The danger of being too safe

The danger of being too safe

Examining our attitude towards risk Do you consider yourself to be a risk taker? Or are you very risk adverse? Does the image above of the man jumping across rocks fill you with excitement or with fear? Or perhaps a mixture of the two?

Do you consider yourself to be a risk taker? Or are you very risk adverse? Does the image above of the man jumping across rocks fill you with excitement or with fear? Or perhaps a mixture of the two?

I’d probably place myself somewhere between those two extremes, though I’m possibly nearer the risk-adverse side of the scale. In many ways I’m a pretty sensible, law-abiding, mild-mannered Englishman. I drive sensibly, wear goggles when doing DIY, and I’ve certainly never been tempted to throw myself out of an airplane.

But regardless of where you or I might typically sit relative to one another on such a scale, we are all required to make countless decisions each day and our assessment of the risks involved forms an important, if often semi-conscious, part of our decision-making process.

Yet despite all of our learning and sophistication, I’m not sure that we’re always very good at thinking intelligently about risk. I suppose, most of the time we’re simply busy and so don’t really stop to give the subject direct thought. That’s why it’s easy to default to the following train of thought:

- risk is bad

- therefore any reduction in risk is surely good

Sounds reasonable, doesn’t it? We don’t want bad stuff happening to us or to our loved ones, so surely reducing any risk is always the right thing to do.

Well, it depends.

If an effective medicine which currently causes 1 in 10,000 people to suffer an undesirable side-effect can be improved so that it’s just as effective but causes fewer people to experience the negative side-effect, then great. In such a scenario, the benefits remain and the risks are reduced. Win-win.

However, in most areas of life, things are not quite so clear-cut. School children playing conkers

School children playing conkers

There have been numerous stories in the UK press over recent years about schools stopping various common activities from continuing. Examples include preventing children from sharing out cakes they’ve baked to banning contact sports, such as rugby, from PE lessons, to ceasing outward bound activity trips. Those making such policy changes typically speak of “improving health and safety”, by which they typically mean decreasing the likelihood of anyone getting hurt (and potentially trying to sue the school, I suppose).

Along with other traditional playground games such as leapfrog and British bulldog, the game of conkers has now been banned in many schools. Now, it stands to reason that a likely consequence for such schools will be fewer pupils with knocked knuckles and scuffed knees. But, arguably, there might also be a reduction in fun, not to mention the fact that children (and adults, for that matter) learn a lot by doing; that is, that getting something slightly wrong often helps us to learn how to get it right in future.

The trouble is, when our focus is solely on the potential risks involved in an activity, we often fail to take into account the potential benefits. To put it another way, there is risk involved in trying to eliminate all risk.

A risk framework

When it comes to risk, it’s always worth considering the following aspects:

