The Bullish Case for Bitcoin

First published as a long-form article in 2018, The Bullish Case for Bitcoin has become the most read non-technical introduction to Bitcoin. An updated and significantly expanded edition of The Bullish Case for Bitcoin was published as a book in 2021 and it can now be purchased for a discounted price at my online store, along with art, clothing, and merchandise associated with the book. The foreword was written by Michael Saylor, with testimonials from Jack Dorsey (former CEO of Twitter), Cynthia Lummis (US Senator), and Adam Back (cypherpunk).

With the price of a bitcoin surging to new highs in 2017, the bullish case for investors might seem so obvious it does not need stating. Alternatively it may seem foolish to invest in a digital asset that isn’t backed by any commodity or government and whose price rise has prompted some to compare it to the tulip mania or the dot-com bubble. Neither is true; the bullish case for Bitcoin is compelling but far from obvious. There are significant risks to investing in Bitcoin, but, as I will argue, there is still an immense opportunity.

With the price of a bitcoin surging to new highs in 2017, the bullish case for investors might seem so obvious it does not need stating. Alternatively it may seem foolish to invest in a digital asset that isn’t backed by any commodity or government and whose price rise has prompted some to compare it to the tulip mania or the dot-com bubble. Neither is true; the bullish case for Bitcoin is compelling but far from obvious. There are significant risks to investing in Bitcoin, but, as I will argue, there is still an immense opportunity.

Genesis

Never in the history of the world had it been possible to transfer value between distant peoples without relying on a trusted intermediary, such as a bank or government. In 2008 Satoshi Nakamoto, whose identity is still unknown, published a 9 page solution to a long-standing problem of computer science known as the Byzantine General’s Problem. Nakamoto’s solution and the system he built from it — Bitcoin — allowed, for the first time ever, value to be quickly transferred, at great distance, in a completely trustless way. The ramifications of the creation of Bitcoin are so profound for both economics and computer science that Nakamoto should rightly be the first person to qualify for both a Nobel prize in Economics and the Turing award.

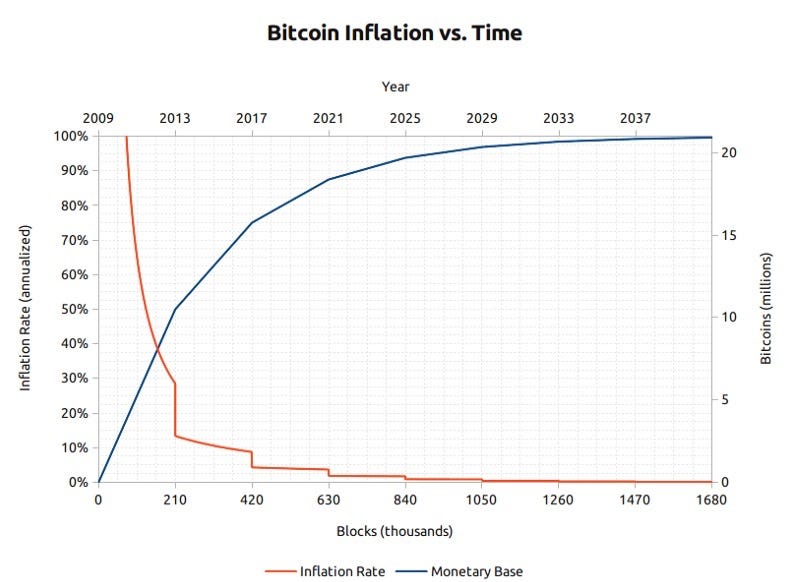

For an investor the salient fact of the invention of Bitcoin is the creation of a new scarce digital good — bitcoins. Bitcoins are transferable digital tokens that are created on the Bitcoin network in a process known as “mining”. Bitcoin mining is roughly analogous to gold mining except that production follows a designed, predictable schedule. By design, only 21 million bitcoins will ever be mined and most of these already have been — approximately 16.8 million bitcoins have been mined at the time of writing. Every four years the number of bitcoins produced by mining halves and the production of new bitcoins will end completely by the year 2140. Bitcoins are not backed by any physical commodity, nor are they guaranteed by any government or company, which raises the obvious question for a new bitcoin investor: why do they have any value at all? Unlike stocks, bonds, real-estate or even commodities such as oil and wheat, bitcoins cannot be valued using standard discounted cash flow analysis or by demand for their use in the production of higher order goods. Bitcoins fall into an entirely different category of goods, known as monetary goods, whose value is set game-theoretically. I.e., each market participant values the good based on their appraisal of whether and how much other participants will value it. To understand the game-theoretic nature of monetary goods, we need to explore the origins of money.

Bitcoins are not backed by any physical commodity, nor are they guaranteed by any government or company, which raises the obvious question for a new bitcoin investor: why do they have any value at all? Unlike stocks, bonds, real-estate or even commodities such as oil and wheat, bitcoins cannot be valued using standard discounted cash flow analysis or by demand for their use in the production of higher order goods. Bitcoins fall into an entirely different category of goods, known as monetary goods, whose value is set game-theoretically. I.e., each market participant values the good based on their appraisal of whether and how much other participants will value it. To understand the game-theoretic nature of monetary goods, we need to explore the origins of money.

