The Society of SpectacleThe Culture Industry won, get over it

When French sociologist Guy Debord wrote “The Society of Spectacle” in 1967, his goal was to describe, and denounce, the advertising, public relations and celebrity-dictated consumer culture. The premise of Debord’s analysis is that “being is replaced by having, and having is replaced by appearing. We no longer live, we aspire, signal, perform.”

When French sociologist Guy Debord wrote “The Society of Spectacle” in 1967, his goal was to describe, and denounce, the advertising, public relations and celebrity-dictated consumer culture. The premise of Debord’s analysis is that “being is replaced by having, and having is replaced by appearing. We no longer live, we aspire, signal, perform.”

A recent New Yorker’s article, “The Case Against Travel” would agree, but Debord wrote his book before the Internet, suggesting that culture in capitalism — regardless of technology — inevitably leads towards appearances, performance and commodity.

For Bernard Arnault, owner of LVMH, culture is a superstar commodity. Not satisfied with being a mere fashion house, Arnault set his sights on turning Louis Vuitton into a house of culture.

Creativity vs Originality

Cultural products like Ghostbusters 2, Mission Impossible 17, Barbie Movie, Y2K mood, or Marvel Universe depict capitalism as a deeply uncreative system. Nothing new ever happens: creativity is in curating, reviving and repurposing the past, putting it in new contexts and giving it new interpretations.

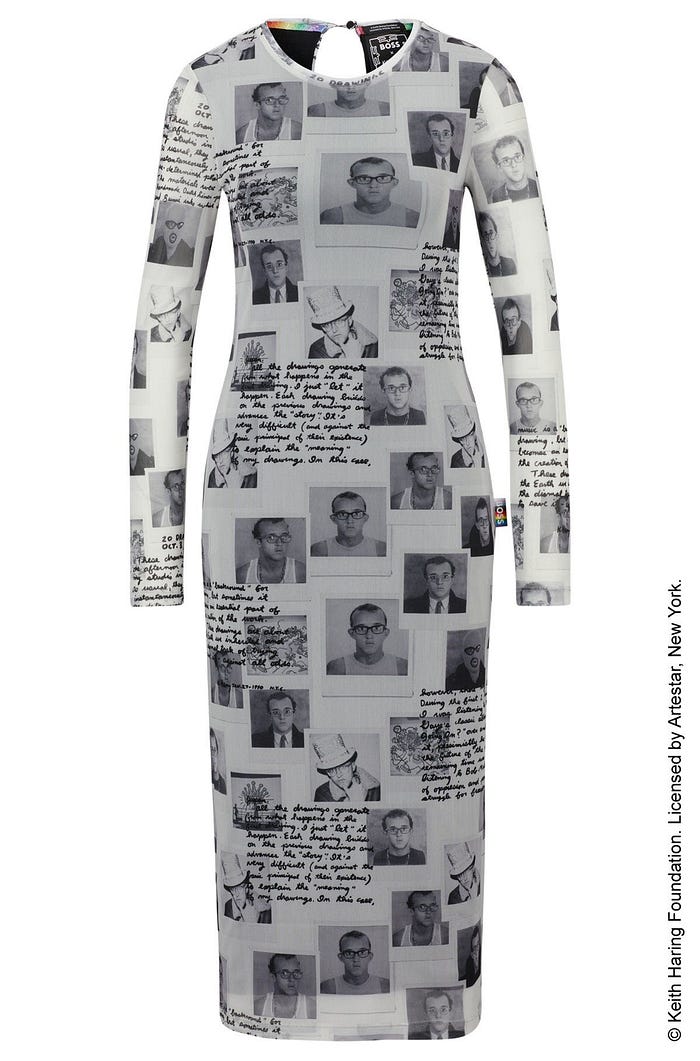

Whereas reinterpretation has always been the engine of culture, it used to go in the opposite direction: conventional ideas were re-contextualized as radical (a corset in the 1990s, Marc Jacobs artistic collaborations). Today, once-radical ideas are made conventional. Places, times and personalities are all a potential commercial inspiration — a reference: Harlem’s history of bootlegging, indie sleaze, Basquiat’s art and Keith Haring, whose face can these days be found on a Boss dress. If modern creativity is in representing the past as new, then the power of that representation rests on celebrity. For Debord, both are commodities: “The celebrity, the spectacular representation of a living human being, embodies the banality of embodying the image of a possible role. Their individuality is sacrificed in order to become a figurehead of the profit-driven system,” and “The star is the object of identification with the shallow seeming life that has to compensate for the fragmented productive specializations which are actually lived. Celebrities are commodities themselves.” Both past and celebrity also have proven success rate. The model of reinvention and re-appropriation rests on one source code, and its innumerable sequels. There’s only one genre in the society of spectacle: the genre of a brand universe.

