Oysters: The luxury delicacy that was once a fast-food fad

As the United States underwent industrialization, urban workers relied heavily on oysters as a dietary staple. However, the perception of oysters shifted from being a common, everyday food to a luxury item over time.

As the United States underwent industrialization, urban workers relied heavily on oysters as a dietary staple. However, the perception of oysters shifted from being a common, everyday food to a luxury item over time.

In the 18th and 19th centuries in both Europe and North America, oysters were widely consumed as a basic and affordable protein source. They were not only served as a customary appetizer at fancy banquets but also featured in everyday meals, such as stews and baked dishes. Similar to eggs today, oysters were readily available and accessible to people of all socioeconomic backgrounds.

By the 19th century, oysters were being cultivated within American cities, making them even more accessible to urban populations. While wild oysters had been consumed for centuries, the abundance of North American oysters surprised early European visitors. However, the European oyster species had already become a rarity and elite food by this time, with working-class individuals in cities like London no longer consuming it.

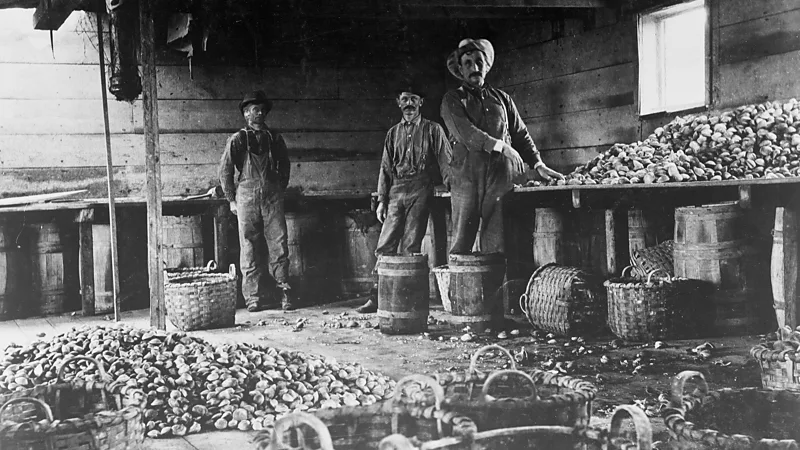

Overall, oysters transitioned from being a ubiquitous and affordable food to a symbol of luxury and exclusivity, reflecting changes in cultural perceptions and availability over time. The American industrial oyster industry emerged in the mid-to-late 18th century, characterized by the mass production of oysters through professional cultivation methods. Entrepreneurs specialized in harvesting oyster seeds, which were then spread across the floors of bays and estuaries to grow. These seed oysters could be transported nationwide by train and then placed into water to mature. New York State began leasing seabed sections to individual growers in 1855, enabling the formation of oyster farms. The intensity of oyster farming was such that New York City alone produced 700 million oysters by 1880.

The American industrial oyster industry emerged in the mid-to-late 18th century, characterized by the mass production of oysters through professional cultivation methods. Entrepreneurs specialized in harvesting oyster seeds, which were then spread across the floors of bays and estuaries to grow. These seed oysters could be transported nationwide by train and then placed into water to mature. New York State began leasing seabed sections to individual growers in 1855, enabling the formation of oyster farms. The intensity of oyster farming was such that New York City alone produced 700 million oysters by 1880.

During this period, the wealthiest individuals in Staten Island became prominent oyster growers, investing in waterfront real estate, naming streets after themselves, and constructing grand wooden mansions. However, oyster panics eventually ensued, leading to significant challenges for the industry.

Despite the awareness that oysters could pose health risks, the wealthy attempted to safeguard themselves by purchasing oysters from dealers who claimed to cultivate them in clean water, while the less affluent cooked their oysters as a precaution. However, in 1854, The New York Times editors condescendingly dismissed those who were avoiding oysters due to a series of mysterious deaths, asserting that they had recently consumed oysters without any ill effects.

In reality, oysters grown in water contaminated with human waste, which was common in the urban oyster beds of the 19th century, could easily harbor lethal bacteria. Booker recounts a tragic incident at Wesleyan College in Connecticut, where a fraternity meal of oysters sickened approximately 22 people with typhoid, resulting in the deaths of six young men. A subsequent investigation by a biology professor determined that the oysters were responsible for the outbreak.

In 1924, a typhoid epidemic affected 1,500 Americans in Chicago, New York, and Washington DC, with oysters identified as the source of the outbreak. This incident resulted in the deaths of 150 people, making it the deadliest food-borne outbreak in US history, according to Food Safety News. While water pollution levels had increased, advancements in forensic investigation methods also contributed to the recognition that urban oysters posed a significant health risk. According to Booker, the peak of oyster consumption occurred around 1910, after which their popularity declined significantly. Oysters are no longer considered a staple food for the average person. Even during my time as a teenage docent at the local historical museum, I portrayed oysters as a luxurious and expensive delicacy in a distant gold rush-era café, despite their former affordability.

According to Booker, the peak of oyster consumption occurred around 1910, after which their popularity declined significantly. Oysters are no longer considered a staple food for the average person. Even during my time as a teenage docent at the local historical museum, I portrayed oysters as a luxurious and expensive delicacy in a distant gold rush-era café, despite their former affordability.

However, in the 1850s, oysters were not as rarefied, and items like eggs and bacon were likely considered more expensive due to the logistical challenges of transportation in the early days of the California goldfields.

With advancements in water cleanliness regulations in the 20th century, there is potential for oyster farming to be reintroduced in urban areas, providing a sustainable source of protein for city dwellers. Efforts to revive oyster reefs as a food source are underway, as they also benefit coastal habitats.

While Booker is doubtful that people could easily perceive urban waters as a clean source of food, he appreciates the concept. With proper regulation and management, he believes that oyster populations could thrive once again in cities known for their abundance of oysters.