The Origins of Money

In the earliest human societies, trade between groups of people occurred through barter. The incredible inefficiencies inherent to barter trade drastically limited the scale and geographical scope at which trade could occur. A major disadvantage with barter based trade is the double coincidence of wants problem. An apple grower may desire trade with a fisherman, for example, but if the fisherman does not desire apples at the same moment, the trade will not take place. Over time humans evolved a desire to hold certain collectible items for their rarity and symbolic value (examples include shells, animal teeth and flint). Indeed, as Nick Szabo argues in his brilliant essay on the origins of money, the human desire for collectibles provided a distinct evolutionary advantage for early man over his nearest biological competitors, Homo neanderthalensis.

The primary and ultimate evolutionary function of collectibles was as a medium for storing and transferring wealth.

Collectibles served as a sort of “proto-money” by making trade possible between otherwise antagonistic tribes and by allowing wealth to be transferred between generations. Trade and transfer of collectibles were quite infrequent in paleolithic societies, and these goods served more as a “store of value” rather than the “medium of exchange” role that we largely recognize modern money to play. Szabo explains:

Compared to modern money, primitive money had a very low velocity — it might be transferred only a handful of times in an average individual’s lifetime. Nevertheless, a durable collectible, what today we would call an heirloom, could persist for many generations and added substantial value at each transfer — often making the transfer even possible at all.

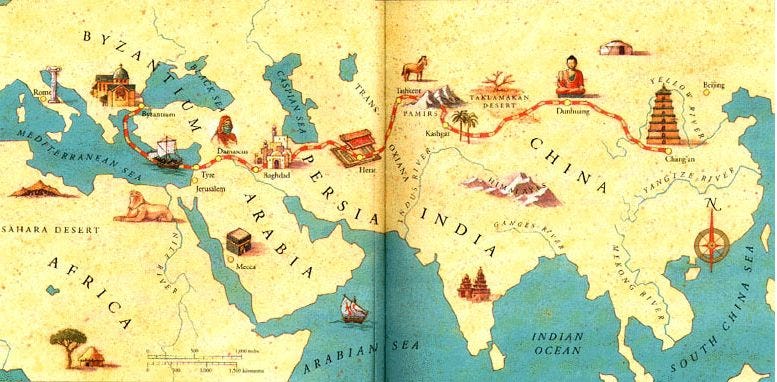

Early man faced an important game-theoretic dilemma when deciding which collectibles to gather or create: which objects would be desired by other humans? By correctly anticipating which objects might be demanded for their collectible value, a tremendous benefit was conferred on the possessor in their ability to complete trade and to acquire wealth. Some Native American tribes, such as the Narragansetts, specialized in the manufacture of otherwise useless collectibles simply for their value in trade. It is worth noting that the earlier the anticipation of future demand for a collectible good, the greater the advantage conferred to its possessor; it can be acquired more cheaply than when it is widely demanded and its trade value appreciates as the population which demands it expands. Furthermore, acquiring a good in hopes that it will be demanded as a future store of value hastens its adoption for that very purpose. This seeming circularity is actually a feedback loop that drives societies to quickly converge on a single store of value. In game-theoretic terms, this is known as a “Nash Equilibrium”. Achieving a Nash Equilibrium for a store of value is a major boon to any society, as it greatly facilitates trade and the division of labor, paving the way for the advent of civilization. Over the millennia, as human societies grew and trade routes developed, the stores of value that had emerged in individual societies came to compete against each other. Merchants and traders would face a choice of whether to save the proceeds of their trade in the store of value of their own society or the store of value of the society they were trading with, or some balance of both. The benefit of maintaining savings in a foreign store of value was the enhanced ability to complete trade in the associated foreign society. Merchants holding savings in a foreign store of value also had an incentive to encourage its adoption within their own society, as this would increase the purchasing power of their savings. The benefits of an imported store of value accrued not only to the merchants doing the importing, but also to the societies themselves. Two societies converging on a single store of value would see a substantial decrease in the cost of completing trade with each other and an attendant increase in trade-based wealth. Indeed, the 19th century was the first time when most of the world converged on a single store of value — gold — and this period saw the greatest explosion of trade in the history of the world. Of this halcyon period, Lord Keynes wrote:

Over the millennia, as human societies grew and trade routes developed, the stores of value that had emerged in individual societies came to compete against each other. Merchants and traders would face a choice of whether to save the proceeds of their trade in the store of value of their own society or the store of value of the society they were trading with, or some balance of both. The benefit of maintaining savings in a foreign store of value was the enhanced ability to complete trade in the associated foreign society. Merchants holding savings in a foreign store of value also had an incentive to encourage its adoption within their own society, as this would increase the purchasing power of their savings. The benefits of an imported store of value accrued not only to the merchants doing the importing, but also to the societies themselves. Two societies converging on a single store of value would see a substantial decrease in the cost of completing trade with each other and an attendant increase in trade-based wealth. Indeed, the 19th century was the first time when most of the world converged on a single store of value — gold — and this period saw the greatest explosion of trade in the history of the world. Of this halcyon period, Lord Keynes wrote:

What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man that age was … for any man of capacity or character at all exceeding the average, into the middle and upper classes, for whom life offered, at a low cost and with the least trouble, conveniences, comforts, and amenities beyond the compass of the richest and most powerful monarchs of other ages. The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep

The attributes of a good store of value

When stores of value compete against each other, it is the specific attributes that make a good store of value that allows one to out-compete another at the margin and increase demand for it over time. While many goods have been used as stores of value or “proto-money”, certain attributes emerged that were particularly demanded and allowed goods with these attributes to out-compete others. An ideal store of value will be:

- Durable: the good must not be perishable or easily destroyed. Thus wheat is not an ideal store of value

- Portable: the good must be easy to transport and store, making it possible to secure it against loss or theft and allowing it to facilitate long-distance trade. A cow is thus less ideal than a gold bracelet.

- Fungible: one specimen of the good should be interchangeable with another of equal quantity. Without fungibility, the coincidence of wants problem remains unsolved. Thus gold is better than diamonds, which are irregular in shape and quality.

- Verifiable: the good must be easy to quickly identify and verify as authentic. Easy verification increases the confidence of its recipient in trade and increases the likelihood a trade will be consummated.

- Divisible: the good must be easy to subdivide. While this attribute was less important in early societies where trade was infrequent, it became more important as trade flourished and the quantities exchanged became smaller and more precise.

- Scarce: As Nick Szabo termed it, a monetary good must have “unforgeable costliness”. In other words, the good must not be abundant or easy to either obtain or produce in quantity. Scarcity is perhaps the most important attribute of a store of value as it taps into the innate human desire to collect that which is rare. It is the source of the original value of the store of value.

- Established history: the longer the good is perceived to have been valuable by society, the greater its appeal as a store of value. A long-established store of value will be hard to displace by a new upstart except by force of conquest or if the arriviste is endowed with a significant advantage among the other attributes listed above.

- Censorship-resistant: a new attribute, which has become increasingly important in our modern, digital society with pervasive surveillance, is censorship-resistance. That is, how difficult is it for an external party such as a corporation or state to prevent the owner of the good from keeping and using it. Goods that are censorship-resistant are ideal to those living under regimes that are trying to enforce capital controls or to outlaw various forms of peaceful trade.

