Cleopatra

Cleopatra

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Cleopatra (disambiguation).

Cleopatra The Berlin Cleopatra, a Roman sculpture of Cleopatra wearing a royal diadem, mid-1st century BC (around the time of her visits to Rome in 46–44 BC), discovered in an Italian villa along the Via Appia and now located in the Altes Museum in Germany[1][2][3][note 1]

The Berlin Cleopatra, a Roman sculpture of Cleopatra wearing a royal diadem, mid-1st century BC (around the time of her visits to Rome in 46–44 BC), discovered in an Italian villa along the Via Appia and now located in the Altes Museum in Germany[1][2][3][note 1]

PharaohQueen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom

Reign51–30 BC (21 years)[4]Coregencyshow

See list

PredecessorPtolemy XII AuletesSuccessorArsinoe IV (disputed, Cleopatra later usurped her from power), Ptolemy XV[note 2]show

- ConsortsPtolemy XIII Theos Philopator

- Ptolemy XIV

- Mark Antony

- ChildrenCaesarion

- Alexander Helios

- Cleopatra Selene II

- Ptolemy Philadelphus

FatherPtolemy XII AuletesMotherPresumably Cleopatra V Tryphaena[note 3]BornEarly 69 BC or Late 70 BC

Alexandria, Ptolemaic KingdomDied10 August 30 BC (aged 39)[note 4]

Alexandria, Roman EgyptBurialUnlocated tomb

- (probably in Egypt)DynastyPtolemaic dynasty

Part of a series onCleopatra VIIEarly lifeDeath

Part of a series onCleopatra VIIEarly lifeDeath - ChildrenAncestry

- Siege of AlexandriaBattle of the Nile

- AccessionAssassination of Pompey

- Liberators' civil warDonations of Alexandria

- Battle of ActiumDownfall

vte

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (Koinē Greek: Κλεοπάτρα Θεά Φιλοπάτωρ[note 5] lit. Cleopatra "father-loving goddess";[note 6] 70/69 BC – 10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler.[note 7] A member of the Ptolemaic dynasty, she was a descendant of its founder Ptolemy I Soter, a Macedonian Greek general and companion of Alexander the Great.[note 8] After the death of Cleopatra, Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire, marking the end of the last Hellenistic-period state in the Mediterranean and of the age that had lasted since the reign of Alexander (336–323 BC).[note 9] Her first language was Koine Greek, and she was the only known Ptolemaic ruler to learn the Egyptian language.[note 10]

In 58 BC, Cleopatra presumably accompanied her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes, during his exile to Rome after a revolt in Egypt (a Roman client state) allowed his rival daughter Berenice IV to claim his throne. Berenice was killed in 55 BC when Ptolemy returned to Egypt with Roman military assistance. When he died in 51 BC, the joint reign of Cleopatra and her brother Ptolemy XIII began, but a falling-out between them led to an open civil war. After losing the 48 BC Battle of Pharsalus in Greece against his rival Julius Caesar (a Roman dictator and consul) in Caesar's civil war, the Roman statesman Pompey fled to Egypt. Pompey had been a political ally of Ptolemy XII, but Ptolemy XIII, at the urging of his court eunuchs, had Pompey ambushed and killed before Caesar arrived and occupied Alexandria. Caesar then attempted to reconcile the rival Ptolemaic siblings, but Ptolemy's chief adviser, Potheinos, viewed Caesar's terms as favoring Cleopatra, so his forces besieged her and Caesar at the palace. Shortly after the siege was lifted by reinforcements, Ptolemy XIII died in the Battle of the Nile; Cleopatra's half-sister Arsinoe IV was eventually exiled to Ephesus for her role in carrying out the siege. Caesar declared Cleopatra and her brother Ptolemy XIV joint rulers but maintained a private affair with Cleopatra that produced a son, Caesarion. Cleopatra traveled to Rome as a client queen in 46 and 44 BC, where she stayed at Caesar's villa. After Caesar's assassination, followed shortly afterwards by that of Ptolemy XIV (on Cleopatra's orders), she named Caesarion co-ruler as Ptolemy XV.