- the severity of the undesirable outcome

- the likelihood of the undesirable outcome happening

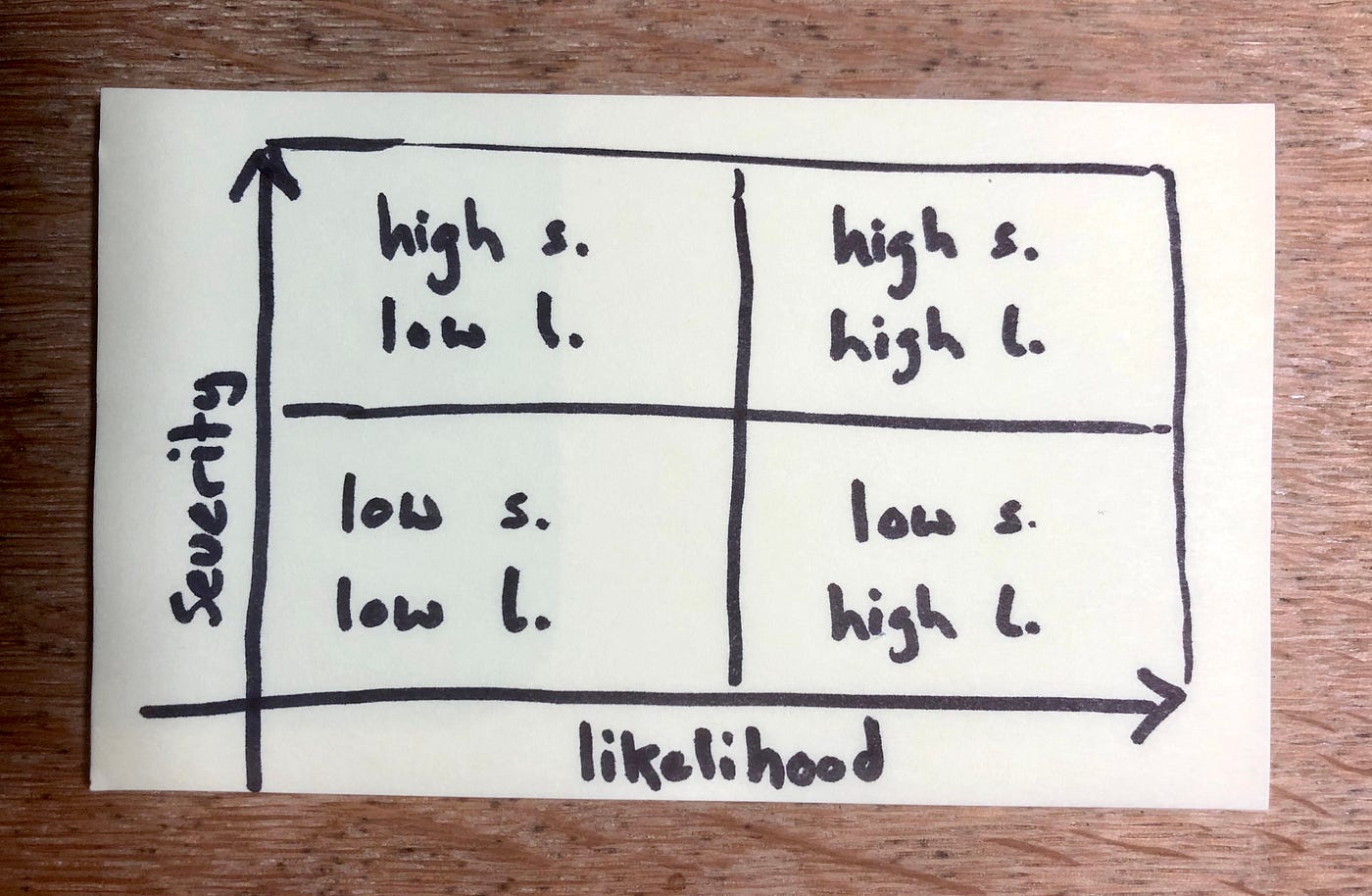

You can plot these factors on a simple four-quadrant matrix: A simple risk matrix

A simple risk matrix

high severity / low likelihood risks

- Example: the risk of dying in a commercial plane crash. (If the plane crashes, you’re unlikely to survive, but the chances of your plane crashing are infinitesimally small.)

high severity / high likelihood risks

- Example: the risk of suffering a serious or fatal injury if you play Russian roulette.

low severity / high likelihood risks

- Example: the risk of a young child getting their clothes messy if they do some painting. (They most likely will, but it probably doesn’t matter all that much and can easily be fixed afterwards by bathing the child and washing their clothes.)

low severity / low likelihood risks

- Example: the risk of getting stung by a wasp while on a walk in the countryside. (You probably won’t and even if you do, it’s not a serious matter.)

You see, whether we like it or not, almost any activity in life contains some element of risk. But, thankfully, in many cases the risks are low in both severity and likelihood, so they needn’t concern us. However, we do need to take the time to think through each scenario.

Most of my examples so far have been about risks to our physical safety. But for many of us living in modern, Western countries, our lives are actually pretty safe from physical danger most of the time. But, of course, there are other types of risk.

Risk, fear, and the myth of control

Despite many of us having incredibly safe lives, ironically we can be plagued by fear. Fear of becoming ill, fear of being involved in an accident, fear of losing our jobs. And of course the insurance industry thrives on such anxieties, offering us ever more policies that claim to be able to protect us from anything that life might throw at us. Insurance policies, safety products, security systems, etc. all appeal to our desire to try to control the world around us.

I get the attraction. But I also know that it’s a fallacy — that we never will be able to control it all. If you think about it, doing anything new, anything bold, anything worthwhile in life always involves some element of risk. Some examples:

- asking someone on a date

- marrying someone

- trying to learn a new skill

- going for a job interview

- starting a new business

- giving a talk

- sharing a piece of writing, music, or other work of art that you’ve created

Yes, there is risk involved in each of these ventures, but there is also so much that we might gain if we are but willing to take the risk. Here’s a phrase worth pondering:

Comfort and growth cannot coexist

Think about friendship for a moment. Most of us want to form deep and honest relationships with others, but this requires us to be truthful and vulnerable with others first. But if we allow others to get to know us for who are truly are, will they still like us? There’s really only one way to find out. Yet, sadly, the fear of rejection causes some to choose continued loneliness over the sometimes scary task of getting to know new people. This is a tragedy.

Am I brave? No. Not very. My life is pretty comfortable, pretty routine, pretty safe for the most part. But I do try to stay curious, to reflect on my experiences, and to remain humble enough to keep learning. I try to live my life more motivated by possibility than by fear, so I do regularly challenge myself. One example: next month I’m going to be speaking at a couple of industry conferences. Do I find such things a breeze? No. Do I have imposter syndrome on days? Yes. But I want to continue to put myself out there, to try new things, to explore, and to grow.

In conclusion

Living a full, vibrant life, being honest and vulnerable with others, and trying new things will involve risk. Yes, you might get rejected. Yes, your plan might not work. But equally, you might develop a wonderful new friendship and find that the scheme goes even better than you imagined.

Don’t just think about what might go wrong; think about what might go stupendously right too.

In these difficult times, as well as taking sensible precautions against very real risks (e.g. #WearAMask), we also need to keep on being brave and living life with confidence. We need to give ourselves the permission to step out, try new things, to fail if necessary, but to keep going and to keep learning.

A commonly used phrase in the design world is that “everything’s a prototype”. Part of what this means to me is that we don’t need to let the fear of being less than perfect stop us from even trying. In most scenarios, if we’re willing to seek and receive feedback and to keep working at things, we will be able to refine and improve upon our initial attempt — whether that be a design artifact, a new business, or a relationship.

I’ll close with some questions I’ve found useful when thinking about new opportunities:

- When presented with a new opportunity, ask yourself: why? but also ask yourself: why not?

- Ask yourself: what’s the worst that could happen? and then consider how likely this worst-case scenario actually is and how you’d respond in that worse-case scenario.

- Ask yourself: What are the risks associated with not doing this thing?

![[FAILED] Engage2Earn: Shayne is helping koalas!](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/08e2e573-f490-4ef4-93b6-f2285814da59/1)