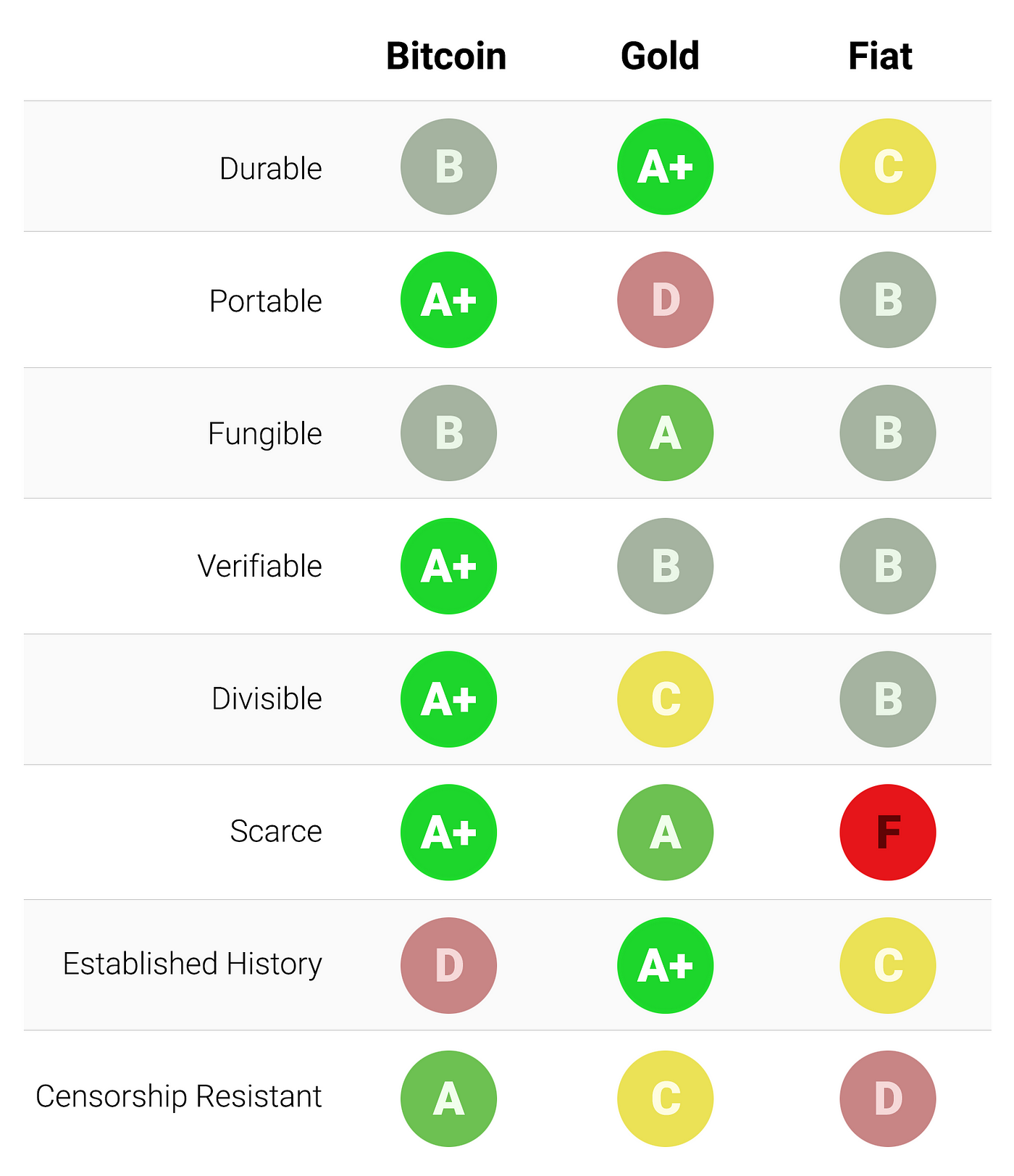

The table below grades Bitcoin, gold and fiat money (such as dollars) against the attributes listed above and is followed by an explanation of each grade:

Durability:

Gold is the undisputed King of durability. The vast majority of gold that has ever been mined or minted, including the gold of the Pharaohs, remains extant today and will likely be available a thousand years hence. Gold coins that were used as money in antiquity still maintain significant value today. Fiat currency and bitcoins are fundamentally digital records that may take physical form (such as paper bills). Thus it is not their physical manifestation whose durability should be considered (since a tattered dollar bill may be exchanged for a new one), but the durability of the institution that issues them. In the case of fiat currencies, many governments have come and gone over the centuries, and their currencies disappeared with them. The Papiermark, Rentenmark and Reichsmark of the Weimar Republic no longer have value because the institution that issued them no longer exists. If history is a guide, it would be folly to consider fiat currencies durable in the long term — the US dollar and British Pound are relative anomalies in this regard. Bitcoins, having no issuing authority, may be considered durable so long as the network that secures them remains in place. Given that Bitcoin is still in its infancy, it is too early to draw strong conclusions about its durability. However, there are encouraging signs that, despite prominent instances of nation-states attempting to regulate Bitcoin and years of attacks by hackers, the network has continued to function, displaying a remarkable degree of “anti-fragility”.

Portability:

Bitcoins are the most portable store of value ever used by man. Private keys representing hundreds of millions of dollars can be stored on a tiny USB drive and easily carried anywhere. Furthermore, equally valuable sums can be transmitted between people on opposite ends of the earth near instantly. Fiat currencies, being fundamentally digital, are also highly portable. However, government regulations and capital controls mean that large transfers of value usually take days or may not be possible at all. Cash can be used to avoid capital controls, but then the risk of storage and cost of transportation become significant. Gold, being physical in form and incredibly dense, is by far the least portable. It is no wonder that the majority of bullion is never transported. When bullion is transferred between a buyer and a seller it is typically only the title to the gold that is transferred, not the physical bullion itself. Transmitting physical gold across large distances is costly, risky and time-consuming.

Fungibility:

Gold provides the standard for fungibility. When melted down, an ounce of gold is essentially indistinguishable from any other ounce, and gold has always traded this way on the market. Fiat currencies, on the other hand, are only as fungible as the issuing institutions allow them to be. While it may be the case that a fiat banknote is usually treated like any other by merchants accepting them, there are instances where large-denomination notes have been treated differently to small ones. For instance, India’s government, in an attempt to stamp out India’s untaxed gray market, completely demonetized their 500 and 1000 rupee banknotes. The demonetization caused 500 and 1000 rupee notes to trade at a discount to their face value, making them no longer truly fungible with their lower denomination sibling notes. Bitcoins are fungible at the network level, meaning that every bitcoin, when transmitted, is treated the same on the Bitcoin network. However, because bitcoins are traceable on the blockchain, a particular bitcoin may become tainted by its use in illicit trade and merchants or exchanges may be compelled not to accept such tainted bitcoins. Without improvements to the privacy and anonymity of Bitcoin’s network protocol, bitcoins cannot be considered as fungible as gold.

Verifiability:

For most intents and purposes, both fiat currencies and gold are fairly easy to verify for authenticity. However, despite providing features on their banknotes to prevent counterfeiting, nation-states and their citizens still face the potential to be duped by counterfeit bills. Gold is also not immune from being counterfeited. Sophisticated criminals have used gold-plated tungsten as a way of fooling gold investors into paying for false gold. Bitcoins, on the other hand, can be verified with mathematical certainty. Using cryptographic signatures, the owner of a bitcoin can publicly prove she owns the bitcoins she says she does.