In the Liberators' civil war of 43–42 BC, Cleopatra sided with the Roman Second Triumvirate formed by Caesar's grandnephew and heir Octavian, Mark Antony, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. After their meeting at Tarsos in 41 BC, the queen had an affair with Antony which produced three children. He carried out the execution of Arsinoe at her request, and became increasingly reliant on Cleopatra for both funding and military aid during his invasions of the Parthian Empire and the Kingdom of Armenia. The Donations of Alexandria declared their children rulers over various erstwhile territories under Antony's triumviral authority. This event, their marriage, and Antony's divorce of Octavian's sister Octavia Minor led to the final war of the Roman Republic. Octavian engaged in a war of propaganda, forced Antony's allies in the Roman Senate to flee Rome in 32 BC, and declared war on Cleopatra. After defeating Antony and Cleopatra's naval fleet at the 31 BC Battle of Actium, Octavian's forces invaded Egypt in 30 BC and defeated Antony, leading to Antony's suicide. When Cleopatra learned that Octavian planned to bring her to his Roman triumphal procession, she killed herself by poisoning, contrary to the popular belief that she was bitten by an asp.

Cleopatra's legacy survives in ancient and modern works of art. Roman historiography and Latin poetry produced a generally critical view of the queen that pervaded later Medieval and Renaissance literature. In the visual arts, her ancient depictions include Roman busts, paintings, and sculptures, cameo carvings and glass, Ptolemaic and Roman coinage, and reliefs. In Renaissance and Baroque art, she was the subject of many works including operas, paintings, poetry, sculptures, and theatrical dramas. She has become a pop culture icon of Egyptomania since the Victorian era, and in modern times, Cleopatra has appeared in the applied and fine arts, burlesque satire, Hollywood films, and brand images for commercial products.

Etymology

The Latinized form Cleopatra comes from the Ancient Greek Kleopátra (Κλεοπάτρα), meaning "glory of her father",[5] from κλέος (kléos, "glory") and πατήρ (patḗr, "father").[6] The masculine form would have been written either as Kleópatros (Κλεόπατρος) or Pátroklos (Πάτροκλος).[6] Cleopatra was the name of Alexander the Great's sister Cleopatra of Macedonia, as well as the wife of Meleager in Greek mythology, Cleopatra Alcyone.[7] Through the marriage of Ptolemy V Epiphanes and Cleopatra I Syra (a Seleucid princess), the name entered the Ptolemaic dynasty.[8][9] Cleopatra's adopted title Theā́ Philopátōra (Θεᾱ́ Φιλοπάτωρα) means "goddess who loves her father".[10][11][note 11]

Background

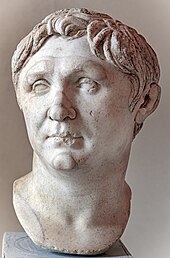

Hellenistic portrait of Ptolemy XII Auletes, the father of Cleopatra, in the Louvre, Paris[12]

Hellenistic portrait of Ptolemy XII Auletes, the father of Cleopatra, in the Louvre, Paris[12]

Ptolemaic pharaohs were crowned by the Egyptian high priest of Ptah at Memphis, but resided in the multicultural and largely Greek city of Alexandria, established by Alexander the Great.[13][14][15][note 12] They spoke Greek and governed Egypt as Hellenistic Greek monarchs, refusing to learn the native Egyptian language.[16][17][18][note 10] In contrast, Cleopatra could speak multiple languages by adulthood and was the first Ptolemaic ruler known to learn the Egyptian language.[19][20][18][note 13] Plutarch implies that she also spoke Ethiopian, the language of the "Troglodytes", Hebrew (or Aramaic), Arabic, the Syrian language (perhaps Syriac), Median, and Parthian, and she could apparently also speak Latin, although her Roman contemporaries would have preferred to speak with her in her native Koine Greek.[20][18][21][note 14] Aside from Greek, Egyptian, and Latin, these languages reflected Cleopatra's desire to restore North African and West Asian territories that once belonged to the Ptolemaic Kingdom.[22]

