes.com/health/wellness/cold-plunge-what-to-know/

https://www.mayoclinichealthsystem.org/hometown-health/speaking-of-health/cold-plunge-after-workouts

https://www.vogue.com/article/cold-shower-benefits

https://www.everydayhealth.com/wellness/cold-water-therapy/guide/