Divisibility:

Bitcoins can be divided down to a hundred millionth of a bitcoin and transmitted at such infinitesimal amounts (network fees can, however, make transmission of tiny amounts uneconomic). Fiat currencies are typically divisible down to pocket change, which has little purchasing power, making fiat divisible enough in practice. Gold, while physically divisible, becomes difficult to use when divided into small enough quantities that it could be useful for lower-value day-to-day trade.

Scarcity:

The attribute that most clearly distinguishes Bitcoin from fiat currencies and gold is its predetermined scarcity. By design, at most 21 million bitcoins can ever be created. This gives the owner of bitcoins a known percentage of the total possible supply. For instance, an owner of 10 bitcoins would know that at most 2.1 million people on earth (less than 0.03% of the world’s population) could ever have as many bitcoins as they had. Gold, while remaining quite scarce through history, is not immune to increases in supply. If it were ever the case that a new method of mining or acquiring gold became economic, the supply of gold could rise dramatically (examples include sea-floor or asteroid mining). Finally, fiat currencies, while only a relatively recent invention of history, have proven to be prone to constant increases in supply. Nation-states have shown a persistent proclivity to inflate their money supply to solve short-term political problems. The inflationary tendencies of governments across the world leave the owner of a fiat currency with the likelihood that their savings will diminish in value over time.

Established history:

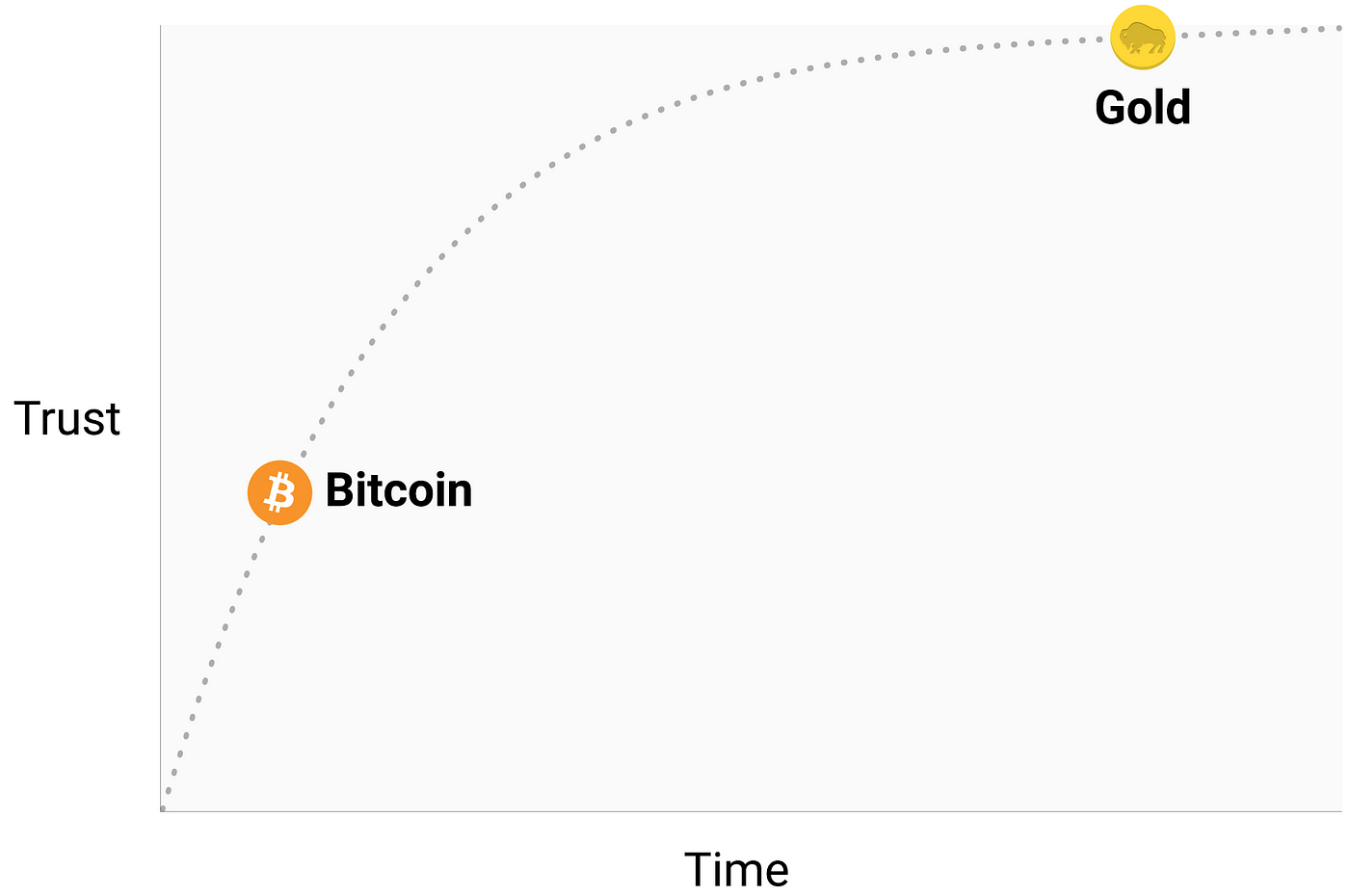

No monetary good has a history as long and storied as gold, which has been valued for as long as human civilization has existed. Coins minted in the distant days of antiquity still maintain significant value today. The same cannot be said of fiat currencies, which are a relatively recent anomaly of history. From their inception, fiat currencies have had a near-universal tendency toward eventual worthlessness. The use of inflation as an insidious means of invisibly taxing a citizenry has been a temptation that few states in history have been able to resist. If the 20th century, in which fiat monies came to dominate the global monetary order, established any economic truth, it is that fiat money cannot be trusted to maintain its value over the long or even medium term. Bitcoin, despite its short existence, has weathered enough trials in the market that there is a high likelihood it will not vanish as a valued asset any time soon. Furthermore, the Lindy effect suggests that the longer Bitcoin remains in existence the greater society’s confidence that it will continue to exist long into the future. In other words, the societal trust of a new monetary good is asymptotic in nature, as is illustrated in the graph below: If Bitcoin exists for 20 years, there will be near-universal confidence that it will be available forever, much as people believe the Internet is a permanent feature of the modern world.

If Bitcoin exists for 20 years, there will be near-universal confidence that it will be available forever, much as people believe the Internet is a permanent feature of the modern world.

Censorship resistance:

One of the most significant sources of early demand for bitcoins was their use in the illicit drug trade. Many subsequently surmised, mistakenly, that the primary demand for bitcoins was due to their ostensible anonymity. Bitcoin, however, is far from an anonymous currency; every transaction transmitted on the Bitcoin network is forever recorded on a public blockchain. The historical record of transactions allows for later forensic analysis to identify the source of a flow of funds. It was such an analysis that led to the apprehending of a perpetrator of the infamous MtGox heist. While it is true that a sufficiently careful and diligent person can conceal their identity when using Bitcoin, this is not why Bitcoin was so popular for trading drugs. The key attribute that makes Bitcoin valuable for proscribed activities is that it is “permissionless” at the network level. When bitcoins are transmitted on the Bitcoin network, there is no human intervention deciding whether the transaction should be allowed. As a distributed peer-to-peer network, Bitcoin is, by its very nature, designed to be censorship-resistant. This is in stark contrast to the fiat banking system, where states regulate banks and the other gatekeepers of money transmission to report and prevent outlawed uses of monetary goods. A classic example of regulated money transmission is capital controls. A wealthy millionaire, for instance, may find it very hard to transfer their wealth to a new domicile if they wish to flee an oppressive regime. Although gold is not issued by states, its physical nature makes it difficult to transmit at distance, making it far more susceptible to state regulation than Bitcoin. India’s Gold Control Act is an example of such regulation.

Bitcoin excels across the majority of attributes listed above, allowing it to outcompete modern and ancient monetary goods at the margin and providing a strong incentive for its increasing adoption. In particular, the potent combination of censorship resistance and absolute scarcity has been a powerful motivator for wealthy investors to allocate a portion of their wealth to the nascent asset class.

The Evolution of Money

There is an obsession in modern monetary economics with the medium of exchange role of money. In the 20th century, states have monopolized the issuance of money and continually undermined its use as a store of value, creating a false belief that money is primarily defined as a medium of exchange. Many have criticized Bitcoin as being an unsuitable money because its price has been too volatile to be suitable as a medium of exchange. This puts the cart before the horse, however. Money has always evolved in stages, with the store of value role preceding the medium of exchange role. One of the fathers of marginalist economics, William Stanley Jevons, explained that:

Historically speaking … gold seems to have served, firstly, as a commodity valuable for ornamental purposes; secondly, as stored wealth; thirdly, as a medium of exchange; and, lastly, as a measure of value.

Using modern terminology, money always evolves in the following four stages:

- Collectible: In the very first stage of its evolution, money will be demanded solely based on its peculiar properties, usually becoming a whimsy of its possessor. Shells, beads and gold were all collectibles before later transitioning to the more familiar roles of money.

- Store of value: Once it is demanded by enough people for its peculiarities, money will be recognized as a means of keeping and storing value over time. As a good becomes more widely recognized as a suitable store of value, its purchasing power will rise as more people demand it for this purpose. The purchasing power of a store of value will eventually plateau when it is widely held and the influx of new people desiring it as a store of value dwindles.

- Medium of exchange: When money is fully established as a store of value, its purchasing power will stabilize. Having stabilized in purchasing power, the opportunity cost of using money to complete trades will diminish to a level where it is suitable for use as a medium of exchange. In the earliest days of Bitcoin, many people did not appreciate the huge opportunity cost of using bitcoins as a medium of exchange, rather than as an incipient store of value. The famous story of a man trading 10,000 bitcoins (worth approximately $94 million at the time of this article’s writing) for two pizzas illustrates this confusion.