Roman interventionism in Egypt predated the reign of Cleopatra.[23][24][25] When Ptolemy IX Lathyros died in late 81 BC, he was succeeded by his daughter Berenice III.[26][27] With opposition building at the royal court against the idea of a sole reigning female monarch, Berenice III accepted joint rule and marriage with her cousin and stepson Ptolemy XI Alexander II, an arrangement made by the Roman dictator Sulla.[26][27] Ptolemy XI had his wife killed shortly after their marriage in 80 BC, and was lynched soon after in the resulting riot over the assassination.[26][28][29] Ptolemy XI, and perhaps his uncle Ptolemy IX or father Ptolemy X Alexander I, willed the Ptolemaic Kingdom to Rome as collateral for loans, so that the Romans had legal grounds to take over Egypt, their client state, after the assassination of Ptolemy XI.[26][30][31] The Romans chose instead to divide the Ptolemaic realm among the illegitimate sons of Ptolemy IX, bestowing Cyprus on Ptolemy of Cyprus and Egypt on Ptolemy XII Auletes.[26][28]

Biography

Early childhood

Main article: Early life of Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII was born in early 69 BC to the ruling Ptolemaic pharaoh Ptolemy XII and an uncertain mother,[32][33][note 15] presumably Ptolemy XII's wife Cleopatra V Tryphaena (who may have been the same person as Cleopatra VI Tryphaena),[34][35][36][note 16][note 3] the mother of Cleopatra's older sister, Berenice IV Epiphaneia.[37][38][39][note 17] Cleopatra Tryphaena disappears from official records a few months after the birth of Cleopatra in 69 BC.[40][41] The three younger children of Ptolemy XII, Cleopatra's sister Arsinoe IV and brothers Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator and Ptolemy XIV,[37][38][39] were born in the absence of his wife.[42][43] Cleopatra's childhood tutor was Philostratos, from whom she learned the Greek arts of oration and philosophy.[44] During her youth Cleopatra presumably studied at the Musaeum, including the Library of Alexandria.[45][46]

Reign and exile of Ptolemy XII

Main article: Early life of Cleopatra

Further information: First Triumvirate Most likely a posthumously painted portrait of Cleopatra with red hair and her distinct facial features, wearing a royal diadem and pearl-studded hairpins, from Roman Herculaneum, Italy, 1st century AD[47][48][note 18]

Most likely a posthumously painted portrait of Cleopatra with red hair and her distinct facial features, wearing a royal diadem and pearl-studded hairpins, from Roman Herculaneum, Italy, 1st century AD[47][48][note 18]

In 65 BC the Roman censor Marcus Licinius Crassus argued before the Roman Senate that Rome should annex Ptolemaic Egypt, but his proposed bill and the similar bill of tribune Servilius Rullus in 63 BC were rejected.[49][50] Ptolemy XII responded to the threat of possible annexation by offering remuneration and lavish gifts to powerful Roman statesmen, such as Pompey during his campaign against Mithridates VI of Pontus, and eventually Julius Caesar after he became Roman consul in 59 BC.[51][52][53][note 19] However, Ptolemy XII's profligate behavior bankrupted him, and he was forced to acquire loans from the Roman banker Gaius Rabirius Postumus.[54][55][56]

In 58 BC the Romans annexed Cyprus and on accusations of piracy drove Ptolemy of Cyprus, Ptolemy XII's brother, to commit suicide instead of enduring exile to Paphos.[57][58][56][note 20] Ptolemy XII remained publicly silent on the death of his brother, a decision which, along with ceding traditional Ptolemaic territory to the Romans, damaged his credibility among subjects already enraged by his economic policies.[57][59][60] Ptolemy XII was then exiled from Egypt by force, traveling first to Rhodes, then Athens, and finally the villa of triumvir Pompey in the Alban Hills, near Praeneste, Italy.[57][58][61][note 21]

Ptolemy XII spent nearly a year there on the outskirts of Rome, ostensibly accompanied by his daughter Cleopatra, then about 11.[57][61][note 22] Berenice IV sent an embassy to Rome to advocate for her rule and oppose the reinstatement of her father Ptolemy XII. Ptolemy had assassins kill the leaders of the embassy, an incident that was covered up by his powerful Roman supporters.[62][55][63][note 23] When the Roman Senate denied Ptolemy XII the offer of an armed escort and provisions for a return to Egypt, he decided to leave Rome in late 57 BC and reside at the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus.[64][65][66]