If modern creativity is in representing the past as new, then the power of that representation rests on celebrity. For Debord, both are commodities: “The celebrity, the spectacular representation of a living human being, embodies the banality of embodying the image of a possible role. Their individuality is sacrificed in order to become a figurehead of the profit-driven system,” and “The star is the object of identification with the shallow seeming life that has to compensate for the fragmented productive specializations which are actually lived. Celebrities are commodities themselves.” Both past and celebrity also have proven success rate. The model of reinvention and re-appropriation rests on one source code, and its innumerable sequels. There’s only one genre in the society of spectacle: the genre of a brand universe.

Sequels vs Knock-Offs

Just like there is Marvel Cinematic Universe, there’s Arnault Fashion Universe, with the interconnected set of characters, self-referential narrative lines, and methodical rollouts in categories ranging from hospitality to lifestyle to fashion to travel, making it unnecessary to ever leave it.

Like Marvel’s IP, which gives Disney something to do and money to make for decades to come, LVMH’s seventy five brands provide a nearly-infinite IP. Call Damier Damouflage and you just gave it a new life; bring back once-popular saddle bag and watch the sales soar.

These endless fashion sequels create a new dynamics in the market: they turn knockoffs into the most original products around. Not only knockoffs display now-enviable craftsmanship, they also do not pretend to be anything else but the imitation of the original. Spare us the faux references and give us the real replica.

Parochialism vs Humor

Arnault cultural ambition is not original. It is also parochial.

“Everything I say is a joke. I am like a caricature of myself, and I like that. It is like a mask,” the late Karl Lagerfeld famously said. “And for me the Carnival of Venice lasts all year long.” Lagerfeld was in on his own joke, and this made Chanel irreverent and and coveted and unwaveringly relevant. Lagerfeld mastered the art of detournement — or hijacking — the Spectacle by taking it to the extreme and turning it into a caricature. Evian bottle holders, space ships, icebergs, supermarkets, Choupette — Chanel’s Spectacle has been powered by humor, parody, irony and satire.

Lagerfeld was in on his own joke, and this made Chanel irreverent and and coveted and unwaveringly relevant. Lagerfeld mastered the art of detournement — or hijacking — the Spectacle by taking it to the extreme and turning it into a caricature. Evian bottle holders, space ships, icebergs, supermarkets, Choupette — Chanel’s Spectacle has been powered by humor, parody, irony and satire.

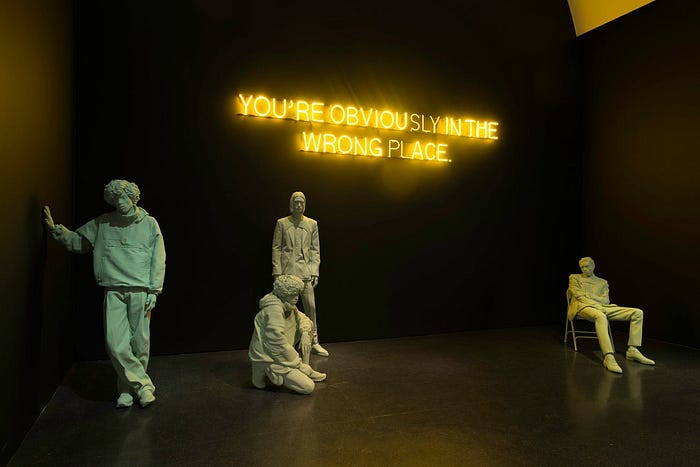

Today, creative collective MSCHF does something similar, mocking commercial symbolism through its own language. The late Virgil Abloh, referenced Surrealists (for some, the last original art form in capitalism) to make fun of the spectacle and then framed his jokes in a museum. Without a certain lack of respect, brands turn into a dogma. “Waves of enthusiasm for a given product,” writes Debord, resemble “moments of fervent exaltation similar to the miracles of the old religious fetishism.” Without humor and nuance, brands trivialize the original intention behind their references: bootlegging, subculture, subversion, critique turn into the mainstream, ready-for-sale. What was once an act of subversion and social critique is becomes buttery leather.