- Unit of account: When money is widely used as a medium of exchange, goods will be priced in terms of it. I.e., the exchange ratio against money will be available for most goods. It is a common misconception that bitcoin prices are available for many goods today. For example, while a cup of coffee might be available for purchase using bitcoins, the price listed is not a true bitcoin price; rather it is the dollar price desired by the merchant translated into bitcoin terms at the current USD/BTC market exchange rate. If the price of bitcoin were to drop in dollar terms, the number of bitcoins requested by the merchant would increase commensurately. Only when merchants are willing to accept bitcoins for payment without regard to the bitcoin exchange rate against fiat currencies can we truly think of Bitcoin as having become a unit of account.

Monetary goods that are not yet a unit of account may be thought of as being “partly monetized”. Today gold fills such a role, being a store of value but having been stripped of its medium of exchange and unit of account roles by government intervention. It is also possible that one good fills the medium of exchange role of money while another good fills the other roles. This is typically true in countries with dysfunctional states, such as Argentina or Zimbabwe. In his book Digital Gold, Nathaniel Popper writes:

In America, the dollar seamlessly serves the three functions of money: providing a medium of exchange, a unit for measuring the cost of goods, and an asset where value can be stored. In Argentina, on the other hand, while the peso was used as a medium of exchange — for daily purchases — no one used it as a store of value. Keeping savings in the peso was equivalent to throwing away money. So people exchanged any pesos they wanted to save for dollars, which kept their value better than the peso. Because the peso was so volatile, people usually remembered prices in dollars, which provided a more reliable unit of measure over time.

Bitcoin is currently transitioning from the first stage of monetization to the second stage. It will likely be several years before Bitcoin transitions from being an incipient store of value to being a true medium of exchange, and the path it takes to get there is still fraught with risk and uncertainty. It is striking to note that the same transition took many centuries for gold. No one alive has seen the real-time monetization of a good (as is taking place with Bitcoin), so there is precious little experience regarding the path this monetization will take.