The Roman financiers of Ptolemy XII remained determined to restore him to power.[67] Pompey persuaded Aulus Gabinius, the Roman governor of Syria, to invade Egypt and restore Ptolemy XII, offering him 10,000 talents for the proposed mission.[67][68][69] Although it put him at odds with Roman law, Gabinius invaded Egypt in the spring of 55 BC by way of Hasmonean Judea, where Hyrcanus II had Antipater the Idumaean, father of Herod the Great, furnish the Roman-led army with supplies.[67][70] As a young cavalry officer, Mark Antony was under Gabinius's command.[71] He distinguished himself by preventing Ptolemy XII from massacring the inhabitants of Pelousion, and for rescuing the body of Archelaos, the husband of Berenice IV, after he was killed in battle, ensuring him a proper royal burial.[72][73] Cleopatra, then 14 years of age, would have traveled with the Roman expedition into Egypt; years later, Antony would profess that he had fallen in love with her at this time.[72][74] The Roman Republic (green) and Ptolemaic Egypt (yellow) in 40 BC

The Roman Republic (green) and Ptolemaic Egypt (yellow) in 40 BC

Gabinius was put on trial in Rome for abusing his authority, for which he was acquitted, but his second trial for accepting bribes led to his exile, from which he was recalled seven years later in 48 BC by Caesar.[75][76] Crassus replaced him as governor of Syria and extended his provincial command to Egypt, but he was killed by the Parthians at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC.[75][77] Ptolemy XII had Berenice IV and her wealthy supporters executed, seizing their properties.[78][79][80] He allowed Gabinius's largely Germanic and Gallic Roman garrison, the Gabiniani, to harass people in the streets of Alexandria and installed his longtime Roman financier Rabirius as his chief financial officer.[78][81][82][note 24]

Within a year Rabirius was placed under protective custody and sent back to Rome after his life was endangered for draining Egypt of its resources.[83][84][80][note 25] Despite these problems, Ptolemy XII created a will designating Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII as his joint heirs, oversaw major construction projects such as the Temple of Edfu and a temple at Dendera, and stabilized the economy.[85][84][86][note 26] On 31 May 52 BC, Cleopatra was made a regent of Ptolemy XII, as indicated by an inscription in the Temple of Hathor at Dendera.[87][88][89][note 27] Rabirius was unable to collect the entirety of Ptolemy XII's debt by the time of the latter's death, and so it was passed on to his successors Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII.[83][76]

Accession to the throne

Main articles: Early life of Cleopatra and Reign of Cleopatra

Left: Cleopatra dressed as a pharaoh and presenting offerings to the goddess Isis, on a limestone stele dedicated by a Greek man named Onnophris, dated 51 BC, and located in the Louvre, ParisRight: The cartouches of Cleopatra and Caesarion on a limestone stele of the High Priest of Ptah Pasherienptah III in Egypt, dated to the Ptolemaic period, and located in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Ptolemy XII died sometime before 22 March 51 BC, when Cleopatra, in her first act as queen, began her voyage to Hermonthis, near Thebes, to install a new sacred Buchis bull, worshiped as an intermediary for the god Montu in the Ancient Egyptian religion.[90][91][92][note 28] Cleopatra faced several pressing issues and emergencies shortly after taking the throne. These included famine caused by drought and a low level of the annual flooding of the Nile, and lawless behavior instigated by the Gabiniani, the now unemployed and assimilated Roman soldiers left by Gabinius to garrison Egypt.[93][94] Inheriting her father's debts, Cleopatra also owed the Roman Republic 17.5 million drachmas.[95]

In 50 BC Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, proconsul of Syria, sent his two eldest sons to Egypt, most likely to negotiate with the Gabiniani and recruit them as soldiers in the desperate defense of Syria against the Parthians.[96] The Gabiniani tortured and murdered these two, perhaps with secret encouragement by rogue senior administrators in Cleopatra's court.[96][97] Cleopatra sent the Gabiniani culprits to Bibulus as prisoners awaiting his judgment, but he sent them back to Cleopatra and chastised her for interfering in their adjudication, which was the prerogative of the Roman Senate.[98][97] Bibulus, siding with Pompey in Caesar's Civil War, failed to prevent Caesar from landing a naval fleet in Greece, which ultimately allowed Caesar to reach Egypt in pursuit of Pompey.[98]