Without a certain lack of respect, brands turn into a dogma. “Waves of enthusiasm for a given product,” writes Debord, resemble “moments of fervent exaltation similar to the miracles of the old religious fetishism.” Without humor and nuance, brands trivialize the original intention behind their references: bootlegging, subculture, subversion, critique turn into the mainstream, ready-for-sale. What was once an act of subversion and social critique is becomes buttery leather.

So what?

“If I hadn’t been in fashion, I would have been in advertising,” said Lagerfeld. This attitude was visible in his own comportment as much as in Chanel’s weltanschauug. One never knew where the cultural stopped and the commercial started, and that was the point.

In the course of his career, Alexandre de Betak displayed similar sensibility. “My duty is to create a means of expression that will help translate the creations of the fashion designers: to make them be understood and memorized in a moving manner, not just intellectually or conceptually, but also emotionally,” Betak says in his book Betak: Fashion Show Revolution. At its best, the Spectacle is a display of design excellence. It sells, wows, and communicates the brand image. It is another canvas for brand expression, combining multiple marketing executions into one: event, live-streaming, celebrities and influencers, social media, content, entertainment. Per Betak: “I think that the fashion show as a live event will last a very long time, because people always want to be inspired and encouraged to dream, and there is no limit to all the elements you can employ in a live show — the potential for creativity is boundless.”

At its best, the Spectacle is a display of design excellence. It sells, wows, and communicates the brand image. It is another canvas for brand expression, combining multiple marketing executions into one: event, live-streaming, celebrities and influencers, social media, content, entertainment. Per Betak: “I think that the fashion show as a live event will last a very long time, because people always want to be inspired and encouraged to dream, and there is no limit to all the elements you can employ in a live show — the potential for creativity is boundless.”

The Spectacle is the next phase of branding.

In it, the presentation has to be more memorable and relevant than what has been presented; the presentation is the product.

Unlike production of a product, production of a presentation takes all individual contributions and skillsets and mixes them together; individual expertise matters only in function of the presentation.

In the post-industrial economy, this reversal doesn’t come as a surprise. Just as capitalism commodified products, rendering them interchangeable, advanced capitalism commodifies experiences and perceptions. Once we ran out of things to produce, we turned towards production of experiences: tourism, sports, fashion.

Luxury has, for long, been excluded from this logic of commodification. Luxury’s heritage and cultural role prevented its goods to be perceived as interchangeable; Chanel has a story, Hermès has a story, Saint Laurent has a story. The business model powering it all is genius: items are sold at a steep multiples of the cost of their production.

Arnault did is to take this model to the extreme. In luxury, craftsmanship and branding have always been intertwined; the value of a product was never just craftsmanship (otherwise, we’d be all buying artisanal goods); it was branding (story) plus craftsmanship. Once craftsmanship has been offloaded to China, India or Turkey, luxury is left with branding.

(Not all luxury: Hermès, which still hand-makes its bags in France, does not have a marketing department. But they also say, “We are not luxury. We are high quality.”)

Branding as the Spectacle require superior production and performance. A brand’s ability to put on a show is how its products are going to be valued and how desirable they will be. Arnault figured out that, in the society of performances, a brand with the highest Spectacle credentials wins. He is also one of the few who can actually afford the Spectacle.

Do not hate the player, hate the game.

As a performance, a recent LV Menswear show has been incredibly successful, with 15M YouTube views. This matters. Performance culture is a culture shaped by performance metrics, including consumer engagement metrics and business metrics. With each consequent Spectacle, a new performance standard is set; and the industry is moving further and further into the branding territory.

This market dynamics introduces a new business strategy, across luxury fashion organizations. Designers, who first became Creative Directors, are now Producers. Their job is to produce fashion shows, imagery and content, create buzz and grab as much attention as possible.

Those who are unwilling — or unable — to produce Spectacle will have to content themselves with being summoned by the Producer to bow at the end of the show.

If you enjoyed this analysis, subscribe to The Sociology of Business.

![[ℕ𝕖𝕧𝕖𝕣] 𝕊𝕖𝕝𝕝 𝕐𝕠𝕦𝕣 𝔹𝕚𝕥𝕔𝕠𝕚𝕟 - Is Trump Dying? Or Only Killing The Market?](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/a129e75e-4fa1-46cc-80b6-04e638877e46/1)

![[LIVE] Engage2Earn: McEwen boost for Rob Mitchell](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/c798d46f-d3b8-4a66-bf48-7e1ef50b4338/1)