Path dependence

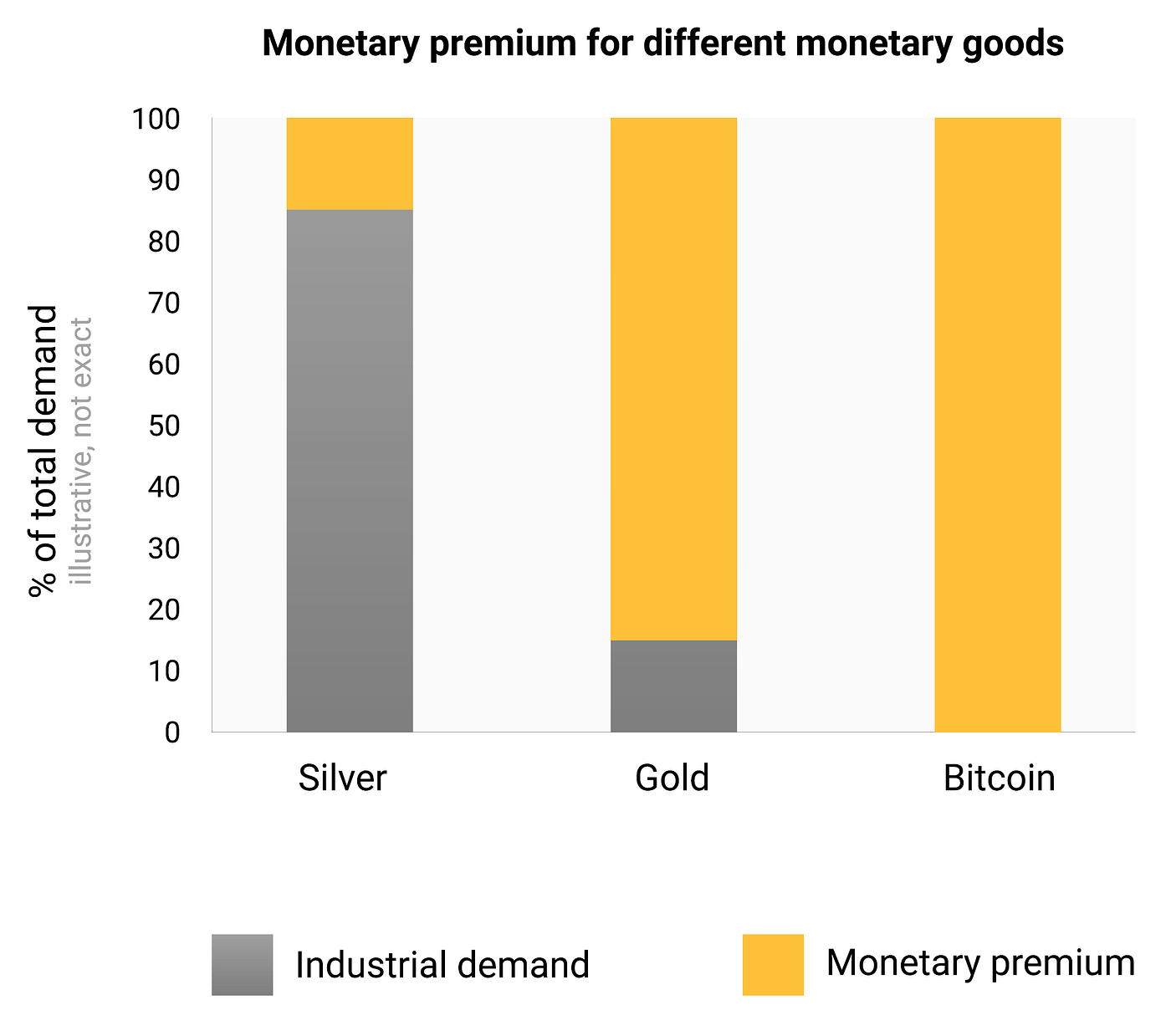

In the process of being monetized, a monetary good will soar in purchasing power. Many have commented that the increase in purchasing power of Bitcoin creates the appearance of a “bubble”. While this term is often using disparagingly to suggest that Bitcoin is grossly overvalued, it is unintentionally apt. A characteristic that is common to all monetary goods is that their purchasing power is higher than can be justified by their use-value alone. Indeed, many historical monies had no use-value at all. The difference between the purchasing power of a monetary good and the exchange-value it could command for its inherent usefulness can be thought of as a “monetary premium”. As a monetary good transitions through the stages of monetization (listed in the section above), the monetary premium will increase. The premium does not, however, move in a straight, predictable line. A good X that was in the process of being monetized may be outcompeted by another good Y that is more suitable as money, and the monetary premium of X may drop or vanish entirely. The monetary premium of silver disappeared almost entirely in the late 19th century when governments across the world largely abandoned it as money in favor of gold. Even in the absence of exogenous factors such as government intervention or competition from other monetary goods, the monetary premium for a new money will not follow a predictable path. Economist Larry White observed that:

Even in the absence of exogenous factors such as government intervention or competition from other monetary goods, the monetary premium for a new money will not follow a predictable path. Economist Larry White observed that:

the trouble with [the] bubble story, of course, is that [it] is consistent with any price path, and thus gives no explanation for a particular price path

The process of monetization is game-theoretic; every market participant attempts to anticipate the aggregate demand of other participants and thereby the future monetary premium. Because the monetary premium is unanchored to any inherent usefulness, market participants tend to default to past prices when determining whether a monetary good is cheap or expensive and whether to buy or sell it. The connection of current demand to past prices is known as “path dependence” and is perhaps the greatest source of confusion in understanding the price movements of monetary goods.

When the purchasing power of a monetary good increases with increasing adoption, market expectations of what constitutes “cheap” and “expensive” shift accordingly. Similarly, when the price of a monetary good crashes, expectations can switch to a general belief that prior prices were “irrational” or overly inflated. The path dependence of money is illustrated by the words of well-known Wall Street fund manager Josh Brown:

I bought [bitcoins] at like $2300 and had an immediate double on my hands. Then I started saying “I can’t buy more of it,” as it rose, even though that’s an anchored opinion based on nothing other than the price where I originally got it. Then, as it fell over the last week because of a Chinese crackdown on the exchanges, I started saying to myself, “Oh good, I hope it gets killed so I can buy more.”

The truth is that the notions of “cheap” and “expensive” are essentially meaningless in reference to monetary goods. The price of a monetary good is not a reflection of its cash flow or how useful it is but, rather, is a measure of how widely adopted it has become for the various roles of money.

Further complicating the path-dependent nature of money is the fact that market participants do not merely act as dispassionate observers, trying to buy or sell in anticipation of future movements of the monetary premium, but also act as active evangelizers. Since there is no objectively correct monetary premium, proselytizing the superior attributes of a monetary good is more effective than for regular goods, whose value is ultimately anchored to cash flow or use-demand. The religious fervor of participants in the Bitcoin market can be observed in various online forums where owners actively promote the benefits of Bitcoin and the wealth that can be made by investing in it.

While the comparison to religion may give Bitcoin an aura of irrational faith, it is entirely rational for the individual owner to evangelize for a superior monetary good and for society as a whole to standardize on it. Money acts as the foundation for all trade and savings, so the adoption of a superior form of money has tremendous multiplicative benefits to wealth creation for all members of a society.

![[FAILED] Engage2Earn: McEwen boost for Rob Mitchell](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/c798d46f-d3b8-4a66-bf48-7e1ef50b4338/1)

![[ℕ𝕖𝕧𝕖𝕣] 𝕊𝕖𝕝𝕝 𝕐𝕠𝕦𝕣 𝔹𝕚𝕥𝕔𝕠𝕚𝕟 - Is Trump Dying? Or Only Killing The Market?](https://cdn.bulbapp.io/frontend/images/a129e75e-4fa1-46cc-80b6-04e638877e46/1)