By 29 August 51 BC, official documents started listing Cleopatra as the sole ruler, evidence that she had rejected her brother Ptolemy XIII as a co-ruler.[95][97][99] She had probably married him,[77] but there is no record of this.[90] The Ptolemaic practice of sibling marriage was introduced by Ptolemy II and his sister Arsinoe II.[100][101][102] A long-held royal Egyptian practice, it was loathed by contemporary Greeks.[100][101][102][note 29] By the reign of Cleopatra, however, it was considered a normal arrangement for Ptolemaic rulers.[100][101][102]

Despite Cleopatra's rejection of him, Ptolemy XIII still retained powerful allies, notably the eunuch Potheinos, his childhood tutor, regent, and administrator of his properties.[103][94][104] Others involved in the cabal against Cleopatra included Achillas, a prominent military commander, and Theodotus of Chios, another tutor of Ptolemy XIII.[103][105] Cleopatra seems to have attempted a short-lived alliance with her brother Ptolemy XIV, but by the autumn of 50 BC Ptolemy XIII had the upper hand in their conflict and began signing documents with his name before that of his sister, followed by the establishment of his first regnal date in 49 BC.[90][106][107][note 30]

Assassination of Pompey

Main article: Reign of Cleopatra A Roman portrait of Pompey made during the reign of Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD), a copy of an original from 70 to 60 BC, and located in the Venice National Archaeological Museum, Italy

A Roman portrait of Pompey made during the reign of Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD), a copy of an original from 70 to 60 BC, and located in the Venice National Archaeological Museum, Italy

In the summer of 49 BC, Cleopatra and her forces were still fighting against Ptolemy XIII within Alexandria when Pompey's son Gnaeus Pompeius arrived, seeking military aid on behalf of his father.[106] After returning to Italy from the wars in Gaul and crossing the Rubicon in January of 49 BC, Caesar had forced Pompey and his supporters to flee to Greece.[108][109] In perhaps their last joint decree, both Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII agreed to Gnaeus Pompeius's request and sent his father 60 ships and 500 troops, including the Gabiniani, a move that helped erase some of the debt owed to Rome.[108][110] Losing the fight against her brother, Cleopatra was then forced to flee Alexandria and withdraw to the region of Thebes.[111][112][113] By the spring of 48 BC Cleopatra had traveled to Roman Syria with her younger sister, Arsinoe IV, to gather an invasion force that would head to Egypt.[114][107][115] She returned with an army, but her advance to Alexandria was blocked by her brother's forces, including some Gabiniani mobilized to fight against her, so she camped outside Pelousion in the eastern Nile Delta.[116][107][117]

In Greece, Caesar and Pompey's forces engaged each other at the decisive Battle of Pharsalus on 9 August 48 BC, leading to the destruction of most of Pompey's army and his forced flight to Tyre, Lebanon.[116][118][119][note 31] Given his close relationship with the Ptolemies, Pompey ultimately decided that Egypt would be his place of refuge, where he could replenish his forces.[120][119][117][note 32] Ptolemy XIII's advisers, however, feared the idea of Pompey using Egypt as his base in a protracted Roman civil war.[120][121][122] In a scheme devised by Theodotus, Pompey arrived by ship near Pelousion after being invited by a written message, only to be ambushed and stabbed to death on 28 September 48 BC.[120][118][123][note 33] Ptolemy XIII believed he had demonstrated his power and simultaneously defused the situation by having Pompey's head, severed and embalmed, sent to Caesar, who arrived in Alexandria by early October and took up residence at the royal palace.[124][125][126][note 33] Caesar expressed grief and outrage over the killing of Pompey and called on both Ptolemy XIII and Cleopatra to disband their forces and reconcile with each other.[124][127][126][note 34]

Relationship with Julius Caesar

Main article: Reign of Cleopatra

Further information: Military campaigns of Julius Caesar, Siege of Alexandria (47 BC), Battle of the Nile (47 BC), and Caesareum of Alexandria The Tusculum portrait, a contemporary Roman sculpture of Julius Caesar located in the Archaeological Museum of Turin, Italy

The Tusculum portrait, a contemporary Roman sculpture of Julius Caesar located in the Archaeological Museum of Turin, Italy Cleopatra and Caesar (1866), a painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme

Cleopatra and Caesar (1866), a painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme An Egyptian portrait of a Ptolemaic queen, possibly Cleopatra, c. 51–30 BC, located in the Brooklyn Museum[128]

An Egyptian portrait of a Ptolemaic queen, possibly Cleopatra, c. 51–30 BC, located in the Brooklyn Museum[128]

Ptolemy XIII arrived at Alexandria at the head of his army, in clear defiance of Caesar's demand that he disband and leave his army before his arrival.[129][130] Cleopatra initially sent emissaries to Caesar, but upon allegedly hearing that Caesar was inclined to having affairs with royal women, she came to Alexandria to see him personally.[129][131][130] Historian Cassius Dio records that she did so without informing her brother, dressed in an attractive manner, and charmed Caesar with her wit.[129][132][133] Plutarch provides an entirely different account that alleges she was bound inside a bed sack to be smuggled into the palace to meet Caesar.[129][134][135][note 35]

When Ptolemy XIII realized that his sister was in the palace consorting directly with Caesar, he attempted to rouse the populace of Alexandria into a riot, but he was arrested by Caesar, who used his oratorical skills to calm the frenzied crowd.[136][137][138] Caesar then brought Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII before the assembly of Alexandria, where Caesar revealed the written will of Ptolemy XII—previously possessed by Pompey—naming Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII as his joint heirs.[139][137][131][note 36] Caesar then attempted to arrange for the other two siblings, Arsinoe IV and Ptolemy XIV, to rule together over Cyprus, thus removing potential rival claimants to the Egyptian throne while also appeasing the Ptolemaic subjects still bitter over the loss of Cyprus to the Romans in 58 BC.[140][137][141][note 36]

Judging that this agreement favored Cleopatra over Ptolemy XIII and that the latter's army of 20,000, including the Gabiniani, could most likely defeat Caesar's army of 4,000 unsupported troops, Potheinos decided to have Achillas lead their forces to Alexandria to attack both Caesar and Cleopatra.[140][137][142][note 37] After Caesar managed to execute Potheinos, Arsinoe IV joined forces with Achillas and was declared queen, but soon afterward had her tutor Ganymedes kill Achillas and take his position as commander of her army.[143][144][145][note 38] Ganymedes then tricked Caesar into requesting the presence of the erstwhile captive Ptolemy XIII as a negotiator, only to have him join the army of Arsinoe IV.[143][146][147] The resulting siege of the palace, with Caesar and Cleopatra trapped together inside, lasted into the following year of 47 BC.[148][127][149][note 39]

Sometime between January and March of 47 BC, Caesar's reinforcements arrived, including those led by Mithridates of Pergamon and Antipater the Idumaean.[143][127][150][note 40] Ptolemy XIII and Arsinoe IV withdrew their forces to the Nile, where Caesar attacked them. Ptolemy XIII tried to flee by boat, but it capsized, and he drowned.[151][127][152][note 41] Ganymedes may have been killed in the battle. Theodotus was found years later in Asia, by Marcus Junius Brutus, and executed. Arsinoe IV was forcefully paraded in Caesar's triumph in Rome before being exiled to the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus.[153][154][155] Cleopatra was conspicuously absent from these events and resided in the palace, most likely because she had been pregnant with Caesar's child since September 48 BC.[156][157][158]

Caesar's term as consul had expired at the end of 48 BC.[153] However, Antony, an officer of his, helped to secure Caesar's appointment as dictator lasting for a year, until October 47 BC, providing Caesar with the legal authority to settle the dynastic dispute in Egypt.[153] Wary of repeating the mistake of Cleopatra's sister Berenice IV in having a female monarch as sole ruler, Caesar appointed Cleopatra's 12-year-old brother, Ptolemy XIV, as joint ruler with the 22-year-old Cleopatra in a nominal sibling marriage, but Cleopatra continued living privately with Caesar.[159][127][150][note 42] The exact date at which Cyprus was returned to her control is not known, although she had a governor there by 42 BC.[160][150]

Caesar is alleged to have joined Cleopatra for a cruise of the Nile and sightseeing of Egyptian monuments,[127][161][162] although this may be a romantic tale reflecting later well-to-do Roman proclivities and not a real historical event.[163] The historian Suetonius provided considerable details about the voyage, including use of Thalamegos, the pleasure barge constructed by Ptolemy IV, which during his reign measured 90 metres (300 ft) in length and 24 metres (80 ft) in height and was complete with dining rooms, state rooms, holy shrines, and promenades along its two decks, resembling a floating villa.[163][164] Caesar could have had an interest in the Nile cruise owing to his fascination with geography; he was well-read in the works of Eratosthenes and Pytheas, and perhaps wanted to discover the source of the river, but turned back before reaching Ethiopia.[165][166]

Caesar departed from Egypt around April 47 BC, allegedly to confront Pharnaces II of Pontus, the son of Mithridates VI of Pontus, who was stirring up trouble for Rome in Anatolia.[167] It is possible that Caesar, married to the prominent Roman woman Calpurnia, also wanted to avoid being seen together with Cleopatra when she had their son.[167][161] He left three legions in Egypt, later increased to four, under the command of the freedman Rufio, to secure Cleopatra's tenuous position, but also perhaps to keep her activities in check.[167][168][169]

Caesarion, Cleopatra's alleged child with Caesar, was born 23 June 47 BC and was originally named "Pharaoh Caesar", as preserved on a stele at the Serapeum of Saqqara.[170][127][171][note 43] Perhaps owing to his still childless marriage with Calpurnia, Caesar remained publicly silent about Caesarion (but perhaps accepted his parentage in private).[172][note 44] Cleopatra, on the other hand, made repeated official declarations about Caesarion's parentage, naming Caesar as the father.[172][173][174]

Cleopatra and her nominal joint ruler Ptolemy XIV visited Rome sometime in late 46 BC, presumably without Caesarion, and were given lodging in Caesar's villa within the Horti Caesaris.[175][171][176][note 45] As with their father Ptolemy XII, Caesar awarded both Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIV the legal status of "friend and ally of the Roman people" (Latin: socius et amicus populi Romani), in effect client rulers loyal to Rome.[177][178][179] Cleopatra's visitors at Caesar's villa across the Tiber included the senator Cicero, who found her arrogant.[180][181] Sosigenes of Alexandria, one of the members of Cleopatra's court, aided Caesar in the calculations for the new Julian calendar, put into effect 1 January 45 BC.[182][183][184] The Temple of Venus Genetrix, established in the Forum of Caesar on 25 September 46 BC, contained a golden statue of Cleopatra (which stood there at least until the 3rd century AD), associating the mother of Caesar's child directly with the goddess Venus, mother of the Romans.[185][183][186] The statue also subtly linked the Egyptian goddess Isis with the Roman religion.[180]

Cleopatra's presence in Rome most likely had an effect on the events at the Lupercalia festival a month before Caesar's assassination.[187][188] Antony attempted to place a royal diadem on Caesar's head, but the latter refused in what was most likely a staged performance, perhaps to gauge the Roman public's mood about accepting Hellenistic-style kingship.[187][188] Cicero, who was present at the festival, mockingly asked where the diadem came from, an obvious reference to the Ptolemaic queen whom he abhorred.[187][188] Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March (15 March 44 BC), but Cleopatra stayed in Rome until about mid-April, in the vain hope of having Caesarion recognized as Caesar's heir.[189][190][191] However, Caesar's will named his grandnephew Octavian as the primary heir, and Octavian arrived in Italy around the same time Cleopatra decided to depart for Egypt.[189][190][192] A few months later, Cleopatra had Ptolemy XIV killed by poisoning, elevating her son Caesarion as her co-ruler.[193][194][174][note 46]